“Life is good,” Jose Higueras says, sounding hale and hearty, from his home in Palm Springs.

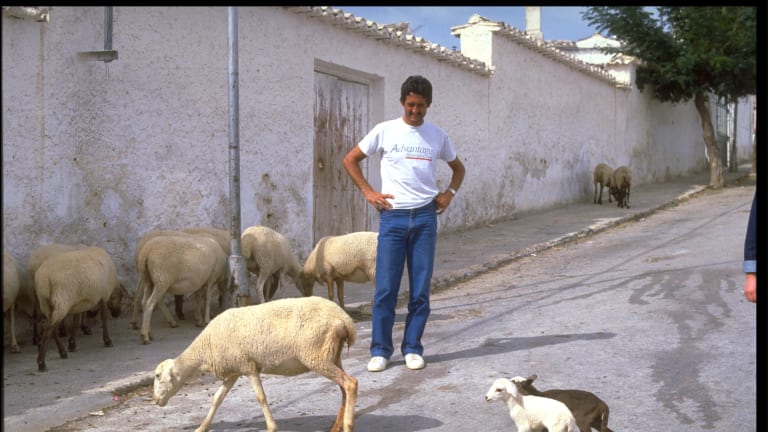

Granted, the desert in those parts is getting hotter by the day. The temperature reached 100 for the first time earlier this month, and it’s only going higher from there. Which means Higueras, 70 and mostly retired, is heading north to his place in Idaho for the summer. A highly respected tennis lifer who played for his native Spain for 16 years and coached in his adopted United States for even longer, Higueras now spends his time roping horses, enjoying the great outdoors, and spending time with his “brand new” granddaughter.

“I’m a frustrated cowboy,” he says with a laugh.

Still, he sounds no less passionate about tennis than ever. Like most fans, Higueras tunes in to see his young countryman Carlos Alcaraz tear up the competition as often as he can. Higueras was born in Diezma, Spain, a three-hour drive west from Alcaraz’s home region of Murcia.

“I think he’s a monster,” Higueras says of Alcaraz, in the kindest way possible. “He elevates tennis with the way he plays, and how positive and enthusiastic he is. Tennis is going to benefit from him.”