Why did London swing, and not burn, that summer? Forbes’ description of the capital’s “happy irresponsible insanity” provides a clue: While the rest of the world may have been coming apart, this time the British didn’t have to hold it together.

By 1967, the British Empire had been contracting for 40 years. At its peak in 1922, it covered a quarter of the earth’s land mass. During the long period of Pax Britannica—“British Peace”—the Empire served as the world’s policeman. But after World War II, and America’s victories in Europe and the Pacific, that role had gradually been assumed by the U.S.

In 1960, Britain ended its national service requirement—the equivalent of the draft—for young men. In 1965, Winston Churchill, living symbol of the Empire, died at age 90. “Now Britain is no longer a great power,” Charles de Gaulle said upon hearing the news. Finally, in 1967, prime minister Harold Wilson “gave up on the remnants of Pax Britannica,” according to TheNew Yorker, by pulling British forces out of the Persian Gulf and the Pacific Rim. “That retreat handed responsibility for security in the Gulf...to the United States.” The world had a new sheriff.

As politics went, so did sports. In the 19th century, England spread its homegrown leisure activities—soccer, cricket, rugby, lawn tennis—across the Empire, and maintained control of them in the 20th century. Since 1939, tennis’s ruling body, the ITF, has been headquartered in London. For decades, one of its primary functions was to define and defend amateurism in tennis.

The amateur ideal, which made the sport an aristocratic pursuit, was another export of the British Empire. But the U.S. never had a deeply rooted leisure class, and an alternative to amateurism eventually arose here. In 1926, promoter C.C Pyle signed Suzanne Lenglen to play on the first pro tour. In the 1940s and ‘50s, Jack Kramer continued Pyle’s quixotic attempt to professionalize tennis. But it wasn’t until the 1960s that a group of U.S. team-sports promoters mounted a full-scale American invasion of tennis.

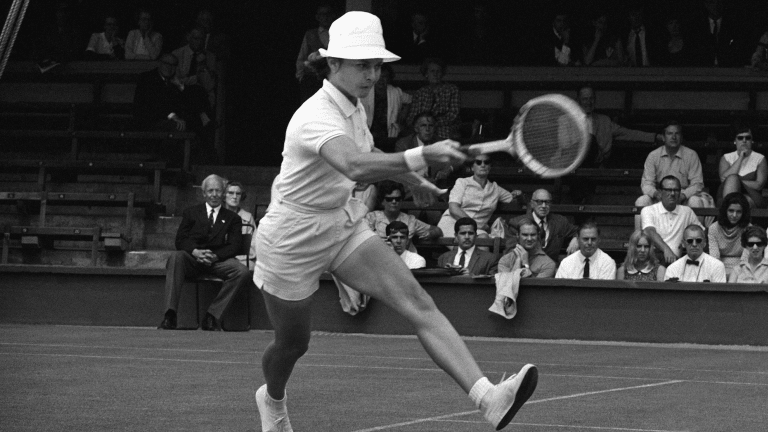

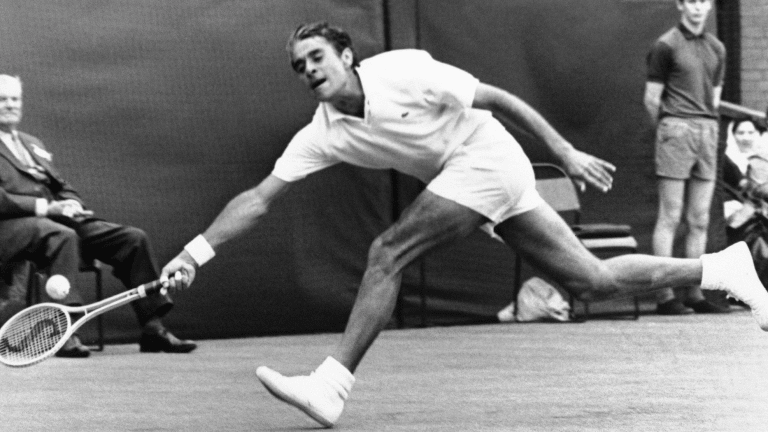

Lamar Hunt, owner of the Kansas City Chiefs, organized the WCT. George MacCall, a Las Vegas impresario, signed Laver and Billie Jean King to a rival pro circuit. Dave Dixon, founder of the New Orleans Saints, created the Handsome Eight. When Dixon poached John Newcombe, champion at Wimbledon and Forest Hills, the All England Club finally waved the white flag for amateurism. In 1967, while Harold Wilson was ceding Britain’s role as global policeman to the U.S., Herman David of the AELTC was surrendering control of tennis to the Americans.

The biggest story of Wimbledon in 1968 was its acceptance of professional players. But it was the access granted to another type of pro—the American hustlers looking to get a piece of the Open-era action—that would prove more significant. Along with the game’s superstars, Wimbledon also welcomed super-agent Mark McCormack and his company, IMG, inside its ivy-covered walls.

“Mark the Shark” knew what to do when he got there. He was a fast-moving, forward-thinking lawyer from Chicago who had, with his first star client, Arnold Palmer, pioneered the concept of the athlete endorsement. When he turned his attention to tennis, he brought a less romantic—and more American—view of the sporting world with him. “Fans do tend to be children,” McCormack told Sports Illustrated. “They try to pretend the athlete of their fancy is out there doing what he excels at for some greater good or glory than a buck.” To McCormack, players were “pawns in the massive, changing, vigorously competitive arenas of advertising and marketing.”

McCormack first visited Wimbledon in 1966, and was less than impressed with its organization. In ’68, he set about rectifying that. He negotiated the tournament’s TV contracts, provided corporate hospitality services, and helped sign Rolex as a sponsor. Soon McCormack represented Wimbledon, the BBC, WCT, the USTA, Laver, Newcombe, King, Chris Evert, Bjorn Borg and Bud Collins, among many others.

During the amateur era, tennis’ ruling body was the ITF; during the Open era, its ruling body would be IMG. Tennis was part of the American Empire now.