US Open

Rocket's Revolt: Rod Laver's miraculous Slam-winning summer of 1969

By Steve Tignor Sep 08, 2019US Open

Coco Gauff led the way, but it was a wildly successful US Open for American tennis at large

By Peter Bodo Sep 13, 2023US Open

Daniil Medvedev was stubborn to a fault at the US Open, but still came away a winner

By Peter Bodo Sep 13, 2023US Open

With the Grand Slam season in the books, what's the state of the ATP Tour in 2023?

By Joel Drucker Sep 12, 2023US Open

Four Grand Slam winners, five storylines: The state of the WTA in 2023

By Joel Drucker Sep 11, 2023US Open

Novak Djokovic put on one of his most impressive physical and tactical performances to win a 24th Grand Slam title

By Steve Tignor Sep 11, 2023US Open

Novak Djokovic wins the US Open for his 24th Grand Slam title by beating Daniil Medvedev

By Associated Press Sep 11, 2023US Open

Novak Djokovic has won 24 Grand Slam titles. Here is a look at each one

By Associated Press Sep 11, 2023US Open

Djokovic celebrates No. 24 with a tribute to Kobe Bryant, who wore that number and became a friend

By Associated Press Sep 11, 2023US Open

Novak Djokovic's US Open title gives him 24 Grand Slam titles. No one in tennis history has won more

By Associated Press Sep 11, 2023US Open

Rocket's Revolt: Rod Laver's miraculous Slam-winning summer of 1969

The Australian's banner year has achieved mythic status, but its place in the sporting revolution of the ’60s remains under-appreciated.

Published Sep 08, 2019

Advertising

NEW YORK—Among tennis players, Rod Laver’s trophy collection is second to none. The replicas from the four Grand Slams and the Davis Cup are only the tip of the Australian great’s iceberg of awards. This is a man who, by the most comprehensive count available, won 200 tournament titles over the course of his 20-year career on the amateur and pro circuits.

Yet Laver’s most valued possessions also include a much more humble item: a coffee mug. It was given to him by his son, Rick, and on it are listed some of the most notable events from that most notable of years, 1969. Over the the course the fabled summer of ’69, the themes of a transformative decade reached their conclusions in a series of history-making events. Humans walked on the moon, a generation met and rolled in the mud together at Woodstock, the Kennedy myth dug a watery grave at Chappaquiddick, and a new and ultimately world-changing civil-rights movement was born at the Stonewall Inn in New York.

Along with a few of those well-known moments, Rick Laver included two other, more personal milestones from the late summer of ’69 on the mug. The first was his father’s calendar-year Grand Slam, which made him the only player to attain the sport’s Holy Grail twice. The second event was Rick’s arrival, just a few days after Rod completed his Slam at Forest Hills. “I WAS BORN” is the last line on the mug. “To me,” Laver said, “that piece of news should have headed the list.”

Those were obviously heady days in the U.S., and in the 31-year-old Laver’s life. In the 50 years since, as dozens of male Hall-of-Famers have tried and failed to match his achievement by winning all four majors in a season, Laver’s second Slam has been accorded mythic status, while the mild-mannered man ironically nicknamed Rocket has become the Joe DiMaggio of tennis, a universally venerated symbol of a purer and simpler time, when racquets were wood, clothes were white, and players played for love instead of money. It was hardly a surprise in 2017 when Roger Federer named his new team event the Laver Cup.

Despite this widespread recognition, the significance of Laver’s Slam, and how it fit into the sporting revolution that accompanied the political revolutions of that decade, is under-appreciated. The Rocket didn’t have long hair or a beard, and his politics were hardly radical, but his talent—which was equal parts flash and substance—made him the de facto leader, and freckled face, of tennis’ own ’60s rebellion. Looking at how far the sport has come in the last five decades, the professional revolution Laver helped lead might have been the most successful of any from that era.

