He peaked as a player at No. 7 on the planet in 1990, advanced to the quarterfinals at both Roland Garros and the U.S. Open in 1989, and upended a cluster of big-name players over the course of his brief yet sparkling career, including Stefan Edberg, Mats Wilander, Boris Becker, Pete Sampras and Jimmy Connors. After serious knee issues curtailed his time in the pros in 1991, he soon established himself as an outstanding coach, and ever since has been one of the most respected individuals in that field.

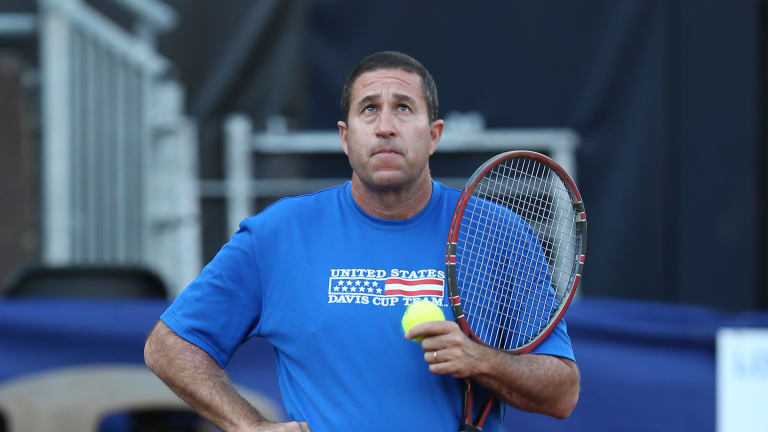

At the age of 51, Jay Berger can be certain that his reputation, as both a man and an unassailable professional, have been molded through decades of dedication to not only the sport, but the people who inhabit it. He has contributed to tennis on a multitude of levels, as a competitor of unimpeachable integrity, as a coach of the U.S. Davis Cup and Olympic teams, working with individual players, and serving from 2008-2017 as Head of men's tennis for the USTA Player Development program. And yet, after all he has done, regardless of his wide range of accomplishments, as prominent as he indisputably is, Berger now finds himself recognized even more for simply being the father of the widely admired professional golfer, Daniel Berger.

Jay is fine with that.

"Wherever I go now, I am known as Daniel Berger's father,” he says. “All of the questions go there—not about me, not about anything else, but about how Daniel is doing.

“It is really fun, and it has kept me connected to a lot of people. I love getting texts from people who I haven't talked to for a while. Daniel has huge support from the tennis community, who just love seeing him do well. Even the top players congratulate me on his success, which is really cool."

Gratifying as being the parent of a highly accomplished athlete from another sport surely is for Berger, tennis fans are nevertheless well aware of what he has achieved in his own right. Clearly, he might have accomplished even more if his knee problems had not forced him out of the game as a player at 25.

I asked Berger if he felt cheated that he needed to stop competing at such a young age.

"Actually, I was okay with it, because I had reached so many of the goals that I had,” he says. “I had done well. And I knew what I wanted to do afterwards, which was to coach.

“I would say the only thing that got me was that a lot of the reason I stopped playing was because I had a surgery that really took me out. It brought pain in my knee later on throughout my life. It was a shame about the tennis portion. I loved playing, but at the same time I could stop my career having accomplished quite a bit, and having no regrets on the way I went about my career. That made it palatable."