The scars of school never entirely heal, do they? It’s been almost 20 years since I attended an institution of higher learning, or any kind of learning, but the onset of the U.S. Open always calls up that swirling, oppressive mix of early fall emotions that came with the annual return to class. The dwindling light and the first sporadic cool breezes of late August still bring back a taste of the anticipation and dread that came with school, its girls, books, teachers, sweaters, and bus rides. Wimbledon happened at the early height of summer, and as a kid its pure green was the perfect accompaniment to our escape. The Open felt heavier. Grades were back; life was back; the future was back. You felt the pressure of all three. The party, the free ride, was over.

I wrote about the 1981 U.S. Open here the other day, and seeing clips of the final brought back an intense set of memories of that particular fall, when I was 12. I watched that tournament—which I think was televised only on the weekends—mostly on two tiny (like 10 inches each) TVs, one in my family’s kitchen and the other in the basement of my friend Tom's house. I’d played tennis seriously for a few years, and I was all about Bjorn Borg. When he played, I sat without moving or speaking, with my back pinned against the couch. During his 1979 Wimbledon final against Roscoe Tanner, I was next to my uncle, who was rooting for Tanner. When the match got tight at the end of the fifth set, he put his hand on my stomach jokingly, as if to say, “Getting nervous?” I threw his hand off angrily and turned the other way.

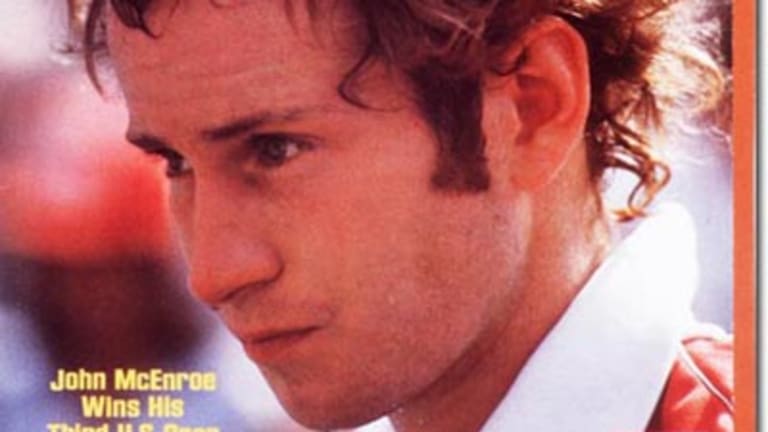

To me McEnroe was the invader, the interloper—how could anyone think this kid should steal the king’s crown? Well, my friend Tom did. He had just picked up the sport that summer, and had no special reverence for Borg. He was pro-American, in the new Reaganite spirit of nationalism that had swept the country since the president’s shooting that spring. McEnroe was the tennis equivalent of that spirit. America was back, and the Davis Cup stalwart was doing his part on the court. His serve-and-volley style seemed to be a return to the manly tennis values of an earlier day. He attacked, unlike Borg. He revered Laver. Jack Kramer loved him. While I would root for him him too someday, I couldn't do that with Borg around.

Tom and I were starting 7th grade that fall, a new junior high school that was bigger than the one we had attended. We spent the last weekend before venturing into that massive unknown watching the Open in his basement. Along with McEnroe, there was also a sense at that point, three years after the tournament had moved from the grass and clay of Forest Hills to the hot asphalt of Flushing Meadows, that the Open had shed its image as Wimbledon's poorly maintained cousin. The site was modern, it was bigger, the event was more lucrative. It was the future. Just as important, for the first time in tennis history, it was the Open, rather than Wimbledon, that felt like the true world championship of tennis. Instead of grass, the bumpy and slippery surface of the old private club, the Open was played on the same true-bouncing hard courts that so many new players had learned the game on over the last decade. Plus, McEnroe, who had won the tournament the previous two years, was returning to New York in 1981 as the No. 1 seed and the new Wimbledon champion. Borg had never won at the Open, on the courts that now were the game's new surface of record.

This sense of the increased stature of the Open only increased the pressure I felt watching it. I could feel it all the way from New York in the town where we lived. Borg had to win it; something would be incomplete in the universe until he did. McEnroe couldn’t actually get the better of him, could he? The Red Sox would never beat the Yankees, right? That Labor Day weekend, the middle of the tournament, Tom and I hit balls in the mornings at the courts at our old elementary school, and then watched as McEnroe and Borg slowly descended through the brackets and made their way toward each other from opposite ends of the draw. We watched a tight first set between McEnroe and Kevin Curren. At one point, Tom said, “Curren’s good, but he’s got no forehand.” Naturally, on the next point Curren went on a forehand rampage, hitting four or five of them in a row that pushed McEnroe farther back, before finishing it with one last forehand winner. Tom and I couldn’t believe it. We couldn’t stop laughing.

But the tension between us was real. He hated the “arrogant” Borg, even calling him a “cur,” which I simply could not comprehend. What was there not to like about Borg? He had aura. He showed that being aggressive didn’t always work, that quietness and class, as well as a devastatingly pinpoint passing shot, were life’s real truths. To Tom, Mac was the return of some kind of retro world order that we’d both heard lamented by our parents so often in the late 70s. He played the game the right way, up front, with authority and initiative.

We watched McEnroe play a see-saw semifinal with his friend Vitas Gerulaitis. I prayed Vitas would pull out the fifth set; Borg had never lost to him! But that would have gone against all the laws of destiny. At the end, when McEnroe finally finished it, Tom bent over and pumped his fist. I was silent, hating Vitas for losing, wishing it could all be played over again. Later that night, though, I was encouraged, in a bittersweet way, by Borg’s demolition of Jimmy Connors in the other semi, in one of the finest matches of his career. I’d sat through two Open finals between these two where Connors had spoiled Borg’s chances to get the New York monkey off his back. Connors was that monkey, really, but even now, when Borg had finally beaten him here, it wasn’t enough. It would be the last match Borg would win at a Grand Slam.

The morning of the final, I could feel my legs shake when I got up. This match begins at 4:00 because of the NFL, and the fact that it goes from daylight to darkness isn’t easy for the players. But there’s something about that time, and that twilight, that maximizes the pressure and jittery energy of the moment, at least as a fan. You’ve had just a little longer to think about it than a normal day match, but it doesn’t have the relaxed, end-of-day atmosphere of a night match, either. The Open men's final makes dusk seem vicious.

This was it. If Borg lost . . . it was the abyss. No U.S. Open and three straight Slam losses to McEnroe. It was unthinkable. I couldn’t take watching the match with Tom, so I sat by myself in my family’s kitchen and saw it on an even tinier black-and-white set. It was the same TV that had brought us so much good luck the previous year when the Phillies had won the World Series. Not this time: I sat on a kitchen chair with my knee in my mouth—funny how good it tastes, isn’t it?—and watched as McEnroe gutted Borg with two topspin lobs late in the third set. I can still feel the awful sinking helpless feeling I had as I saw those shots go up and come down, way inside the lines and far out of Borg’s reach.

I yelled at my mom for something, and then watched in stone cold silence as the crowd booed Borg’s early departure from the trophy ceremony. Even McEnroe didn’t seem to fully enjoy himself. He closed his remarks saying, with an odd bitterness of his own, that he hoped Borg would "win this damn tournament someday.”

It was a joyless ending to a now legendary era in tennis. The next year, with Borg gone, I became a huge McEnroe fan and remained one for the rest of his career. Tom quit tennis that same year. We stayed best friends all the way through high school. Every year, as school began and all the anticipation and dread, the books and girls, filled our heads once again, we headed to his basement to watch the Open. Thank God it was never like '81 again.