Opening the door—Thiem's US Open a sign of evolution in the men's game

By Steve Tignor Nov 17, 2020Eric Butorac will replace Stacey Allaster as US Open tournament director

By Associated Press Nov 17, 2025Beyond The Champions: 2025 US Open Winners and Losers

By Peter Bodo Sep 10, 2025In US Open defeat, Jannik Sinner faces his shortcomings

By Pete Bodo Sep 09, 2025Amanda Anisimova's US Open fortnight wasn't just "incredible"—it was redemptive

By Pete Bodo Sep 09, 2025Overcoming Doubt, Finding Deliverance: Six WTA takeaways from the 2025 US Open

By Joel Drucker Sep 08, 2025Service and a smile: How Carlos Alcaraz conquered Jannik Sinner at the 2025 US Open

By Steve Tignor Sep 08, 2025Carlos Alcaraz captures sixth Slam and second US Open title, dethrones No. 1 Jannik Sinner

By David Kane Sep 07, 2025Alcaraz vs. Sinner US Open final start delayed by 30 minutes

By TENNIS.com Sep 07, 2025Blinding Lights: Amanda Anisimova rues missed opportunities, serve woes after US Open final

By Stephanie Livaudais Sep 07, 2025Opening the door—Thiem's US Open a sign of evolution in the men's game

The Austrian’s title run at Flushing Meadows may not have signaled a changing of the men’s guard, but could it lead to a new, more egalitarian era in tennis?

Published Nov 17, 2020

Advertising

“Be careful what you wish for.” Dominic Thiem learned the wisdom of those words at this year’s US Open.

For the better part of a decade, the 27-year-old Austrian had looked forward to the moment when he would play for a Grand Slam title without having to beat either Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic or Roger Federer the ageless Big Three—to do it.

Thiem had put in the mind-numbing work on the practice court. He had thrashed a million tennis balls with his vicious, dive-bombing topspin. He had hot-stepped his way through countless footwork drills to try to make his legs a millisecond quicker. He had adjusted his clay-based game for hard courts. He had replaced his long-time coach with Nicolas Massu, an undersized Chilean who had made the most of his modest gifts and won two Olympic gold medals.

Nobody in the ATP worked out more relentlessly or competed more often than Thiem. Even during the lockdowns this spring, he found a way to play 30 matches, and he won nearly all of them.

In his three previous Grand Slam finals, Thiem had taken a small step forward each time. At Roland Garros in 2018, he lost to Nadal in straight sets. The next year, again at Roland Garros, he lost to Nadal in four sets. At the Australian Open in 2020, he lost to Djokovic in five sets. Finally, in his fourth major final, Thiem seemed to have caught a break from the tennis gods: Instead of one of the Big Three, he faced his friend Alexander Zverev, a 23-year-old who was making his major-final debut. Now, surely, Thiem’s time had come. The experts made him a solid favorite to win.

There was only one small problem: When he started the match, he could barely swing his racquet.

“I was super, super tight,” Thiem admitted. “I was tighter than in a long time. Didn’t even know how that feels anymore. Didn’t even know how to get rid of that.”

It turned out that being the favorite had its drawbacks. Serious ones.

“Maybe it was not even good that I played in previous finals,” he said. “I mean, I wanted this title so much, and of course, there was also in my head that if I lose this one, it’s 0–4.”

“Is this chance ever going to come back?” Thiem began to wonder as he fell further behind. “All these thoughts, which are not great to play your best tennis, to play free.”

