The Arthur and Arthur Show: Ashe, Collins and the 1968 US Open

By Steve Tignor Aug 26, 2018The Tennis Conversation: Tim Henman

By Matt Fitzgerald May 21, 2021Debating best-of-three sets vs. best-of-five

By Steve Tignor May 21, 2021The Pick: Lorenzo Musetti vs. Sebastian Korda, ATP Lyon second round

By Cale Hammond May 18, 2021In Geneva, Roger Federer loses clay-court comeback to Pablo Andujar

By John Berkok May 18, 2021The Pick: Jannik Sinner vs. Aslan Karatsev, ATP Lyon first round

By Cale Hammond May 17, 2021Officials deny that 2022 Australian Open could move

By Kamakshi Tandon May 17, 2021Week in Preview: Serena, Federer lead stars tuning up for French Open

By Steve Tignor May 17, 2021Nadal finds the final answer for Djokovic in roller coaster Rome final

By Steve Tignor May 16, 2021Rafael Nadal battles past Novak Djokovic to win Rome for 10th time

By John Berkok May 16, 2021The Arthur and Arthur Show: Ashe, Collins and the 1968 US Open

Published Aug 26, 2018

Advertising

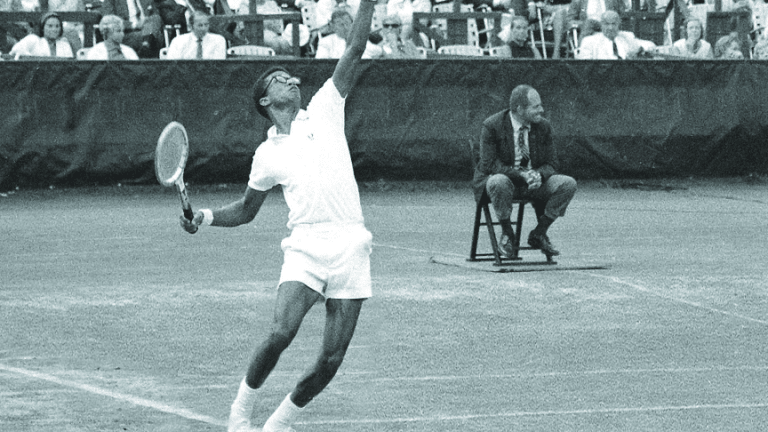

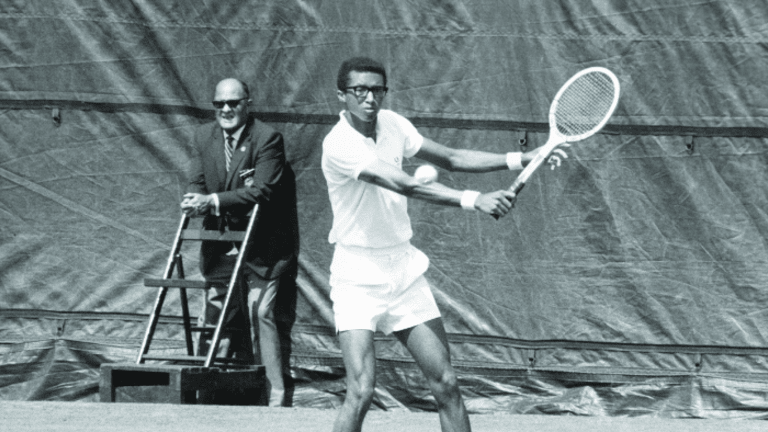

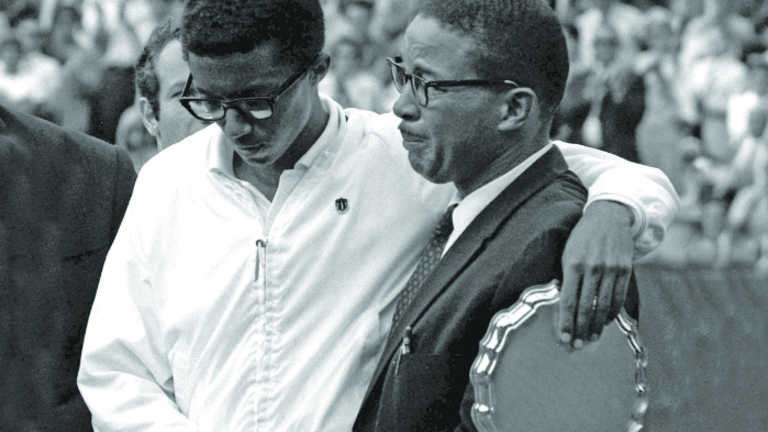

The two Arthurs sat in a broadcast booth high above Longwood Cricket Club and talked. One of them, Arthur Robert Ashe, Jr., was a bespectacled, 25-year-old African-American who had just won the National Amateur championship. The other, Arthur Worth “Bud” Collins, Jr., was a 39-year-old reporter who had just made his national debut as a TV commentator. Each was in the midst of a long-awaited professional breakthrough. This being the summer of 1968, so was the sport they loved.

Their conversation went out over WGBH, Boston’s public TV station. With no commercial constraints, Ashe and Collins talked at length about race relations in the U.S., the future of South Africa, and what it was like for Ashe to play at clubs that wouldn’t admit him as a member.

“I hope I see changes,” Ashe said.

Change was everywhere in 1968, and it was even coming to tennis. The following week, the USLTA would welcome professionals to Forest Hills for the first time. Unable to let go of its history entirely, though, the governing body, as Collins put it, “conducted a contrived carnival for that transitional year”—the U.S. Amateur Championships, at Longwood.

