Before autumn's arrival on Saturday, we'll relive one of tennis' most memorable summers. The 1977 season was one of the most colorful and enduringly significant in the game's history. Over three days this week, we’ll celebrate the 40th anniversary of that most memorable of sporting summers.

Part 1: The Eternal Second—Guillermo Vilas' herculean, 145-win campaign still wasn't enough to make him No. 1

“It’s the day of the superstar,” Gordon Forbes thought as he took his seat inside a sun-drenched Centre Court to watch the 1977 Wimbledon men’s final. A 43-year-old ex-player from South Africa, he had known the All England Club in a simpler time, before the sport boomed and the masses invaded its lawns.

Forbes had returned, like dozens of his friends from the amateur days, for Wimbledon’s Centenary celebration. He wasn’t the only one among them to discover that, as he wrote, “Tennis has changed. Come into money and gone absolutely public.”

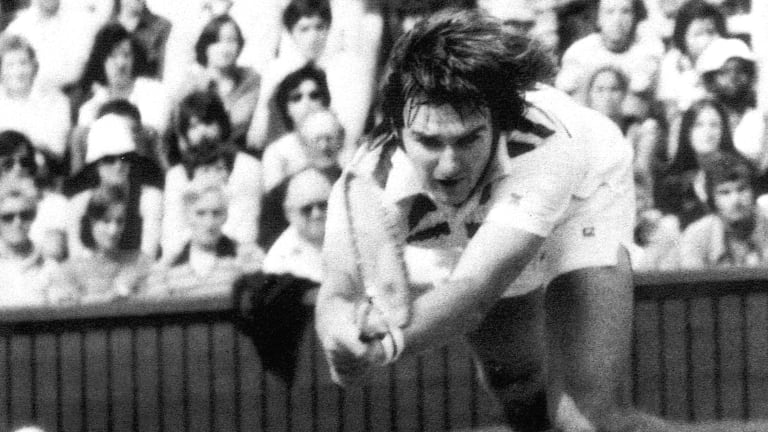

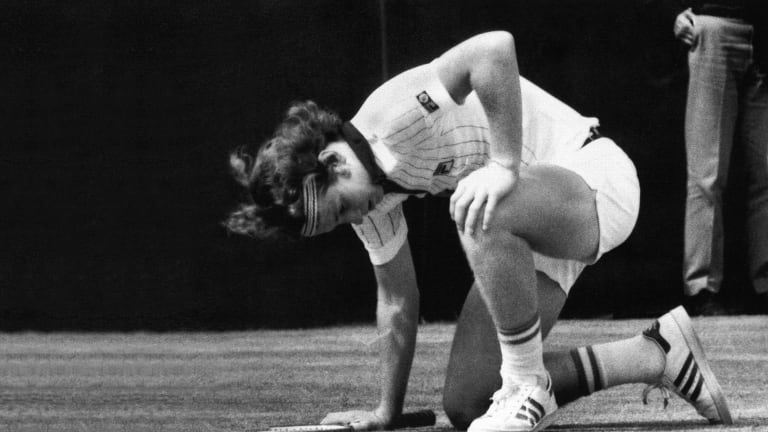

Looking down at the familiar well-worn grass, Forbes watched two of the superstars of the new game in action. Bjorn Borg, 21, and Jimmy Connors, 24, the first pure products of the Open era, were about to play a fifth set for the title.

“Marvelously detached. Inscrutable. Patient. There is a balance in his perspective,” Forbes marveled at Borg, as the Swede raced to a 4–0 lead.

When Connors roared back to make it 4–4, Forbes compared the American to “a complicated machine that has been finely programmed to hit hundreds of risky winners.”

Connors slapped his thigh and rolled his head like a prize fighter. Borg silently bent down into his return stance, showing no signs of the emotions roiling him. The championship was in the balance and Centre Court was on a knife edge.

It was the only way for this extraordinary fortnight to end. WIMBLEDON WAS NEVER BETTER, Sports Illustrated declared when it ended, and it was hard to argue. After 100 years, the ’77 edition showcased a men’s field that—in the form of semifinalists Borg, Connors, John McEnroe and Vitas Gerulaitis—had reached a peak of popularity, personality, quality and controversy.

Superstars had come to tennis, and the pro game was about to take a turn in the sun.