We moved offices at Tennis magazine last week, and as I was clearing out mine, I came across an original Prince Graphite in a pile of racquets. A few of us took turns twirling it and giving it a few shadow swings. The old-style leather grip felt raw but good. There was nothing soft or overly comfortable about it; you knew you had a weapon in your hand. The plain, dark, green-and-gold cosmetic was simple and striking compared to many of the splashier and gaudier color combinations we see today. I was confident that I could take it out on the court and it would play as well as anything made in the last year. The Graphite, used by Andre Agassi, Michael Chang, and Gabriela Sabatini along with many thousands of hackers, was one of the classic mid-80s frames that set the template for what has been made ever since. For all of the various nano-technologies and atomically altered materials of the ensuing decades, it was hard to improve on what Prince created with the Graphite.

It turned out that the company, the one most closely associated with the tennis boom, wouldn’t get back to its early peak. Prince, after changing hands among private-equity investors in recent years, filed for bankruptcy today. It has been scooped up by Authentic Brands, a “brand development” firm that also recently bought the rights to the image of Marilyn Monroe. ABG-Prince eventually plans to return as a “performance racquet” manufacturer. The company cited “increased competition” and the financial downturn as reasons for the decline. The two-decade rise of Babolat from string maker to racquet-making titan was the biggest of those new competitors. Prince was also hurt by the recession and flat tennis-equipment sales across the board. The company put money into developing its EXO3 technology and continued to try to sell its frames at high prices. Having its most famous endorser, Maria Sharapova, defect from an EXO3 Black to a Head frame in 2010 didn’t help, either.

Which is all a shame, because from start to finish Prince was an innovator. The company’s story is the story of the Open era. Founded as a ball-machine manufacturer in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1970, it was bought by Howard Head six years later. Head, the inventor of the aluminum ski, had taken up tennis in retirement and found it too difficult to play with the old small-headed wooden racquets. That was a common complaint, obviously, but Head was one of the first to try to do something about it. He designed the oversize aluminum Prince Pro, which began to appear, mostly to guffaws, at country clubs and newly built public courts in ’76.

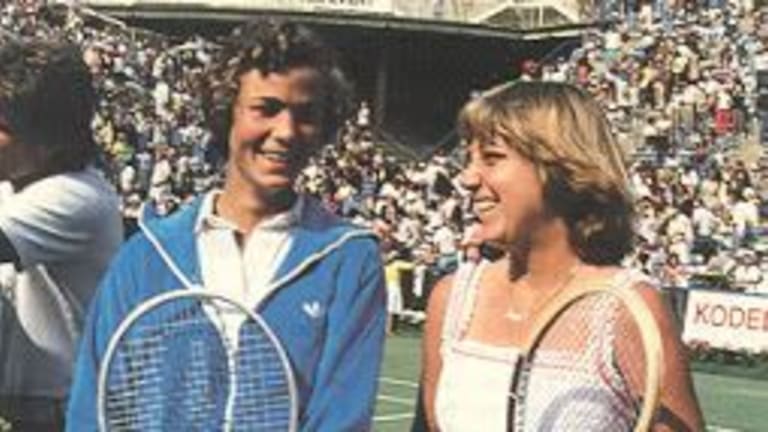

Here was a bizarrely futuristic physical manifestation of the tennis boom, an invention that helped the millions of new players trying to learn the sport, but which was dubbed a “cheater’s racquet” by traditionalists. Pam Shriver changed all of that when she reached the final of the U.S. Open as a Prince-wielding 16-year-old in 1978. The bigger sticks were here to stay, and the P logo became inescapable around the sport, a graphic symbol of its democratic new era. By the start of the next decade, Prince owned an astounding 30 percent of the U.S. racquet market. For all the talk we hear about spin-producing strings and ball-slowing surfaces today, that shift, to the bigger frame, is still the most seismic change of tennis's last four decades.

Today Prince could be said to represent something else. The demise, for now, of this classic American brand largely at the hands of a European company, Babolat, mirrors the general shift toward Europe—or at least out of the United States—in the sport at large. But Prince leaves a legacy of quality. The company was proud that they continued to put money into R&D, into trying to make their racquets better. At the same time, though, many consumers were drawn to the updated vintage frames that have been issued by Dunlop and Wilson in recent years. Prince wanted to push the EXO3.

Picking the Graphite up reminded me of the one time that I used it in a real match. In college my racquet of choice was the Sampras Wilson Pro Staff, but during a doubles tournament I broke the strings in all of the frames I had in my bag. My partner and I made the final, so I grabbed another teammate's Prince Graphite as I was walking onto the court. My first shots in the warm-up were the first shots I had ever hit with it. Do I need to tell you how this story turns out? I went on to play as well I’ve ever played in a doubles match, and we upset the top seeds for the title. Afterward, I handed it back to my teammate and said, “You can’t lose with this thing.”

For some reason, I never picked up the Graphite again. Brand loyalty is real, I guess, and I was a Wilson guy at the time. Now most young players I see are Babolat kids; with its simple but striking blue-and-yellow cosmetic and big-name endorser, Rafael Nadal's AeroPro Drive is the Graphite of the moment. Whatever the future brings, though, no racquet company had a bigger effect on the modern game, from top-ranked pros to rank beginners, than Prince.