For our sixth annual Heroes Issue, we’ve selected passages from the last 50 years of Tennis Magazine and TENNIS.com—starting in 1969 and ending in 2018—to highlight 50 worthy heroes. Each passage acknowledges the person as they were then; each subsequent story catches up with the person, or highlights their impact, as they are now. It is best summed up with a quote from the great Arthur Ashe, that was featured on the cover of the November/December issue of this magazine in 2015: “True heroism is remarkably sober, very undramatic. It is not the urge to surpass all others at whatever cost, but the urge to serve others at whatever cost.”

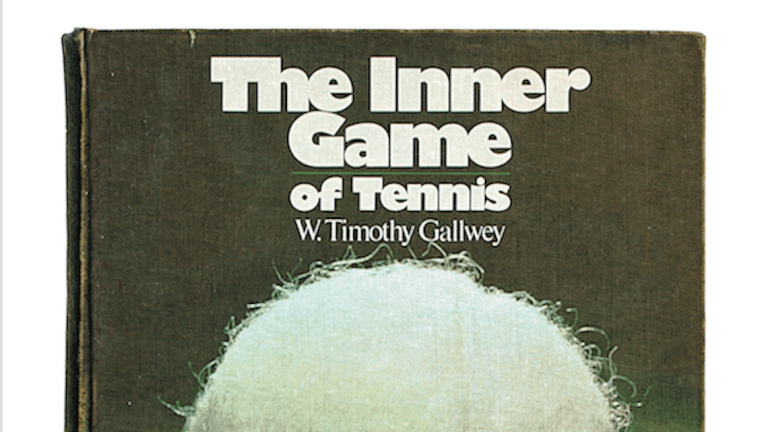

In this all-time best seller, Timothy Gallwey shows how to improve your game by overcoming bad mental habits. - "Book Service" / January 1978

It all started one day in the early 1970s, when Timothy Gallwey “was a little bored” while giving a tennis lesson.

“The guy had a backhand problem,” Gallwey remembers. “This time, instead of telling him what he was doing wrong, I let him swing away at it. Pretty soon I noticed that his backhand was getting better without any instruction at all.”

This strange sight made Gallwey wonder: was “teaching,” in the traditional sense, the best way to help someone learn a sport? Similar epiphanies soon followed, most of which led him to the conclusion that, when it comes to improving your game, the best thing you can do is get your brain out of your body’s way.

By 1974, Gallwey had gathered his zen-like revelations into The Inner Game of Tennis. The book would become a best-seller, and the Bible of the sport’s boom years.

That’s not all this most cerebral of how-to tomes turned out to be. Now 80, Gallwey, a former captain of the Harvard tennis team, has spent much of the last two decades coaching executives in boardrooms rather than hackers on tennis courts, and he presides over a publishing empire that includes Inner Skiing, The Inner Game of Golf, The Inner Game of Music and The Inner Game of Work. Tom Brady himself has sung the praises of The Inner Game of Tennis.

“I’m shocked at the number of uses people have made of I.G.,” Gallwey says.