Centre Court turns 100 this year. During that time, this bastion of propriety and tradition has also borne witness to a century’s worth of progress and tennis democratization. For its centennial, we look back at 10 of its most historic and sport-changing matches.

#CentreCourtCentennial

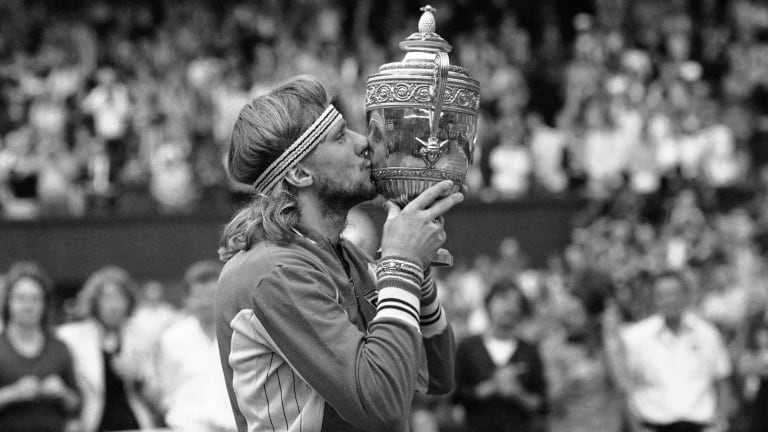

1980: The five-set final between Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe was the pinnacle of their rivalry—and the Woodstock of their tennis era

By Jun 20, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

Serena Williams' energetic return to Centre Court after a year away from the game was a brave effort, and one worthy of her legend

By Jun 29, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

2009: The first full match under Centre Court's roof showcased British tennis' newest Wimbledon title contender, Andy Murray

By Jun 23, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

2008: Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer produced a quantum leap in quality and entertainment in their classic, daylong final

By Jun 22, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

2007: After fighting for pay equity at Wimbledon, Venus Williams became the first woman to collect an equal-sized champion’s check

By Jun 21, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1975: In defeating a seemingly invincible Jimmy Connors, Arthur Ashe showed that with enough thought and courage, anyone in tennis can be beaten

By Jun 19, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1968: At the first open Wimbledon, Billie Jean King receives her first winner’s check—and notices a “big difference” with her male counterparts

By Jun 18, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1967: With the Wimbledon Pro event, professional tennis finally comes to the amateur game’s most hallowed lawn

By Jun 17, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1957: “At last! At last!” Althea Gibson fulfilled her destiny at Wimbledon, and with every win she opened up the sport a little wider

By Jun 16, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1937: With a World War looming and one man playing for his life, Don Budge and Baron Gottfried von Cramm stage a Davis Cup decider for the ages

By Jun 15, 20221980: The five-set final between Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe was the pinnacle of their rivalry—and the Woodstock of their tennis era

In its setting and place in time, this Wimbledon final serves as a poignant reminder of a golden era now long past, when tennis reached a peak of popularity and cultural influence it would never reach again.

Published Jun 20, 2022

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

Advertising

Advertising

This marked Borg's fifth and final crown at SW19. A year later, McEnroe would celebrate his first Wimbledon singles triumph in defeating the Swede over four sets.

© ASSOCIATED PRESS