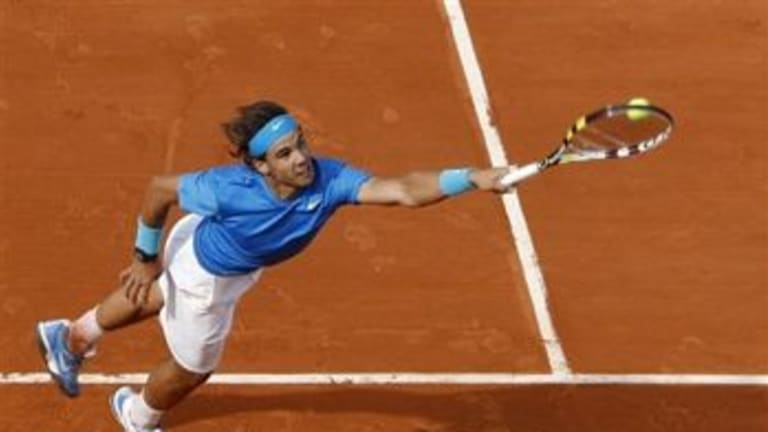

PARIS—It didn’t feel like an upset day. The sun was bright but not hot, the clouds were high and thin. There was nothing ominous, nothing dark or fierce or unsafe, in the air inside Court Philippe Chatrier. Maria Sharapova made quick work of her opening opponent, and when Rafael Nadal wrapped up the first set against John Isner without even having to go to the obligatory tiebreaker, it seemed that the one potentially tricky first-rounder for a top male player would be handled in routine fashion. Once Nadal had a break, he relaxed and snapped off a winning backhand pass, a shot that’s usually a harbinger of good things for him. If he’s hitting that one, you know he’s playing well.

But Isner is the kind of player who never allows you to relax, and that goes double for Nadal, who gets jumpy against the towering servers. He barely escaped Ivo Karlovic at Indian Wells this year, and Isner took a set from him in the same place in 2010. As Nadal said afterward, it isn’t just the power of these guys that makes them difficult to play, it’s the lack of rhythm you get from one point to the next, the unique trajectory from which they hit the ball, and the patience required to forget about the break point chances that they can blow away with one big swing of their racquets.

Nadal broke in the second, but when Isner broke back, he said he finally began to feel comfortable. Nadal went in reverse. The nerves crept back in with each game that went by, and each half-chance to break that he couldn’t convert. It was the backhand in particular that tightened up. At one point late in the second, I wondered, not for the first time, how Nadal has managed to do all he has with such an unnatural stroke on that side. In reality, he’s a man of two backhands, and he showed off that shot at its absolute best and worst this afternoon.

Most players, even the best players, have one shot that isn’t immune to nerves; if you didn’t, you might never lose. With guys who use two-hands, like Novak Djokovic, it’s usually the forehand that goes awry at the wrong time. With Nadal, it’s the backhand. His forehand can land short if he’s nervous, but it’s an extremely safe shot in general. With the topspin he generates, he can be confident that he can swing out and still get the ball to drop in. Nadal’s margin for error is much smaller on his backhand. Even when it’s at its peak—think 2008 Wimbledon final, and last year’s U.S. Open—it’s a line drive that requires a combination of blind confidence and nerveless precision. Those are two things, obviously, that you can’t call upon at will.

Isner attacked the backhand when he was down break points, and Nadal netted it over and over. By the start of the tiebreaker, the nerves had infected his forehand. He began by, to his obvious disbelief, sailing two very routine shots from that side over the baseline. Nadal later said that he played “too nervous” in the breakers, but it appeared to me that he had misjudged how far the livelier Babolat balls would carry—he really did look like he couldn’t believe it. Afterward, he was asked what he thought of the new balls. Nadal, a Babolat endorsee, was politic: “These balls are better for me, but it’s a very dangerous ball.” Arriving later than usual after the Rome and Madrid double, he hadn’t taken enough time before the tournament to get used to them.

After the second set, it was still bright and cool inside Chatrier, but there was upset in the air—Isner was, when you thought about it, just the kind of guy to pull off a one-shot like this. By the middle of the third, he was playing some of the best, and most appealing, tennis I’ve seen from him. He said he “began to strut” out there, and there was a sense of freewheeling enjoyment coming from him. He kicked the ball so high that Nadal was virtually hitting backhand overheads to return it. He got on top Nadal’s short returns with heavy topspin forehands, and he even closed out a particularly good service game with two delicate carved drop volleys—a strutting shot. The crowd, which likes Rafa but has never fallen for his aggressively physical style (the way they did for the elegance of Federer, the bohemian free spirit of Kuerten, and even the crassly effervescent panache of the early Agassi), embraced Isner happily—the many cries of “Allez, John!” had a pleasingly incongruous ring.

But then Nadal decided he couldn’t lose, and Isner decided . . . the same thing. Nadal stopped making errors, literally—he had zero in the fourth set. He served brilliantly and played with maximum efficiency. Afterward, Isner went so far as to say that Nadal’s play in the last two sets was the best he’d ever witnessed: “I haven’t seen tennis like that, ever.” I thought that Nadal was actually helped when he received a time-violation warning; from that point on, he played more quickly—he even urged the ball boys to get him the balls faster—and gathered momentum doing so. In the fourth, he played with something that he rarely plays with: dispatch. By the end of it, he had turned that bi-polar backhand around. Now he was loose and hammering it like a right-hander’s baseball swing.

It was on to the fifth, and maybe it was being in the arena and feeling that unique sense of anticipation as two players line up for the decider, but I was reminded that a fifth set remains one of the great events in sports. A test of endurance and nerve in equal measure, it comes from another era with a different sense of time, and it inject tennis with a sense of the epic. Boris Becker never said, as we think he did, "the fifth set is all about heart." He said it was all about "nerves." But we persist in believing that he said that former, not just because it sounds better, but because it might even be truer as well.