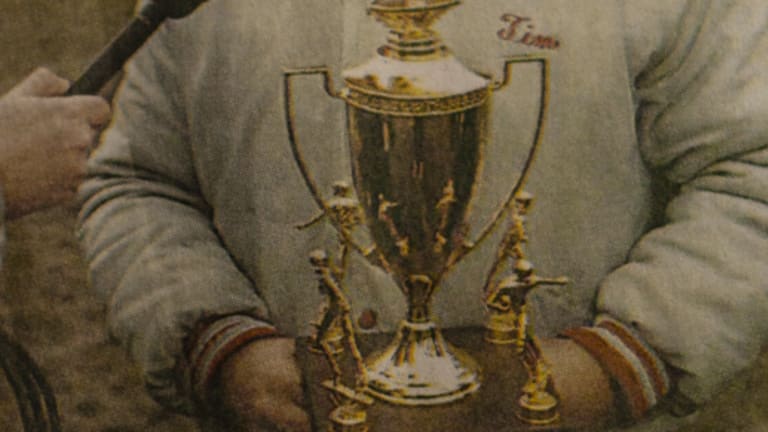

Williamsport's Tim Montgomery lived football—but he loved all athletes

By Sep 18, 2019Brian Tobin, former president of the International Tennis Federation, dies at age 93

By Apr 24, 2024Madrid, Spain

Elena Rybakina is a sore winner (this is a good thing)

By Apr 23, 2024Zendaya, Josh O'Connor and Mike Faist on the steamy love triangle of 'Challengers'

By Apr 23, 2024Madrid, Spain

Tatjana Maria will follow daughter Charlotte’s first tournament on live scores from Madrid

By Apr 23, 2024Madrid, Spain

“I hope to make it”: Carlos Alcaraz eyes Madrid three-peat for 21st birthday gift

By Apr 23, 2024Betting Central

Line Calls, presented by FanDuel Sportsbook: WTA Mutua Madrid Open Betting Preview

By Apr 23, 2024Lifestyle

Without a driver's license, what will Elena Rybakina do with the Stuttgart Porsche?

By Apr 23, 2024Pop Culture

How does Taylor feel about Taylor? Fritz speaks on his appreciation for Swift

By Apr 23, 2024Pop Culture

Novak Djokovic named Laureus World Sportsman of the Year for a fifth time

By Apr 22, 2024Williamsport's Tim Montgomery lived football—but he loved all athletes

Remembering a legendary high school football coach, and what he had to teach a tennis player.

Published Sep 18, 2019

Advertising

Williamsport's Tim Montgomery lived football—but he loved all athletes

© 2017 Getty Images

Advertising

Williamsport's Tim Montgomery lived football—but he loved all athletes

Advertising

Williamsport's Tim Montgomery lived football—but he loved all athletes

© 2017 Getty Images