Tighten it up, tennis: present a united front, empower chair umpires and rework the rules

By Feb 01, 20232025 Year In Review

WTA Match of the Year, No. 5: Madison Keys topples Iga Swiatek in dramatic Australian Open semifinal

By Dec 09, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Following in family footsteps, Elli Mandlik clinches Australian Open return in wild card play-off

By Nov 25, 2025Social

“I can’t do another surgery”: Nick Kyrgios opens up on retirement plans

By Oct 16, 2025The Business of Tennis

Carlos Alcaraz adds $1 million Australian Open ‘one point’ challenge to packed schedule

By Oct 09, 2025The Business of Tennis

Top ATP, WTA players push Grand Slams again in bid for more money and more say

By Sep 24, 2025Facts & Stats

What a trio! Carlos Alcaraz, Iga Swiatek, Jannik Sinner to all chase Career Grand Slam in 2026

By Jul 13, 2025Pop Culture

Strive to survive: Film shows the pressure ball kids face to earn an Australian Open spot

By Apr 11, 2025The Business of Tennis

Top ATP, WTA players pen letter to Grand Slams seeking greater share of revenue

By Apr 04, 2025Lifestyle

Where is Madison Keys keeping her Australian Open trophy?

By Mar 06, 2025Tighten it up, tennis: present a united front, empower chair umpires and rework the rules

The sport seems to have outgrown its roots, yet tries to operate under values it has left behind.

Published Feb 01, 2023

Advertising

Murray finished off Kokkinakis at 4:06 a.m.

© Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Advertising

The tours haven't been in China since 2019. That year, the WTA Finals debuted in Shenzhen.

© Getty Images

Advertising

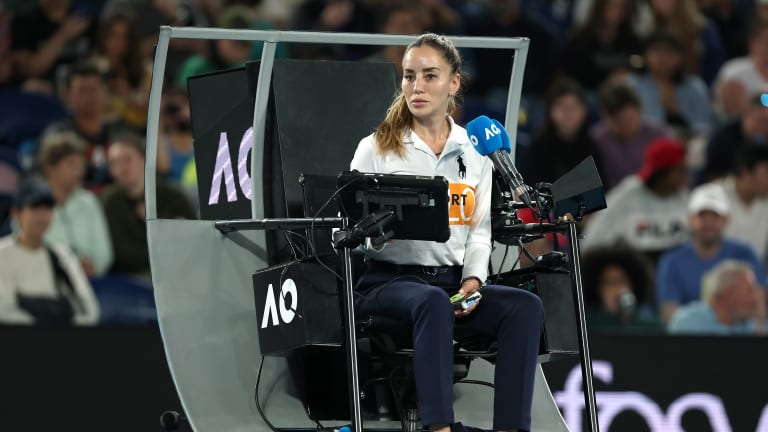

Chair umpire Marijana Veljovic looks on while overseeing this year's Australian Open meeting between Rafael Nadal and Mackenzie McDonald.

© Marc GIAMMETTA

Advertising

Chardy in discussion with chair umpire Miriam Bley during his eventual loss to Evans in Melbourne.

© Getty Images