In the wake of the news that this week will mark the first in ATP history that no players in the Top 10 possess a one-handed backhand, Tennis.com offers a look back at a 2023 series counting down the 20 most impressive one-handers, and how their combination of beauty and efficiency left their mark on the game.

Special Feature

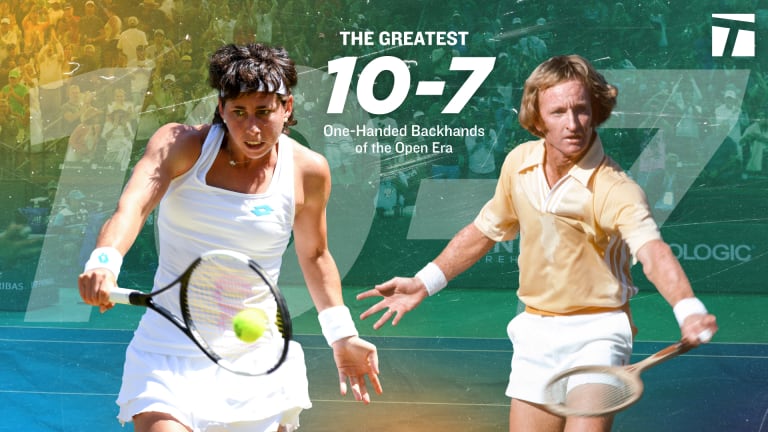

The Greatest One-Handed Backhands of the Open Era, Nos. 10-7: Ashe, Edberg, Suarez Navarro, Laver

By Mar 10, 2023Special Feature

The mindset of a super squad: How Danielle Collins, Emma Navarro and Tommy Paul became U.S. tennis stars

By Oct 30, 2025Special Feature

The mindset of a disruptor: Daniil Medvedev and Jelena Ostapenko harness the chaos

By Oct 29, 2025Special Feature

The mindset of a finalist: Sinner, Pegula and Zverev on what gives them a mental edge

By Oct 28, 2025Special Feature

Fifty years after winning her first US Open, Chris Evert says her legacy won’t be contained in a trophy case

By Sep 05, 2025Special Feature

Welcome to Tennis Channel Airlines ✈️

By Jul 15, 2025Special Feature

Henry Searle, 2023 Wimbledon boys' champ, trusts self-improvement mindset will see things fall into place

By Jun 29, 2025Special Feature

On the first day of the Paralymics in Paris, an ode to wheelchair tennis

By Aug 28, 2024Special Feature

What “gift” each American men's contender needs to get over the Grand Slam hump

By Mar 03, 2024Special Feature

One-Slam Wonderful: Yannick Noah's Roland Garros title, 40 years later

By Jun 11, 2023The Greatest One-Handed Backhands of the Open Era, Nos. 10-7: Ashe, Edberg, Suarez Navarro, Laver

This foursome hit with elegance and excellence.

Published Mar 10, 2023

Advertising

Advertising

At 4-4 in the fourth set of the 1975 Wimbledon final against Jimmy Connors, Ashe delivered the title-winning knockout blows with two screaming backhand winners.

© Getty Images

Advertising

Advertising

Edberg’s one-hander unlocked his net game, and made his transition into the backhand volley easier. Once there, he was second to none.

© Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Advertising

Advertising

As aesthetics go, Suarez Navarro's backhand might be No. 1.

© 2018 Getty Images

Advertising

Advertising

With his long extension and trunk-like left forearm, Laver could drive the ball and hit it with more topspin than most of his contemporaries.

© Getty Images