Opening the door—Thiem's US Open a sign of evolution in the men's game

© Getty Images

Advertising

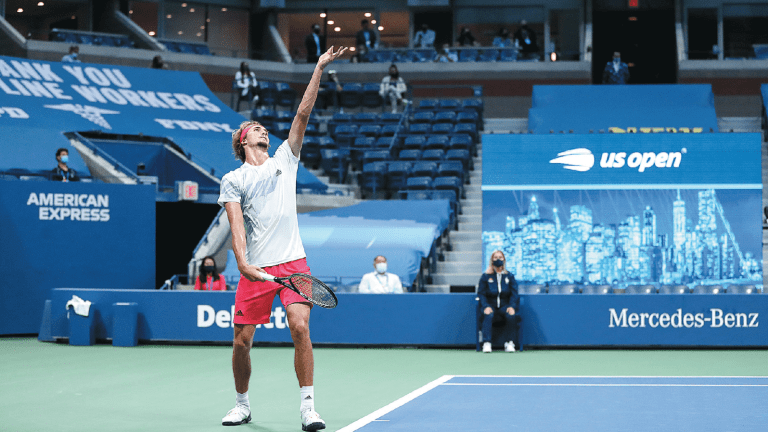

Thiem’s US Open win may not have signaled a changing of the men’s guard. (Getty Images)

Was Thiem, who had been on tour for nearly a decade, destined to be the Prince Charles of tennis, the man who was never allowed to be king? His saving grace, it turned out, was that Zverev was even more nervous than he was. Up two sets and a break, Zverev turned into the sport’s version of a deer in the headlights. While Thiem only played his best for a few games of the final, and he cramped near the end, he never stopped going for his shots. After four hours, it paid off with a breakthrough victory.

“I said to myself, I mean, I’m playing bad, I’m way too tight, legs are heavy, arms are heavy,” Thiem said. “Somehow the belief today was stronger than the body, and I’m super happy about that.”

Thiem’s win wasn’t just a personal milestone. It was a breakthrough for an entire generation—or more—of players who had been shut out of the majors, and had their career trajectories flattened by the Big Three. As of the start of Roland Garros in September, Thiem was the only male player under age 31 who had won a major title.

Was this the start of a new era, or was it a blip on the ATP radar screen? We had seen other one-off US Open wins before: Juan Martin del Potro in 2009, and Marin Cilic in 2014. Or was this final between two 20-somethings the start of a transition period, when the Big Three and the Next Gen will vie with each other for supremacy? Even Thiem didn’t seem sure.

“The question is,” he said, “how I’m going to [deal] with the emotions mentally. Obviously, I’ve never been in this situation. I achieved a big, big goal.” But just because Thiem achieved a big goal doesn’t mean Federer, Nadal and Djokovic are going to take their bows and cede the stage to him.

“We can talk about changing of the guards, but the Big Three aren’t going away anytime soon,” says Tennis Channel commentator Jan-Michael Gambill. “It’s amazing to say, since they’re in their 30s, but Nadal and Djokovic could both have five more good years in them.”

Opening the door—Thiem's US Open a sign of evolution in the men's game

Advertising

Unlike Thiem, Zverev was loose to start the US Open final. (Getty Images)

For tennis lovers of a certain age, the 2020 US Open brought back memories of Wimbledon in 1973. That year, 80 prominent male players, including the two most recent champions, Stan Smith and John Newcombe, boycotted the event over a political dispute between the newly-formed ATP and the sport’s old-guard amateur officials. With the game’s elite on the sidelines, 21-year-old Jimmy Connors and 17-year-old Bjorn Borg, neither of whom had gone deep at a Grand Slam before, lit up the All England Club with their brazen, youthful star power, and reached the quarterfinals.

The next year, Borg won his first Roland Garros, and Connors won his first Wimbledon and US Open. From 1974 to 1983, the Swede and the American won 19 majors between them. The boycott generation, meanwhile, had its last hurrah in 1975, when Arthur Ashe won Wimbledon. The boycotters opened the door, and Borg and Connors happily swaggered through it. They gained confidence at a major event without having to beat any top-ranked opponents to do it.

Is it possible that a similar door was opened—or at least cracked—at the 2020 US Open? Federer was absent due to injury; Nadal skipped the event because of travel and coronavirus concerns; and Djokovic took himself out of it when he hit a ball that struck a line judge. The result was a men's field that, for the first time in a long time, felt young again.

