The Swede and the American had something else in common: At the time there was some doubt about whether these two blond teens could back up their style, and their stardom, with substance. Borg and Evert had each taken the game by storm in their international debuts. Evert’s came at the 1971 U.S. Open, where, as a 16-year-old, she reached the semifinals and was dubbed, among other nicknames, Chris America and The Little Ice Woman. In 1973 at Wimbledon, Borg, dubbed the Teen Angel, took advantage of a boycott by the top players to secure a place on Centre Court for his first match. Mayhem ensued. For the better part of two weeks, he was chased off that court, around the grounds, and back to his hotel by packs of teenage girls. Tennis had experienced its first Borgasm.

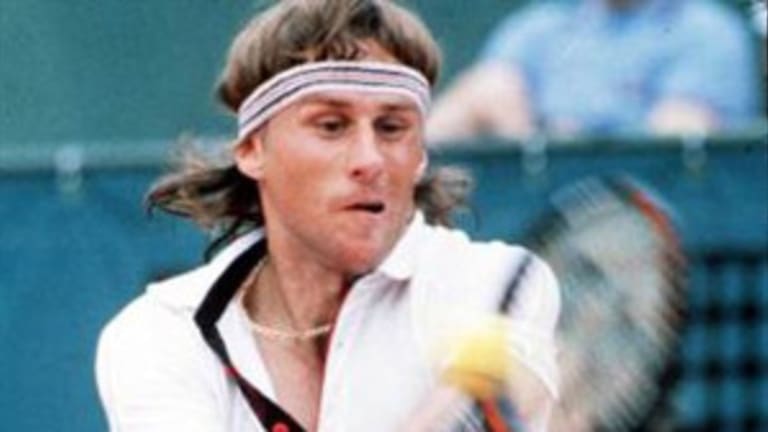

The Ice Woman and the Ice Borg were the new faces of a suddenly booming and sexy sport. Were they champions as well? By ’74, it had been three years since Evert’s promising debut. As for Borg, he had earned a reputation for pulling the ripcord in matches when they weren’t going his way. Were they spoiled by easy early money? Did they have the stomach to stand up to the old guard? Were they a little too icy for their own good?

All of those questions were answered in Paris in ’74. Evert, who grew up on green clay in Florida, showed that her baseline style worked to perfection on the slow red stuff in Paris. She didn’t drop a set in the event, and, in a Cold War blowout, she rolled over the Soviet Union's Olga Morozova 6-1, 6-2 in the final. (She and Morozova put politics aside to win the doubles.) Chrissie was just getting started. Despite skipping the French from '76 to '78—three years in which she was world No. 1—she would go on to win the tournament seven times. From '73 to '79, she would win 125 straight matches on clay. Take that, Rafa!

Borg also won in what would become his characteristic fashion. Four times his matches went the distance at Roland Garros that year. In those days, the men played two-of-three sets in the first two rounds; that spelled immediate danger for Borg, the most notorious slow starter in the game's history. He dropped the opening set to his first-round opponent, Jean-Francois Caujolle, before coming back to win 6-4 in the third. In the fourth round, Borg went down 0-6 in the first to Eric van Dillen before winning in five. In the quarters, he dropped the first 2-6 to Raul Ramirez before winning in five. And in the final, Borg topped himself by losing the first two sets before winning the last three 6-0, 6-1, 6-1. Orantes, a smooth-slicing Spanish lefty, was left stunned by the turnaround. No one would be stunned by a Borg comeback again. Ice had been in Borg’s stomach all along.