Vic Braden wasn’t drawn to tennis by watching the pros play. He wasn’t inspired by the elegance he saw in its strokes. And he didn’t play because his parents had played before him; Braden’s father was a coal miner who didn’t belong to the country club in Monroe, Mich., the blue-collar town that the family called home.

Braden was first hooked by the smell of tennis.

One day when he was 11, he walked past the local public courts, on his way to play football. At that moment, someone was opening a can of balls.

“You could hear the fizz,” Braden recalled in a 1989 interview with Time. “I could smell the rubber. It was an amazing kind of olfactory thing. I made up my mind I wanted one of those things.”

The next day Braden returned to the courts. Or at least he lurked in their vicinity, waiting for an errant stroke to send a ball sailing over the fence. When the facility’s tennis director, Laurence Alto, caught Braden trying to make off with one, he told him, perhaps with the hint of a smile, “You’re going to jail—or you’re going to learn this game.”

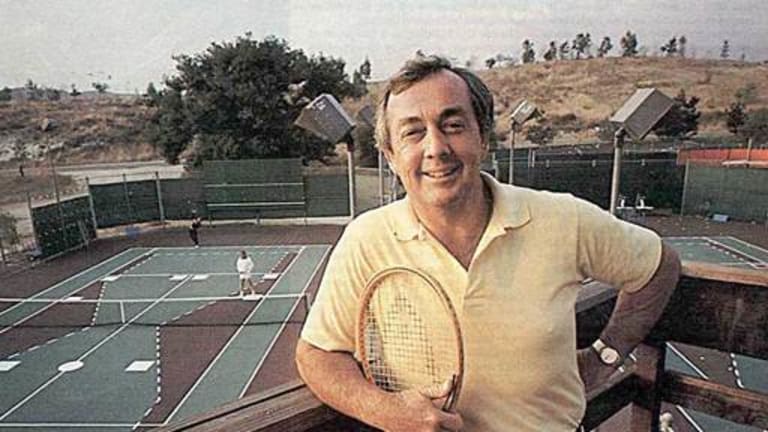

Braden, who died of a heart attack at age 85 this past weekend, would never stop learning this game. Even as his health declined in recent years, he was still trying to plumb the depths of the sport he loved.

“I can’t even tell you the number of projects he was working on,” his wife, Melody, told the Orange County Register in California, after his death. “That was him, though. He even wanted to start a new research project and I sat him down and asked him, ‘Vic, don’t you think you’ve researched every possible thing in tennis?’ He said no.”