Rocket's Revolt: Rod Laver's miraculous Slam-winning summer of 1969

© Anita T Aguilar

Advertising

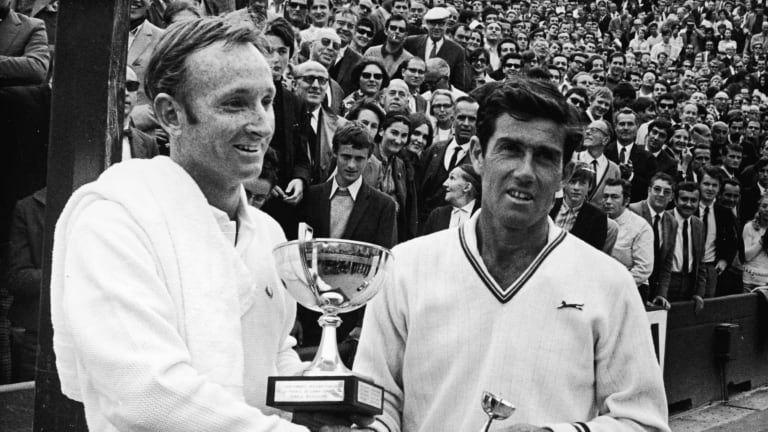

Laver completed his 1969 Grand Slam by defeating Tony Roche at the US Open. (Anita Aguilar/Tennis.com)

Not only was he trying to complete the Grand Slam, he was also riding a 23-match win streak, dating back to June at Queen’s Club.

“I had been fretting that my winning streak, one that was unprecedented in my career, would come to an end, as all purple patches do, at the US Open,” he wrote in his 2013 autobiography, Rod Laver.

That summer, he had been given one more reason to stress about the Slam.

With the advent of open tennis the previous year, professionals had finally been welcomed at the sport’s most important events, which began to offer prize money. As the pros walked through the gates at the Slams for the first time, they were accompanied by a new figure, the sports agent.

In 1969, Laver became the first tennis player to sign with IMG, sealing a partnership with Mark McCormack’s agency that would make multi-millionaires of players from Bjorn Borg to Serena Williams. One of McCormack’s first observations to Laver was that if he could manage to win the Grand Slam, he would make himself a more marketable commodity. But no pressure or anything.

Yet even Laver’s professional future wasn’t uppermost in his mind that August. That space was reserved for his wife, Mary, who was back at their Southern California home, eight months pregnant with Rick, their first child together.

“I was on the other side of the continent in New York,” Rod said, “while my heart was at home with her in California.”

But Mary’s approaching due date—it was the same day as the men’s final at the US Open—would turn out to be a blessing in disguise. Worrying about her left him less time to agonize about the Grand Slam.

Laver’s accommodations also served as a source of calm. The tennis-loving actor Charlton Heston, a friend, lent him his colossal triplex penthouse apartment in Tudor City, near the United Nations on Manhattan’s East Side. Laver hunkered down there with his friend and fellow player John McDonald of New Zealand, who served as his aide de camp through the fortnight. Together in their downtime they ate steaks, had friends over for drinks, listened to Aretha Franklin and Dave Brubeck on Heston’s hi-fi, and generally steered as clear as they could from the chaotic streets beneath their windows.

New York hadn’t escaped the turbulence of the late ’60s. Riots broke out in Harlem in 1967, and again after Martin Luther King’s assassination in April 1968. That year a teachers’ strike shut down schools in Brooklyn for months. In July 1969 the Stonewall uprising lasted for nearly a week on the streets of Greenwich Village. As Laver took up residence in Tudor City, many of the metropolitan area’s young people were staggering home from Woodstock, which took place two hours north.

Rocket's Revolt: Rod Laver's miraculous Slam-winning summer of 1969

© Getty Images

Advertising

Laver defeated Ken Rosewall in the 1969 French Open final. (Getty Images)

They began in January, when the New York Jets won Super Bowl III. With Joe Namath playing quarterback and brazenly guaranteeing victory, the Jets pulled off one of the biggest upsets in football history when they beat the heavily-favored Baltimore Colts.

