But what’s missing in luxury can be compensated by charm. In the six years it has hosted this event, The Landings has developed a growing list of sponsors, some of whom are promoted between games by a DJ who interrupts his Top 40 changeover playlist to make such announcements as: “This Wednesday, it’s Ladies’ Day with $8 admission for day and night sessions. Sponsored by the Savannah Tennis League, serving up great tennis since 1979.”

The lack of a barrier between community and player can also make for some feel-good moments. Tournament director Scott Mitchell recalls that, in 2013, Ryan Harrison and his coach went to a nearby store, loaded up their car with canned goods and brought them back for a local charity. On the less charming side, players’ adherence to certain Tour-level amenities can seem out-of-touch, as when they call “towel” to linespeople old enough to be their grandparents.

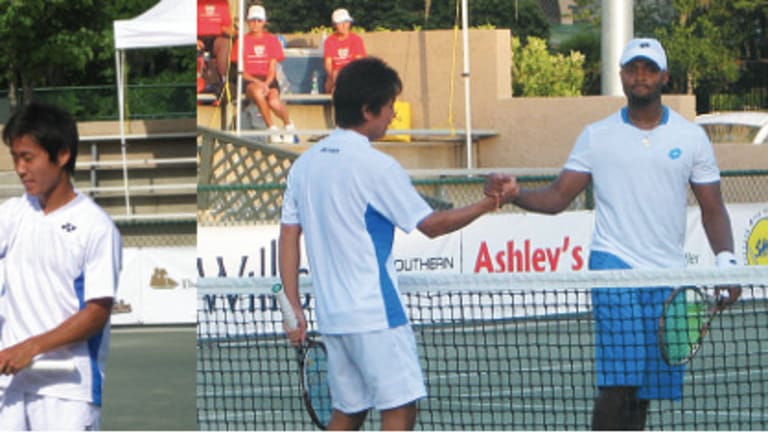

The dynamics of the matches themselves can be contradictory, as well. On the one hand, a refreshing camaraderie is displayed as players look to each other for line-call verification and offer one another heartier congratulations than what is usually witnessed on the bigger stages. On the other, the pressures of what’s at stake can be daunting.

“What people don’t understand is that if you win a Challenger you get 80 to 100 [ranking] points,” says Bobby Reynolds. “That’s like making the third round in a major. We’re out here beating each other up for the points. It’s not for the money.”

Reynolds, an affable 31-year-old American, has played in a major as recently as the prior summer, when he qualified for Wimbledon, but he finds a lot to love on the Challenger circuit as well.

“To be at Grand Slams obviously is a different feeling of adrenaline,” he says. “But I can’t tell you how many people I’ve met across the country at these Challenger events who house me. It’s like an extended family whereas when you’re at a Tour event, it’s court-hotel court-hotel. Here it’s more casual.”

Reynolds also enjoys downtime with his fellow players on the fringe, where similar circumstances and a smaller crowd of players and fans make for war-buddy intimacy. He plays golf with Tim Smyczek and fishes with Alex Kuznetsov. “I don’t want to say it’s a fraternity,” Reynolds says, “but it is like that a little.”

Reynolds stays with local families on the road to save money, a common consideration among Challenger players.

“You win a Challenger at this level, it’s $7,000 or $8,000,” he says. “With the costs, you can’t piece it together. Let’s say you have a great year, you win three or four Challengers. That’s 30 grand. That’s not paying a coach. That’s not paying a mortgage back where you live.”

When he entered Savannah, Reynolds was thinking of hanging up his racquet after his last handshake in Georgia: “I have a kid at home,” he says. “It’s tough being away. I don’t want to be that father who’s gone 35 weeks a year to live a dream. I’ve been able to do it for 12 years. I went to Vanderbilt for three years, and am looking to go back and finish my degree. I will be able to find a pretty good job with that education.”

But buoyed by a first-round win in Savannah, Reynolds has already reevaluated, with his sights set on the qualifying tournaments for the majors that will take place later in the year.

At 23, Erik Crepaldi can afford to be more footloose than Reynolds. The Italian, whose home base is near Milan, is ranked in the 400s and in the last year has competed all over Italy, as well as in Switzerland, Turkey and Mexico, among other countries. He acknowledges that it’s difficult to soldier the solitude of traveling alone, but without any support from the Italian Tennis Federation, he can’t afford to have his father–coach along outside of his home country.

“But there’s a moment in tennis when you need to improve and need to learn many things, so it’s OK,” he says.

Crepaldi has just lost in the final round of qualifying, meaning that he earns neither ranking points nor prize money, but he had been steadily climbing the rankings to a career high of 416 last year, followed by a dip. At the moment, his roller coaster is climbing back up the rankings incline: A decent run at his last four tournaments has returned him almost to his personal best. This tournament began the day after Easter and Crepaldi sees a parallel: “Before you have the holy week, you need to suffer, then you can enjoy the life,” he says.