It’s time to retire the words “clay court specialist”

By May 25, 2022Was the Carlos Alcaraz-Jannik Sinner Roland Garros match the best ever played?

By Jun 13, 2025Who were the winners and losers at 2025 Roland Garros?

By Jun 09, 2025Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner played the match of the decade, and maybe the century, at Roland Garros

By Jun 09, 2025PHOTOS: Carlos Alcaraz captivates Chatrier with trademark joy after improbable Roland Garros title defense

By Jun 09, 2025Carlos Alcaraz saves three match points, tops Jannik Sinner in longest Roland Garros final of Open Era

By Jun 08, 2025Aryna Sabalenka clarifies controversial Coco Gauff claim: "Can't pretend it was a great day"

By Jun 08, 2025Coco Gauff counters Aryna Sabalenka's Roland Garros claim by saying she 'wanted' Iga Swiatek in final

By Jun 08, 20252025 Roland Garros men's final preview: Carlos Alcaraz vs. Jannik Sinner

By Jun 07, 2025PHOTOS: Coco Gauff celebrates Roland Garros title with parents, toasts champagne at Tennis Channel set

By Jun 07, 2025It’s time to retire the words “clay court specialist”

Modern tennis is largely shaped by the skill set it takes to currently succeed at Roland Garros: sharp-shooting accuracy, racquet head speed and aggression. If you can make it in Paris, you can make it anywhere.

Published May 25, 2022

Advertising

Advertising

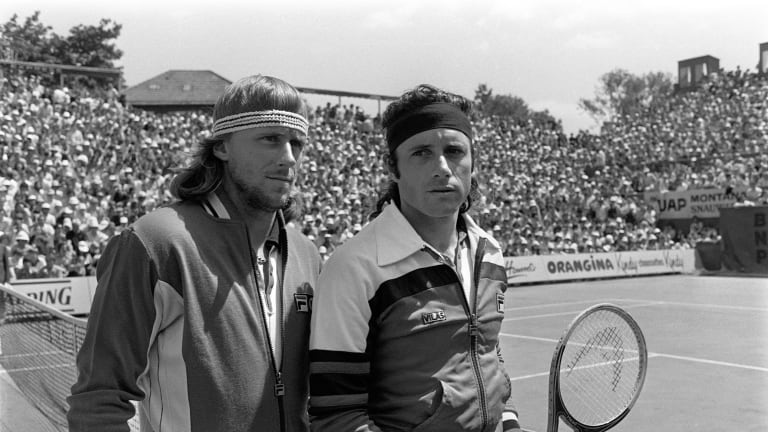

A remarkably low pulse, a two-handed backhand, an aptitude for hitting topspin higher than ever and two of the fastest legs in tennis history made Borg (center) a new kind of clay-court natural.

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

The first game of the 1978 final between Borg and Guillermo Vilas (right) featured two rallies north of 35 shots. Later came one 86 shots long.

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

Gustavo Kuerten, a free-spirited talent, arrived at Roland Garros in 1997 armed with a string that revolutionized tennis.

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

Sound as Nadal is at patrolling the court, he is a forthright aggressor on clay, keen to terminate rallies.

© 2005 Getty Images