We may never know who the world’s biggest Roger Federer fan is. To find this fervently and perhaps frighteningly devoted individual, we would need to survey the 14 million people who have made Federer their friend on Facebook, the 5.2 million people who follow him on Twitter, the 350,000 registered users at his website, rogerfederer.com, and the millions more who, as his opponents sometimes quietly complain, make the Swiss Maestro feel as if he’s playing tennis at home when he’s thousands of miles away from it.

We might also need to investigate Brazil. After visiting the country for the first time, in 2012, Federer told the Swiss paper Tages Anzeiger, “I met more fans that collapsed in tears than elsewhere. It was amazing how many were shaking. I had to practically take them in my arms and say, ‘It’s OK, it’s OK.’”

Yet even among that globe-spanning cross section of humanity, Michele Drohan, a Massachusetts native and Manhattan resident who has never set foot in Switzerland nor spoken with Federer face to face, says she “automatically wins any contest in which someone tells me they’re a bigger Federer fan.” Her trump card, you ask? The “RF” logo she has tattooed on the inside of her left wrist.

“I got it the day Fed won the French Open in 2009,” she says, while admitting that a celebratory beverage or two may have played a role in the decision. “My friends and family actually think it’s great, or so they say. Of course, there are a few people who think it’s nuts.”

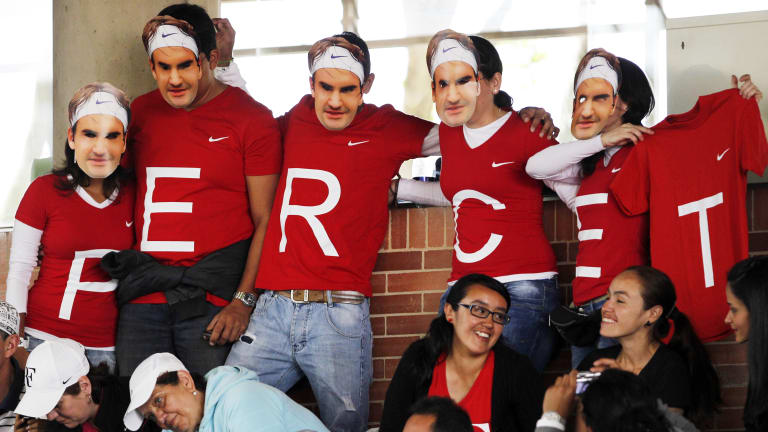

The tennis nut is not a new phenomenon, of course, but fans of today’s players have made the term seem more apt than ever. The sport’s current crop of likable, durable superstars—Federer, Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic, Ana Ivanovic, Serena Williams, Caroline Wozniacki and others—have inspired impassioned communities of followers on social media and given the game’s enthusiasts a new, collective, sometimes obsessive voice. Few, if any, sports are better suited to the Internet; in any given location, tennis fans may be sparse, but they can be found in virtually every country. And when it comes to the most famous player, Federer and his traditionalist appeal know no boundaries.

Just ask Colleen Taylor, who works in IT software in Dallas. Taylor has been a tennis fan since 1976, the year she turned on the Wimbledon final and caught a glimpse of Bjorn Borg and his long, blond hair flying across Centre Court. But her crush on Borg was just a warm-up for the deeper involvement with Federer, and his extended family of fans, that Taylor has developed over the last decade.

“I started to follow him when he won Wimbledon for the first time [in 2003],” Taylor says. “I thought, ‘This guy is different, the things he can do with a racquet, he’s a throwback.’ But it wasn’t until he lost to [Marat] Safin at the Australian Open in 2005 that I realized how much I cared. It was so devastating, and I thought, ‘Uh oh, I really like this guy.’”

Taylor knew the symptoms, and she knew where they would lead—to a lot more cleaning and a lot less eating.

“If Roger played an epic match every day,” she says, “I would be a size zero and my house would be immaculate. Watching on TV, I’m a wreck, and the commentary drives me crazy when he plays. I don’t know why, but I have to mute it. In the Wimbledon final [in 2014], I had to walk away completely.”

Taylor may have kept these facts mostly to herself, though, if she hadn’t discovered an online universe whose citizens knew exactly how she felt.

“It was nice to find a bunch of people who didn’t think I was crazy,” she says with a laugh.

Taylor’s virtual community soon became a real one, and she’s now something of a celebrity among the Federer faithful. She has met up with fellow Fed fanatics at ATP Masters 1000 tournaments in Indian Wells, Cincinnati and Miami, where she unveiled the first “shh!! quiet! genius at work” banners that can now be seen at virtually every Federer match, tucked into a (not-so-quiet) corner of the stadium.