But even that surprise victory paled next to the miracle that was unfolding in Queens during those late-summer weeks. As the US Open began nearby, the New York Mets, led by their own superstar, Cy Young-winning pitcher Tom Seaver, were in the midst of a flabbergasting 26-6 run that would catapult them into first place. Through their seven-year existence, the Mets had been one of the laughingstocks of American sports, never finishing higher than ninth in a 10-team league. By the end of October, they had won the World Series.

Whether he knew it or not, Laver had much in common with Namath, the Jets and the Mets.

The Jets’ Super Bowl win was also the first victory for the upstart AFL over the establishment NFL. The AFL had been founded in 1960 by Lamar Hunt, the Texas oilman who would go on to bankroll WCT, the men’s pro tennis circuit that Laver would soon join. And while he would never don a fur coat or earn a nickname like Broadway Joe, Laver’s talent and fame helped legitimize pro tennis in the same way that Namath’s legitimized the AFL.

The Mets made their debut in 1962, and promptly lost an all-time record 120 games. By the end of that season, the idea that they would win a World Series before the decade was out would have seemed laughable. Laver also turned pro in 1962, after winning his first calendar Grand Slam as an amateur that year. Exiled from Wimbledon and Forest Hills, he suddenly found himself in the pro-tour wilderness, barnstorming with three other players by station wagon from one town to the next, laying down a canvas court in any gym, skating rink or dance hall would would have them. Wimbledon was so incensed by his decision that officials there wrote a letter asking him never to wear the mauve-and-green club tie that they had presented him when he won his first title there. For five years, Laver would play in exile; at a certain point, the idea that he would someday return to win all four Grand Slams in a single year would have seemed fantastical.

Advertising

Maybe there was some voodoo in the New York air that summer. On Sept. 9, Laver played the US Open final in the afternoon. A few hours later, the Mets played their closest rivals, the Cubs, who still held a narrow lead over them in their division. In the fourth inning, a black cat appeared on the field at Shea Stadium, and slowly began to prowl along the length of the Cubs dugout. Some players said it stopped and stared at the Cubs’ manager, Leo Durocher, before disappearing from the field. The Mets won the game, and the Cubs never challenged them again in the pennant race.

Was a more powerful force watching over Laver in 1969 as well?

“I couldn't put a foot wrong that year,” he said.

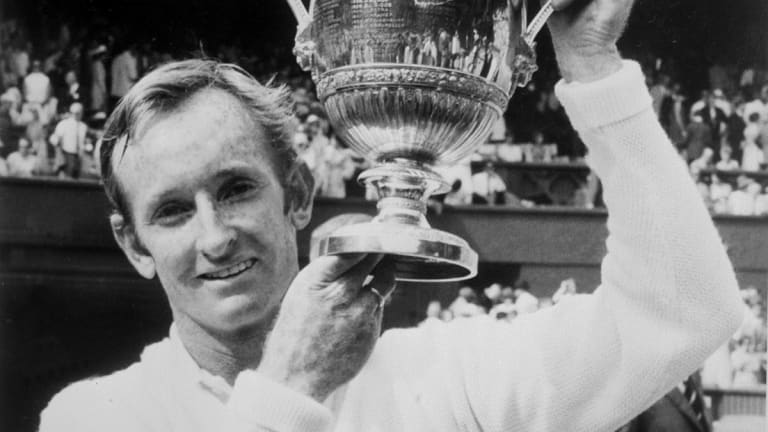

Each of Laver’s three major titles had come with a Houdini-like escape. At the Australian Open, he and his friend Tony Roche “were at each other’s throats” for 90 games and four and a half hours, in 100-degree heat, before Roche got what virtually everyone agreed was a horrendous line call while serving at 4-3 in the fifth set—Roche raged at the injustice, then fell apart. At Roland Garros, Laver fell behind another Aussie, Dick Crealy, by two sets to love in the second round; this time a rain delay, and a botched putaway by Crealy on a crucial point, saved him. At Wimbledon, it was little-known Indian Premjit Lall’s turn to give back a two-set lead and miss his own sitter volley at the wrong moment.

