“I call it Norman,” Roger Federer told The New York Times. “I’ve had dinner with Norman, spent a lot of time with Norman.”

Who is Federer’s new friend? “Norman,” in reality, is the replica of the Australian Open champion’s trophy that he won earlier this year, and which he has turned into a regular traveling companion. Norman accompanied Federer on a trip to a mountain chalet in Switzerland, and appeared with him in a GQ spread. “I know it’s super cheesy,” Federer said to the Times, “but the fans just love it.”

Federer has obviously reveled in his first Grand Slam title in nearly five years. But the fact that he has done it with this particular piece of hardware may be more appropriate than he realizes. The Australian Open men’s singles trophy is officially known as the Norman Brookes Challenge Cup. Its namesake wasn’t just the first great Aussie tennis champion, he was, in many ways, the Federer of his day.

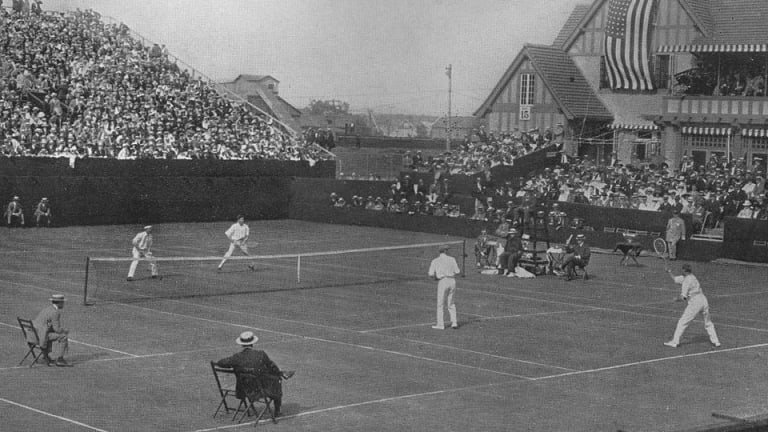

A native of Melbourne, Brookes had tennis in his blood. He was born in 1877, the same year that Wimbledon began hosting an annual tennis tournament. Known as The Wizard, Brookes could, as his friend and Davis Cup teammate Tony Wilding said, “Make the ball talk.”

“As a left-hander possessed of consummate concentration, a tenacious will to win, uncanny anticipation and a deft touch at net,” tennis historian E. Digby Baltzell wrote of Brookes in 1994, “he was apparently quite like our own John McEnroe.”

If Baltzell were writing today, he might have compared Brookes to “our own Roger Federer” instead. And he might have noted one more similarity between the two men: Their remarkable longevity.