The event was split between past and future. It was staged at an old-line private club, yet it was the first major U.S. tennis tournament to be broadcast in color. Because of that, it was also the first to allow non-white clothing. For his semifinal, Ashe daringly donned a “trophy yellow” shirt.

The two Arthurs each personified this progressive-conservative blend. Ashe became the first African-American man to win a national championship, but he was also a clean-cut Army Lieutenant who had declined to turn pro. And while Collins, with his bow ties, loud pants and gift of gab, would personify the preppy side of tennis for many, he was a serious journalist committed to progress.

Ashe and Collins came a long way to get to Longwood, but neither knew how far he would travel over the next three weeks.

The Arthur and Arthur Show: Ashe, Collins and the 1968 US Open

Advertising

Growing up in tiny Berea, Ohio, in the 1940s, a young Collins woke to the same hypnotic rhythm of popping sounds each morning.

“Puh...puh...puh...”

These pleasantly steady vibrations reached Collins from the four dirt tennis courts that stood 50 yards from his window. Collins’ favorite sport to play was baseball, but he loved to watch tennis—and to hear it.

As summer wound down, Collins and friends would gather on his fire escape to listen to another series of “puh...puh...puh” sounds, from farther away. Through a portable radio, they followed the action at the U.S. Nationals in New York, as described by announcer Lev Richards.

Collins could only dream of what the players looked like as he listened to Richards “sing his siren song of a green and glorious place where bronzed Australians, Californians and other exotics played like deities.” In Richards’ voice, Forest Hills had a mystery that television would never conjure: “Who could picture a game of tennis on grass?”

In 1947, Collins saw one of those deities, Jack Kramer, on the cover of Time. He could listen no longer. When Kramer, who was turning pro, played at Forest Hills for the final time that August, Collins vowed to be there. A 26-hour drive brought Collins and two friends to the West Side Tennis Club.

“Dazzled, we beheld a strange and gorgeous meadow,” Collins recalled. “No tennis court had ever looked like this one. Yes, it was grass.”