“The cement settled in his elbow a little bit,” Laver said.

That was enough to launch the Rocket, who won 15 games in a row to close out the match.

Through the first three rounds at Forest Hills, Laver had been, as he said, “at peace with myself.” He had beaten three Latin American players in straight sets, and taken satisfaction in the record crowds that flowed into Forest Hills that year and filled its famous horseshoe stadium each time he appeared.

Rocket's Revolt: Rod Laver's miraculous Slam-winning summer of 1969

© AFP/Getty Images

Advertising

Laver captured the 1969 Wimbledon crown with a four-set win over John Newcombe. (Getty Images)

Many had come specifically to see him go for the Grand Slam, while others had come to get a glimpse of the man whose legend had only grown during his years away. While Laver the person had disappeared from the amateur game after his 1962 Grand Slam, his name, and the memories of his swooping, carefree game, remained.

The following summer, in 1963, the amateur circuit wound its way back to the Longwood Cricket Club near Boston, where the U.S. National Doubles was held. The Rocket, who had played the event the previous year, was sorely missed, especially by a 13-year-old named Julie Hickey. She had become a fan of Laver’s while watching him dart across Longwood’s grass in ’62; according to Bud Collins, Hickey walked around the club in ’63 asking anyone who would listen, “Where’s Rod Laver?” When she was told that he couldn’t play because he was a pro now, Hickey said, “That’s dumb. Doesn’t everyone want to see him?”

Tennis’ amateur officials had no good answer for that. But Hickey’s father, Ed, did. He was the head of the public relations department at New England Merchants Bank in Boston, and his daughter’s question gave him an idea: Why not have the bank sponsor a pro tournament at Longwood? In 1964, the U.S. Pro began its long, successful run at the club, with a then-unthinkable $10,000 purse.

“To us,” Laver said, “10,000 dollars seemed like a million.” To the delight of Julie Hickey, Laver took the $2,200 winner’s check.

Professional tennis had made a leap, from one-night-stands in high school gyms to full-fledged tournaments in private clubs. The pro game, on the strength of Laver’s appeal, had successfully invaded the amateurs’ turf for the first time. While he and his fellow outlaws would be forced to wander in exile for four more years, they were finally welcomed at Forest Hills for the first US Open in 1968.

Advertising

Was Laver angry about losing five years of his prime? That’s probably too strong a word to describe the reserved Rocket. But the disdain he had always felt from the guardians of amateur tennis, particularly those in his home country, fueled him in ’69.

“We knew there were officials in the crowd who resented our presence,” Laver said when remembering his 90-game epic against Roche at the first Australian Open, in January ’69. “So we both went out determined to play our best tennis, to hold the flag high for ourselves and our fellow pros.”

Laver was going to make up for lost time.

The fans who streamed into the Open in ’69 may have waited for years to see the Rocket play, but they had no trouble rooting against him when he faced an American, Dennis Ralston, in the fourth round.

“Their cheers were almost ecstatic when [Ralston] walked to the baseline after we’d had a breather when we changed ends,” Laver said. “When I stepped up there’d be a deafening silence and baleful glares.”

“It was a living, breathing wake-up call that I was not going to win this tournament without a mighty struggle.”

As Ralston built a two-sets-to-one lead, the cheers for him only grew louder. Years earlier, Laver’s old coach, Harry Hopman, had taught him a sly solution to this away-game problem: After a changeover, time your return to the court to coincide with your opponent’s. When Ralston walked to his baseline, Laver walked to his. Voilà, the American’s cheers became his, too.

