This morning I woke up a little early and went straight to my favorite stream-gathering website. This isn't unusual during a big tournament, but today I bypassed the tennis listings and headed to that hodgepodge of mostly un-American activities called the “Other Sports” page. Snooker, darts, figure skating, squash: Anything thought to be on the fringes of the mainstream gets tossed in here. Somehow, despite its hundreds of millions of rabid fans, that also includes cricket.

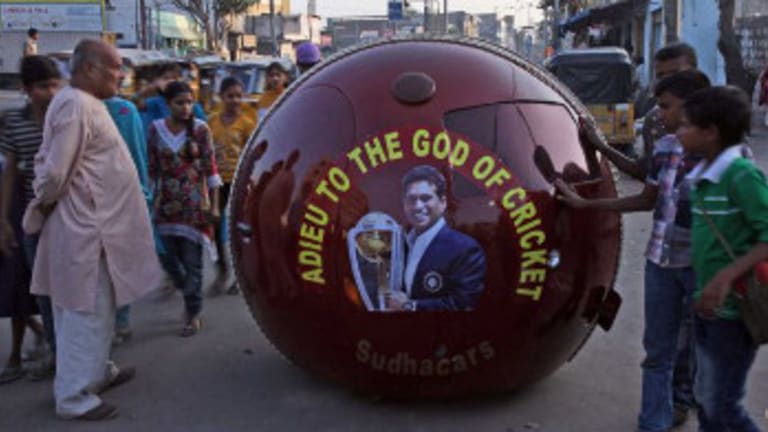

I had woken up early because, from what I had read over the last few days, this would be my last chance to see the greatest cricketer of his generation, India’s Sachin Tendulkar. He had announced that after 24 years, the test match between India and the West Indies, which began Thursday in Mumbai, would be his last. I had never seen Tendulkar bat. I had never even heard his name until two years ago, when, at age 38, he helped his country to its first World Cup title in a generation. Even then, “Tendulkar” was a mythic figure rather than a real person to me. His name would pop up on Twitter, or be passed around in conversations among Aussie and British journalists at tennis tournaments. What did he look like? Was he retired or still playing? I didn’t know.

I wasn’t the only one. As a character in Joseph O’Neill’s novel, Netherland, says, “There is a limit to what Americans can see or understand, and the limit is cricket.” As O’Neill himself said in an interview, cricket is a “classic symbol of the un-American.” Like most of us in the States, I’ve never understood the rules, and there are enough foreign terms involved to make it feel like the sport's commentators are speaking another language—just typing “test match” and “bat” above felt a little risky, as if I were writing in French. I’d like to understand cricket: C.L.R. James and Simon Barnes have both assured me that the sport is a “complex metaphor for all of life,” and I trust them. But it's a daunting task when you don’t even know what an “over” is.

It’s also tough when you never see the sport played. This morning, I woke up too late to see Tendulkar; a Google search revealed that he had been “dismissed for 74.” As one journalist put it, “Just as expectations were rising for his 101st international century, Tendulkar knicked a delivery to the West Indies skipper to leave Mumbai’s Wankhede Stadium crowd in stunned silence. Tendulkar walked off with his bat raised to a standing ovation.”

That sounds like a fitting exit, but for some, it seems, it comes a couple of years too late. In yesterday’s New York Times, Tunku Varadarajan wrote an article entitled “Where the Gods Live On...and On,” in which he said that Tendulkar should have hung up his bat after the 2011 World Cup triumph, or maybe even before. Varadarajan tries to explain what Tendulkar means to India. “Think of him as a cross between Babe Ruth and Martin Luther King,” he writes, describing Tendulkar as a symbol of the country’s growth over the last two decades, a prodigy who made good on all of his talent yet remained humble and self-effacing, a team player at heart. Varadarajan also explains why he believes Tendulkar stayed too long, to the point where his skills have seriously eroded: He meant too much to his country.