ATP Finals

A future ATP Finals staged on clay—why not?

By Nov 22, 2022ATP Finals

Inspired by Nadal, Cahill, respect abounds in Alcaraz-Sinner rivalry

By Nov 20, 2025ATP Finals

How the rivalry between Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz dominated tennis in 2025

By Nov 17, 2025ATP Finals

ATP Finals takeaway: Jannik Sinner walks the walk on making changes to Carlos Alcaraz matchup

By Nov 16, 2025ATP Finals

Jannik Sinner tops Carlos Alcaraz to retain ATP Finals title, ends 2025 on 15-match win streak

By Nov 16, 2025ATP Finals

Carlos Alcaraz meets Jannik Sinner for ATP Finals trophy | Preview, Pick, Where to Watch

By Nov 15, 2025ATP Finals

"Felt like I could do everything": Carlos Alcaraz books dream ATP Finals title tilt with Jannik Sinner

By Nov 15, 2025ATP Finals

ATP Finals: Carlos Alcaraz vs. Felix Auger-Aliassime | Preview, Pick, Where to Watch

By Nov 14, 2025ATP Finals

Felix Auger-Aliassime: "Beautiful night" in Turin came from riding wave of self-belief against Alexander Zverev

By Nov 14, 2025ATP Finals

ATP Finals: Alex de Minaur vs. Jannik Sinner | Preview, Pick, Where to Watch

By Nov 14, 2025A future ATP Finals staged on clay—why not?

Now that the emphasis on hard courts has produced more well-rounded performers, it might be nice to watch them battle it out for the ATP's crown jewel on rotating surfaces.

Published Nov 22, 2022

Advertising

Advertising

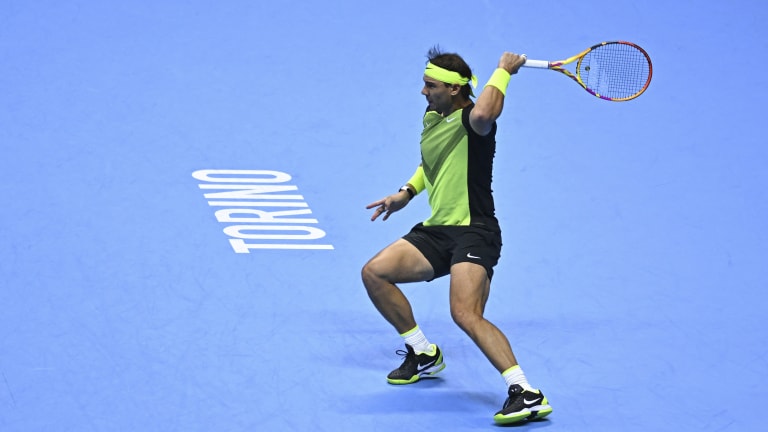

Nadal dropped to 21-18 lifetime at the ATP's season finale.

© Sipa USA via AP

Advertising

Many players wear wristbands when they compete, with backups to swap out if needed.

© AFP via Getty Images