Hopman’s old trick boosted Laver emotionally. It was left to two other Aussies to help him technically. In those days, there was still a 10-minute break after the third set at the Grand Slams; as Laver headed to the locker room, he was joined by Roy Emerson and Fred Stolle, who had noticed something about their old mate’s serve: His toss was too low. A few more inches made all the difference over the last three sets.

“Their advice paid dividends,” Laver said of this little piece of in-match coaching, which wouldn’t be allowed at the Open today.

Laver leveled at two sets each. All that was left was for him to have fortune smile on him once again, and for Ralston to open the door in the fifth.

“I think this was in the back of both of our minds when we played,” Laver said. “When we got to the critical point, he was going to crack.”

That wouldn’t always be the case; Ralston would beat Laver at the Open in 1970. (“I’ve had to revise my estimate of him,” Laver admitted.) But this was 1969, not 1970, which meant that Laver would be correct, and Ralston would crack. Down break point at 2-3 in the fifth set, the American missed an easy backhand volley. “I think he was trying to make it a shade too good, as you will when you’re pressing,” Laver said.

Laver would press on, past Ralston, and toward a quarterfinal confrontation with Emerson. First, though, he had to wait out unwelcome intermission—over the next 48 hours, more than six inches of rain fell in Queens. The Open’s flimsy tarps didn’t help protect the grass much, either. During his quarterfinal with Laver, Emerson’s habit of dragging his back foot on his serve began to tear up chunks of the sodden turf. After a while, “his back foot began to get caught in the sludge,” said Laver, who didn’t have the same problem because he didn’t drag his foot on his serve.

“In the end, it was the court as much as me that ended [Emerson’s] US Open,” Laver said. Even a two-day rainstorm had worked to his advantage. It would work to his advantage one more time, in the final.

Rocket's Revolt: Rod Laver's miraculous Slam-winning summer of 1969

© Anita T Aguilar

Advertising

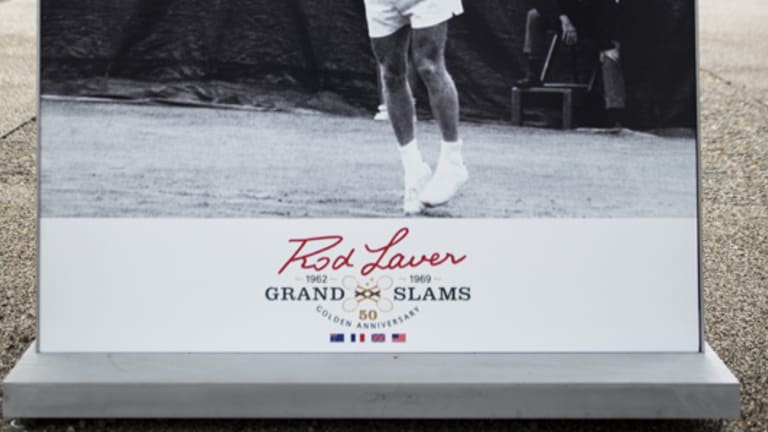

(Photo of kiosk by Anita Aguilar/Tennis.com)

Tony Roche would finish 1969 with a 5-3 record against Laver, but what he wanted on this day was revenge for the bad call that he still believed—and believes to this day—robbed him of their Australian Open semifinal. But both men would have to wait for their rematch. Steady rain delayed the final for two more days. Open officials lowered a helicopter to within a few feet of the playing surface, in the hope that its whirling blades would speed up the drying process. But they only brought the water closer to the surface. Laver and Roche, two farm boys from the Australian bush country, spent the day side by side chatting with the press in the old Forest Hills clubhouse—something else that would be hard to imagine today. Laver ducked away when he could to call Mary, who had reached her due date the previous day.

“It’ll be just my luck to go into labor when your match is on TV,” she told him.

Finally, on Tuesday the 9th, two days after the tournament was scheduled to end, Laver walked out to try to complete his sweep of the four tournaments that had banned him for half a decade. The grass was soggy, the seats in the horseshoe stadium were half full, and the muscular Roche looked formidable. But Laver had one more trick up his sleeve.

