Gordon Forbes may have been the best former-athlete writer of all

By Steve Tignor Dec 11, 2020Novak Djokovic lands in Carlos Alcaraz half of BNP Paribas Open men’s draw

By David Kane Mar 03, 2026Aryna Sabalenka draws Naomi Osaka, Amanda Anisimova at BNP Paribas Open

By David Kane Mar 02, 2026Meet the newest addition to Aryna Sabalenka's entourage: her puppy, Ash

By TENNIS.com Mar 02, 2026How the Rwanda Challenger can be a blueprint for the growth of tennis in Africa

By Florian Heer Mar 02, 2026Aryna Sabalenka kicks off milestone 80th career week at No. 1 on the WTA rankings

By John Berkok Mar 02, 2026Is Carlos Alcaraz pulling away from Jannik Sinner?

By Peter Bodo Mar 02, 2026Iva Jovic and Learner Tien, once autograph-seekers at Indian Wells, return as ones to watch

By Steve Tignor Mar 01, 2026For Longhorns everywhere: Peyton Stearns, former University of Texas star, wins Austin title

By TENNIS.com Mar 01, 2026Aryna Sabalenka lives her best life at Gucci show during Milan Fashion Week

By TENNIS.com Mar 01, 2026Gordon Forbes may have been the best former-athlete writer of all

On the enduring magic of his amateur-era memoir, "A Handful of Summers."

Published Dec 11, 2020

Advertising

“I loved what you wrote about Roy Emerson,” my doubles partner said as we walked on court a few years ago. That month I had written a short tribute to Emmo for a best-players-of-all-time article for Tennis Magazine.

“‘Determined, rueful, kind, humorous,’” my partner continued, thinking he was repeated my words about Emerson back to me. “You really brought him to life.”

I nodded, said “Thanks,” and tried to leave it at that. But as we were warming up, I knew I couldn’t take credit where credit wasn’t due. Apparently my friend had forgotten that I had ended my tribute to the Aussie great with a quote from someone who knew him much better than I did.

“Actually,” I told him between forehands, “the part you like about Emmo was a description by another writer, Gordon Forbes.”

“OK,” my partner said, laughing. “Should I be reading him instead of you?”

The truth is, I didn’t mind making this confession. I’m always happy to be reminded of how memorable Forbes’ writing is, and happy to recommend it to a fellow tennis player. It wasn’t the last time a reader would see a quote from Forbes in one of my pieces and mention it to me later. It was always a pleasure to say, “Yeah, wasn’t that great?” about one of his gently poetic turns of phrase. I haven’t read every former athlete’s autobiography, but I have a hard time believing that any of them can hold a candle, sentence for sentence, to A Handful of Summers, and its sequel, Too Soon to Panic, the two humorously elegiac memoirs that the South African wrote—without professional help—about his adventures on the amateur tennis circuit of the 1950s and 60s.

Best Tweet of the day—I loved seeing everyone’s suggestions! Since we’ll all be inside for awhile, check out one of my favorite books, “A Handful of Summers” by Gordon Forbes. pic.twitter.com/76EunPDvqH

— Tracy Austin (@thetracyaustin) March 17, 2020

Advertising

That circuit has had a tough week. On Sunday, we received news of Dennis Ralston’s death, at 78, and yesterday we heard that Alex Olmedo had also passed away, at 84. The American and the Peruvian were fellow USC Trojans who became mainstays of the amateur era. In between, on Wednesday, we learned that Forbes, a different type of mainstay of that era, had died at 86. A quintessential journeyman as a player, he was a Hall of Famer as a storyteller. The game, its history, and how we think of it wouldn’t be as magical or romantic without him.

