Is there a moment from your sports-fan past that you wish you could take back? When you reacted to a loss in a way that makes you cringe now?

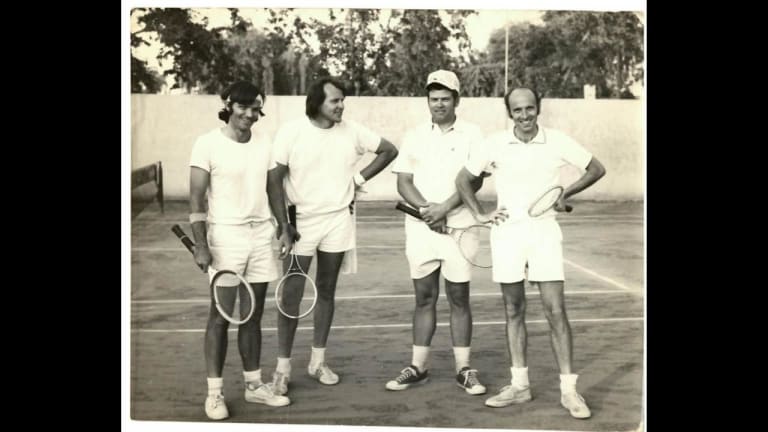

Mine came early, when I was 12. It was the July 4th weekend of 1981, and I was on the couch at a family gathering in Maryland, sitting next to my uncle Bob. (Pictured above, at far right.) We had just finished watching John McEnroe end Bjorn Borg’s five-year winning streak at Wimbledon. This was a crushing, traumatic blow for my sixth-grade self. Borg was my god. I had a Western grip, a two-handed backhand, and an uncomfortably tight pinstriped Fila shirt because of him. McEnroe, who would be my next god, was still vulgarity incarnate in my eyes. Surely, this grasping New York loudmouth couldn’t take the crown away from the beacon of gentlemanly perfection that was Borg? But this, of course, is exactly what happened, and Borg never tried to get the crown back. Nothing, I discovered, is perfect, not even the Angelic Assassin.