Of the eight quarterfinalists, six—Denis Shapovalov, Borna Coric, Andrey Rublev, Daniil Medvedev, Alex de Minaur and Zverev—were under 25. And that list didn’t include a number of young players, such as Stefanos Tsitsipas, Matteo Berrettini, Karen Khachanov, Felix Auger-Aliassime and Taylor Fritz, who are expected to challenge for big titles in the years ahead. Perhaps seeing one of their own hold up the winner’s trophy in New York will make them feel as if they could be in that position one day as well.

For Gambill, it isn’t the prospect of a changing of the guard that intrigues him. It’s the possibility that now, rather than total dominance by the Big Three, we’ll start to see a wider range of potential champions, as different generations and playing styles collide in the later rounds at the majors.

“To me, it’s an exciting time, and Thiem’s win was good for tennis,” he says. “You have so many different types of players and characters among the young guys.”

Opening the door—Thiem's US Open a sign of evolution in the men's game

© Getty Images

Advertising

Many feel Shapovalov's shot-making and charisma will make him a future star. (Getty Images)

Gambill points to Tsitispas, and especially Shapovalov, as players whose flashy game styles and charismatic personalities could draw young fans to the sport. “I’ve always been a big Shapo fan,” Gambill says of the 21-year-old Canadian. “He’s a fiery guy and a shotmaker. He’s got that X-factor, and a big upside.”

But if we’re looking for the new generation's Big Three, Gambill thinks that, at least for now, we’ll find it in Thiem, Zverev, and Medvedev.

“Those are the guys who have won week in and week out,” he says. “And we’ve seen them beat Federer, Djokovic and Nadal and reach Slam finals.”

Three-time Grand Slam doubles champion Mark Knowles agrees that Thiem’s breakthrough in New York wasn’t a one-off event.

“I know that once you win that first major, there’s a freedom that comes about,” Knowles says. “I think [Thiem]’s a warrior for winning the Open final with so much pressure on him. He’s always adding to his game, and now that he’s got the first one, I think he’s only going to get better.”

Like Gambill, Knowles sees the future of men’s tennis as a productive clash of top-level players, rather than a period that will belong to a single, dominant champion. Zverev, they believe, made new fans with his tearful post-match speech at the Open, which he dedicated to his absent parents. And the experience of having played and lost a major final, while painful, will be a valuable one.

“I really felt for him in his speech,” Knowles says of Zverev, “that feeling of not giving validation to his parents with a Grand Slam title. But that may drive him, and I think he'll have a long, successful career.”

Gambill also thinks that Zverev’s strong start in the US Open final can serve as a model for how he should play in the future.

“He knows he can go out and attack,” Gambill says, “and not just play a chess match out there.”

Opening the door—Thiem's US Open a sign of evolution in the men's game

Advertising

Getty Images

Despite Thiem and Zverev’s recent success, it’s Medvedev who many believe could change and advance the game with his disruptive tactics and deceptive playing style. The 24-year-old isn’t another baseline ball machine; instead, he plays with an always-surprising mix of grace and guile. The 6’6” Russian can lounge at the back of the court for a half a set, before leaping forward to pounce on his unsuspecting opponent.

With his long frame, and his ability to attack from deep in the court, Medvedev expands, elongates and complicates the game in a way no one else has before.

“He’s a great player, and an interesting player,” Gambill says of Medvedev. “He’s already come so far in such s short time, and really established himself as a consistent threat.”

“I love watching him,’ Knowles says. “He brings a completely different dynamic than anyone else. He’s smart, he can get emotional, he moves as well as anyone.”

Rather than heralding a revolution, Thiem’s US Open may be a sign of evolution in the men’s game. Ideally, it will begin to shift the tour from a three-man monarchy to a polyglot democracy, with representatives from Austria, Germany, Russia, Italy, Canada, Greece, the United States and Australia—as well as Spain, Switzerland, and Serbia.

“I had it in the back of my head that I had a great career so far, way better career than I could ever dreamt of,” Thiem said in New York. “But until today there was still a big part, a big goal missing.”

Thiem spoke for himself, but let’s hope his fellow 20-somethings believe he was also speaking for them. If Thiem can get what he wished for, maybe they can, too.