Forbes was mourned in tennis circles, but this being the niche sport that it is, his two memoirs aren’t as celebrated as they should be among the general sports-reading public. I only discovered him by accident myself, after I had already worked at Tennis Magazine for half a dozen years. I remember the moment well. Pete Bodo and I were standing outside the magazine’s offices on Madison Avenue in Manhattan, mulling over one of our favorite topics. Namely: Why aren’t publishers more interested in tennis books? As he was walking away, Pete said something like, “You can always try something like A Handful of Summers.”

“A handful of summers”? What did that mean? I liked the phrase, and couldn’t get it out of my head. Later, I scoured the magazine’s library and came across a well-worn mass-market edition of Forbes’ book that, for some reason, had an action photo of Rosie Casals on the cover (as far as I know, she doesn’t appear in its pages). I started reading and basically never stopped.

For years, when I traveled to cover tournaments, that ever-more-well-worn copy of A Handful of Summers traveled with me, and sat right behind my computer on my desk in the press room. Anytime I was stuck for a way to express an idea, I could open it to virtually any page and find something that reminded me of what lyrical writing sounds like. Forbes’ writing had, and still has, a way to dislodging words in my brain and making them flow more freely. It doesn’t take long to find an example; one of my go-to Handful of Summers paragraphs appears at the top of the second page. It’s a description of the start of the 1976 Wimbledon final between Bjorn Borg and Ilie Nastase; Forbes is making his first visit to Centre Court since the sport began to boom in the ’70s.

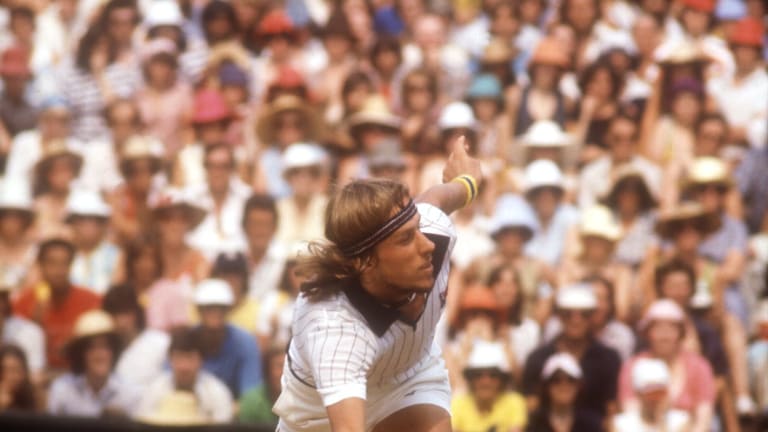

“At two, there came a crash of applause and Nastase and Borg appeared, superbly fitted out. Beautifully cut tennis gear. They took their bow, arranged their paraphernalia, and began to play; easy, expert strokes. Exclusive and aloof. There is no doubt at all that Borg is one of the game’s great athletes. There is a simplicity about the way he plays—a marvelous logic that carves away all complications.”

The short sentences and verbless phrases. The rapid movement from one image to the next. The general lack of cluttering adverbs. The marvelous logic that carves away all complications—Forbes could have been writing about himself when he described Borg’s game.

Gordon Forbes may have been the best former-athlete writer of all

© Getty Images

Advertising

Borg, playing Nastase in the 1976 Wimbledon final. (Getty Images)

Here’s another favorite, on his first trips through the British amateur circuit of the 1950s:

“They were so simple, those little English tournaments, so utterly artless. Homemade, if you like. Red clay courts, damp and heavy, clubhouses of old brick, and inside all the woodwork nearly worn out. Floors, tables, bashed-up little bars. They were funny things, those tournaments, but they were open-hearted, and they allowed ordinary people to play them.”

How’s this for a first, honest, look at Paris?

“How agonizing and unattainable is the appeal of Paris. There it lay, unforgettable in the mid-May sunlight, with its avenues and boulevards, fresh new leaves and sly sophisticates, all fashionably got up. That first evening we walked the Champs-Elysées—wide and sparkling, and the city touched us, although it was all then too rich—an acquired taste, like old whiskey, for people accustomed to lemonade.”