The Arthur and Arthur Show: Ashe, Collins and the 1968 US Open

Advertising

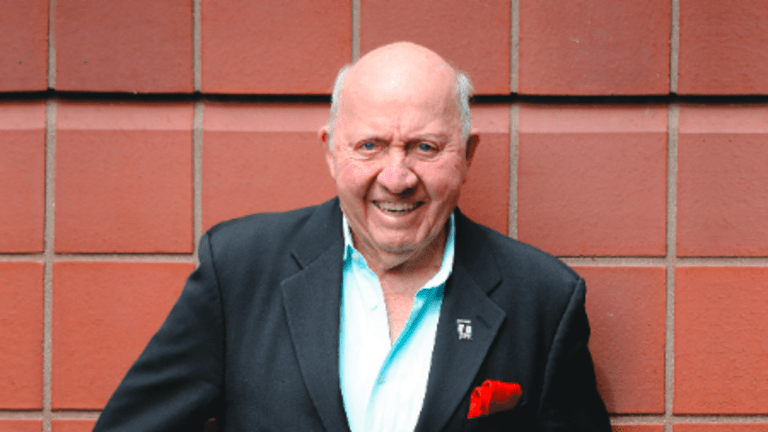

Unmistakable in person and in print, Collins (above), helped connect the game's signature moments, including Ashe's triumph at the 1968 US Open, to a burgeoning fan base.

A decade after Collins was roused by the sounds of tennis in Ohio, Ashe had a similar experience in Virginia. In his case, he wasn’t listening to a ball go “puh...puh...puh.” He was making the racket himself by pounding a ball against a backboard.

Like Collins, Ashe lived within listening distance of tennis courts.

His father, Arthur Sr., worked at Richmond’s Brookfield Park, a recreation area for African-Americans, and the family lived on its grounds. Brookfield was no match for whites-only Byrd Park, with its 16 well-maintained courts, but Ashe didn’t care. It became a refuge from his circumscribed world in segregated Richmond.

“The field behind my house was like a huge backyard,” he said. “I thought it was mine.”

While Collins spent his youth dreaming of Forest Hills, for the thin, often-sickly Ashe, those grass courts existed almost beyond the imagination, up north where blacks had begun to play on the same lawns as whites. In 1950, a month after Ashe’s seventh birthday, Althea Gibson became the first African-American to enter the U.S. Nationals.

At 10, Ashe started working with Gibson’s coach, Dr. Robert Walter Johnson. “Dr. J” had helped guide Gibson to Forest Hills; now he was searching for a player with the temperament to perform an equally difficult task: winning the traditionally all-white National Interscholastics in Charlottesville, VA. Eight years later, Ashe won the tournament without dropping a set.

At the moment of triumph, Ashe’s mind, like Collins’ mind years earlier, gravitated toward New York.

“I thought it was conceivable,” Ashe told author John McPhee, “that I might win someday at Forest Hills.”

The Arthur and Arthur Show: Ashe, Collins and the 1968 US Open

Advertising

Ashe wasn’t the only Arthur who was on the heels of Gibson. By 1956, Collins was working at the Boston Herald, where he was the lone reporter with any interest in tennis. One day his editor rattled off a surprising series of questions.

“How good is the colored girl?” he asked. “Could she win at Forest Hills? [She’d] be the first of her kind to win, if she does, wouldn’t she?”

The editor didn’t know Gibson’s name, but he knew that a black woman winning the U.S. Nationals was a story. When Collins offered to pay for the trip himself, the paper sent its first correspondent to Forest Hills.

But it wasn’t until 1963 that Collins and tennis came together for good. That year, a producer at fledgling WGBH called Collins with an outlandish proposal: he wanted to show the National Doubles, which was held at Longwood, in prime time, and he wanted Collins to do the commentary. An unlikely TV star was born.

That same year, Collins was hired by the Boston Globe. The paper’s liberal editors were committed to the Civil Rights Movement, and they were tennis buffs.

“Ashe is a good story,” Collins was told. “Hang on for all it’s worth.”

In 1965, Collins followed Ashe to his homecoming tournament in Richmond, where he played in previously whites-only Byrd Park. In 1967, he followed Lieutenant Ashe to Vietnam, where he gave tennis clinics. In 1973, he followed Ashe to Johannesburg, where he integrated the South African Open. Collins’ reporting helped raise Ashe’s profile, and the sport’s.

