Australian Open

Rafael Nadal and the definition of sacrifice

By Jan 24, 2023Australian Open

Australian Open prize money hits record high

By Jan 06, 2026Australian Open

Venus Williams will become oldest woman to compete in an Australian Open main draw with wild card entry

By Jan 02, 2026Australian Open

Roger Federer to headline “Battle of the World No.1s” at Australian Open’s inaugural Opening Ceremony

By Dec 11, 2025Australian Open

Australia at Last: Reflections on a first trip to the AO

By Jan 29, 2025Australian Open

Alexander Zverev must elevate his game when it most counts—and keep it there

By Jan 27, 2025Australian Open

Jannik Sinner draws Novak Djokovic comparisons from Alexander Zverev after Australian Open final

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Alexander Zverev left to say "I'm just not good enough" as Jannik Sinner retains Australian Open title

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Jannik Sinner is now 3-0 in Grand Slam finals after winning second Australian Open title

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Taylor Townsend and Katerina Siniakova win second women's doubles major together at the Australian Open

By Jan 26, 2025Rafael Nadal and the definition of sacrifice

A post-loss remark from Rafa last week is worth revisiting.

Published Jan 24, 2023

Advertising

Advertising

As always, Nadal tends to put things in proper perspective.

© 2023 Will Murray

Advertising

Advertising

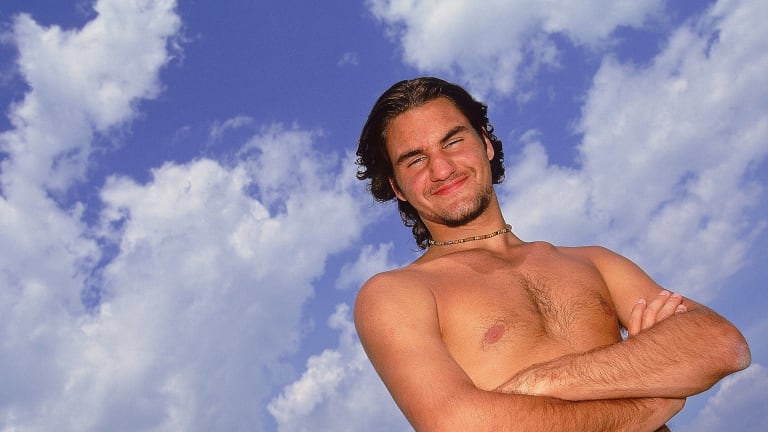

A teenage Roger Federer at a photo shoot in South Beach.

© Getty Images