Here Forbes, by a stroke of luck, is on hand to see one of his favorite groups, the Modern Jazz Quartet, make its debut in Florence in 1959 and blow away a skeptical, black-tie, classical-music audience:

“John Lewis’ first chord comes out of the white piano like a solid living thing, all angles, like a sculpture. It’s ‘Django’—absolutely simple—each sound separate in these acoustics. Cascades of notes from Milt Jackson’s vibes; Percy Heath’s bass, plunging and lifting against the metal cymbals. Webs of sound, spun together, lifting off the stage like mobiles, balanced on silence. The audience are caught and held, somewhere between surprise and disbelief.”

Advertising

Here Forbes neatly sums up tennis’ two prevailing moods, and identifies their one common element:

Mood for winning: Loneliness plus courage, patience, optimism, concentration, a calm stomach, and a deep, quiet fury.

Mood for losing: Loneliness plus fear, a hollow stomach, impatience, pessimism, petulance, and a bitter fury at yourself.

As you can see, I could go on quoting Forbes all day. But you don’t have to be a writer in need of inspiration to cherish A Handful of Summers. Tennis fans will find a loving remembrance of youth, when Forbes was in his 20s and the game had a prelapsarian innocence to it. This was the post-war period, when air travel had made an international tour possible, but money had yet to flood the sport. There was more to tennis than just the bottom line then—there was fun, camaraderie and personality. Various types of people and playing styles could thrive in the amateur game, and Forbes gives them all their due, the gods and the oddballs alike.

On Lew Hoad: “Blond-headed, contemptuous of caution, nervousness, or any mannerisms remotely connected with gamesmanship, meanness, or tricky endeavor.”

On a young Ted Tinling: “A tall man in tennis clothes, who at first glance appeared to be all legs and piercing eyes, approached me and said, ‘Those shorts you’re wearing are appalling.’ Teddy looked me up and down. ‘Simply appalling. You have no knees. Come along with me. We shall have to rig you out.’”

Forbes even transforms Rod Laver, the most reticent of the Aussie legends, into a comical character: “Rodney would understate almost everything, especially his remarkable successes and superb tennis ability; like the unbelievable shots he sometimes pulled out of a hat when they were least expected and badly needed. These he would scrutinize soberly, before remarking: ‘Not a bad bit of an old nudge, would you say?’”

!

Laver, at Wimbledon in 1968. (Getty Images)

And then there’s Abe Segal, Forbes’ friend, countryman, doubles partner, extroverted opposite, and an all-around larger than life figure. There are too many great lines to quote about him here, so you’ll have to read the book to find out about the uproarious Abie.

How about the women? Near the end Forbes admits that, “I find that I have used up all my adjectives on the men players; I suppose because they are much easier for me to understand.” He does praise Billie Jean King for making the world, and presumably Forbes himself, take the women’s game seriously. But Handful of Summers ends in 1968, when the new era that King helped make—the Open era, the professional era, the WTA and ATP era—was just getting off the ground.

That year Forbes attended a reunion of amateur-era players at Wimbledon. During the fortnight, he came across his old friend and fellow jazz lover Torben Ulrich (father of Mettalica’s Lars), the oddest of the amateur oddballs, meditating cross-legged in the middle of an empty court. Ulrich had reserved the court for a practice session, and then spent half an hour “emptying my mind,” without hitting a ball. A few pages later, Forbes gives the philosophical Ulrich the book’s last word.

“‘After all, Gordon, what really is tennis,” Ulrich asks. And when I don’t reply, he says, ‘Only a game, you see. That is all that it really is. Only a game.’”

The implication we’re left with, of course, is that tennis is indeed only a game, but it’s also so much more. I don’t know of any better evidence of those two seemingly contradictory facts than A Handful of Summers itself.

RIP Gordon Forbes. If I’m lucky enough to have people mistake your writing for mine in the future, I promise to always give credit where credit is due.