At Longwood, Ashe returned the favor by helping make Collins a national figure. After their post-match conversation, Collins received a call from Jack Dolph, an executive at CBS, which was broadcasting the US Open.

“Liked the job you did,” Dolph said, “especially the interview with Ashe. Would you be interested in doing the Open for us?”

Thirty years after he first heard that elegant phrase float out of a radio in Ohio, Bud would be the one saying it: “Live from Forest Hills...”

The Arthur and Arthur Show: Ashe, Collins and the 1968 US Open

Advertising

Ashe, who won three Grand Slam singles titles, would be forever associated with the US Open. The tournament's largest stadium bears his name; inside it is the Bud Collins Media Center.

While Collins was making his journey as a writer and commentator, Ashe was making one as a player and political activist. In both spheres, he grew more confident and assertive as the ’60s progressed.

Instinctively cautious, Ashe had never been a radical. The Nation of Islam and the militants at his school, UCLA, had reminded him of the segregationists he left behind in the South. Ashe would remain a follower of Martin Luther King’s integrationist approach; yet a letter Ashe received from King in 1968 pushed him to make more of his privileged status.

“Your eminence in the world of sports and athletics,” King wrote, “gives you an added measure of authority and responsibility.”

That year, Ashe gave a political speech at a black church in Washington, D.C., spoke about a boycott of the Summer Olympics and Davis Cup, and offered opinions on South Africa.

“Not a stone thrower,” is how Ashe described himself to Collins, “although I sense the hopelessness of those who throw stones, the rioters.”

The Arthur and Arthur Show: Ashe, Collins and the 1968 US Open

Advertising

Was it a coincidence that, as Ashe spoke out more, his game improved? In July 1968, he won 26 straight matches and took over the top U.S. ranking. At the U.S. Amateurs, Ashe beat Bob Lutz in a five-set final; in Forest Hills, he reached the fourth round without dropping a set. There he was expected to meet Rod Laver; instead, Cliff Drysdale upset the top-seeded Aussie.

In Drysdale, Ashe faced a new kind of challenge. Many believed he should boycott the match with the South African, but Ashe knew Drysdale was against apartheid. Ashe also believed he could do more for blacks by showing his skill on a tennis court.

“He proved his own superiority,” wrote Arthur Daley of the New York Times approvingly of Ashe. “If he would have withdrawn in protest...he would have proved nothing.”

Ashe went on to prove his superiority over the field. With his five-set win over Tom Okker in the final, he became the first black man to win a major. Collins called the final for CBS.

Afterward, Collins rushed to Ashe, hoping to continue their Longwood conversation for a larger audience. Instead, he heard a producer’s voice: “Don’t get into all that black stuff—just tennis.” CBS had ads to run.

“Friends who were watching told me I looked as though I’d been stabbed,” Collins said.

Tennis only had so much time for revolution. But the two Arthurs brought the sport to a new audience in 1968, and established roles they would play for decades: Collins would become the voice of the game, and Ashe would become its conscience.

The Arthur and Arthur Show: Ashe, Collins and the 1968 US Open

Advertising

Wake up every morning with Tennis Channel Live at the US Open starting at 8 a.m. ET. For three hours leading up to the start of play, Tennis Channel’s team will break down upcoming matches, review tournament storylines, breaking news and player developments.

Tennis Channel’s encore, all-night match coverage will begin every evening at 11 p.m. ET, with the exception of earlier starts on Saturday and Sunday of championship weekend.

Watch the best matches from the first three Grand Slams on Tennis Channel PLUS. From Federer’s historic win at the Australian Open to Halep’s breakthrough at Roland Garros. It all starts Monday, August 27th.

Follow the Race to ATP Finals this fall on Tennis Channel PLUS. Live coverage from the biggest stops including Beijing, Tokyo, Shanghai & Paris.