“I was confident that I’d handle the sludgy surfaces better than Tony,” he said, “because I had played on much worse surfaces time and again as a pro….Rochey was only a recent arrival in the pro ranks and had spent most of his career playing on pristine, perfectly maintained courts.”

When Laver began slipping and sliding around in the mud, he asked tournament referee Bill Talbert if he could put on spikes. Talbert, knowing this was the last match of the tournament, gave the OK. Laver donned the spikes, while Roche stuck with his normal sneakers because of a recent thigh strain. Laver had made the right move again. Through his four-set win, the spikes kept him upright, while Roche continued to hit the deck. That’s how the match and the Grand Slam ended, with Roche flat on his back, as his final forehand sailed long.

Laver had won in high Australian heat, on red clay and slick grass, and in the rain-soaked earth in New York. At Forest Hills, USLTA president Alastair Martin presented Laver with a then-astronomical $16,000 winner’s check, and spoke for tennis fans everywhere when he said, “You’re the greatest in the world, perhaps the greatest we’ve ever seen.”

Through it all, Laver kept up his reserve, but now that the job was done and history was made, he briefly threw his customary caution to the wind. Only once before, in 1957, had he tried to jump the net after a victory; when he caught his foot on the tape and fell flat on his face, he vowed never to try it again. Now, before he even knew what he was doing, he found himself in midair.

“In my euphoria, I broke one of my rules and leapt over the net,” Laver said. “Even before my feet hit the ground, I felt a fool.”

Embarrassed or not, the Rocket flew across the net—safely this time—and into history. No man has followed him there yet.

Rocket's Revolt: Rod Laver's miraculous Slam-winning summer of 1969

© Anita T Aguilar

Advertising

(Photo of kiosk by Anita Aguilar/Tennis.com)

Fifty years later, though, the mythic pull of Laver’s second Slam is still in evidence. This year, kiosks featuring vintage photos from each of his four major-title runs in ’69 have lined the grounds at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center.

The Flushing Meadows facility, which opened in 1978, is not the house that the Rocket built. That honor goes to King, Jimmy Connors, Chris Evert and other legends from the U.S. tennis boom of the 1970s. But Laver’s Slam helped kick off that boom, and helped tennis takes its place alongside other big-money sports for the first time. It’s not an accident that he achieved it in the same year that Namath was raising the profile of professional football, and baseball player Curt Flood was challenging that sport’s reserve clause, which allowed team owners to essentially control their players for life. The result of Flood’s lawsuit, which went to the Supreme Court, was the advent of free agency, which has tipped the scales of power in the players’ direction ever since.

The open tennis revolution did much the same thing for its own players. Before 1968, they has been under the control of their national amateur federations, which had the power to decide who could enter events like Wimbledon and Forest Hills. By the early ’70s, the players were running the tours and making their own decisions about where to compete. While other democratic revolutions of the ’60s stalled, the sports revolution of that era succeeded in permanently overturning old class hierarchies.

All of that was in the future on September 9, 1969, and it’s safe to say none of it was on Laver’s mind. He had one more thing to do after his victory: call Mary. The problem was, he didn’t have a dime for the pay phone at Forest Hills. Finally, he found a charitable reporter who loaned him one. “I’m good for it,” Laver joked, holding up his $16,000 check. He told his wife he would be on the first flight home the next morning.

Nineteen days later, Rick was born, and Laver’s year of miracles was complete. He still has the mug to prove it.

Rocket's Revolt: Rod Laver's miraculous Slam-winning summer of 1969

Advertising

Wake up every morning with Tennis Channel Live at the US Open, starting at 8 a.m. ET. For three hours leading up to the start of play, Tennis Channel's team will break down upcoming matches, review tournament storylines and focus on everything Flushing Meadows.

Tennis Channel's encore, all-night match coverage will begin every evening at 11 p.m. ET, with the exception of earlier starts on Saturday and Sunday of championship weekend.