Remembering Arthur Ashe as both a champion and an intellectual

By Steve Flink Feb 20, 2019French Open to reveal second retractable roof court at Roland Garros ahead of Olympics

By Associated Press Apr 25, 2024Your Game

Geared Up: Rafael Nadal plays out his illustrious career with Babolat and Nike

By Baseline Staff Apr 25, 2024Madrid, Spain

China's Wang Xinyu saves 10 match points in first-round Madrid win over Viktoriya Tomova

By TENNIS.com Apr 24, 2024Pop Culture

Review: Plenty to be excited about in TopSpin 2K25, which successfully recreates the joy (and frustration) of tennis

By Stephanie Livaudais and Spencer Thordarson Apr 24, 2024Madrid, Spain

Fabian Marozsan saves 11 set points, wins pair of Madrid tie-breaks to defeat Aslan Karatsev

By TENNIS.com Apr 24, 2024Pop Culture

Coco Gauff dishes on 'embracing adulthood' in TIME magazine's May cover story

By Baseline Staff Apr 24, 2024Pick of the Day

Roberto Carballes Baena vs. Dominik Koepfer, Madrid

By Zachary Cohen Apr 24, 2024Madrid, Spain

Caroline Wozniacki stumbles in clay comeback, exits Madrid in nostalgic Errani match

By David Kane Apr 24, 2024Madrid, Spain

Rafael Nadal says he is not 100% fit ahead of Madrid debut and unsure about playing Roland Garros

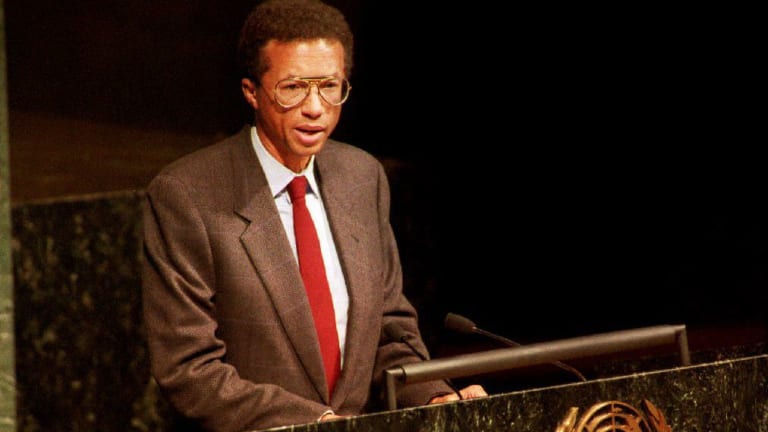

By Associated Press Apr 24, 2024Remembering Arthur Ashe as both a champion and an intellectual

With February being Black History Month, it's only fitting that we focus on all of Ashe's amazing accomplishments.

Published Feb 20, 2019

Advertising

For more than half a century, first as a fan and later as a reporter, through all my years in and around the world of tennis, I have never known a more estimable individual than Arthur Ashe. He was much larger than the game he played for a living. Multi-faceted, agile of mind and stout of heart, his curiosity about so many avenues in the lanes of life was boundless. His intellectual firepower was astonishing.

Considering that Ashe had such a wide range of interests and an immeasurable thirst for knowledge, it is all the more remarkable that he accomplished so prodigiously across his lifetime. Ashe was victorious at the first US Open in 1968. He triumphed at the Australian Open two years later, played on three consecutive winning American Davis Cup contingents from 1968-70, and capped his career substantively and stylishly by toppling the heavily favored Jimmy Connors to rule at Wimbledon in 1975. Although Connors was recognized officially as the top-ranked player in the world on the ATP computer that year, Ashe was the preeminent player in the hearts and minds of most erudite observers. The experts predominantly placed him at the top.

His achievements must be admired even more because of the extended battles he fought as an African American athlete breaking down barriers in a sport populated overwhelmingly by whites. To be sure, Althea Gibson had paved the way significantly for Ashe with her exploits over the course of the fifties, taking the French Championships in 1956, capturing Wimbledon and the US Championships in 1957 and 1958. Gibson was the first African American to get on the board at the majors, but the fact remained that Ashe had to bear a lot of burdens along his journey to greatness. He did it all with immense grace, uncommon decency and high intelligence.

I met Ashe briefly at the US Open in 1972, when I was working as an “aide de camp” for Bud Collins. The Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) had just been formed, and Ashe, who would take over as president a few years later, was one of the original officers.

Only a small group of reporters was assembled in a room beneath the stadium at the West Side Tennis Club for the ATP announcement, and I was there representing Collins at that press conference. Near the end, the British reporter Richard Evans left, thinking it was over. Ashe noticed the departure of Evans, and asked me to chase Evans down and bring him back, which I did. Ashe was making a strong and inspired bid to win a second US Open title, upending Wimbledon champion Stan Smith in the quarterfinals, removing countryman Cliff Richey in the penultimate round, and facing Ilie Nastase in the final.

Against the rambunctious Romanian, Ashe led two sets to one and 4-2 in the fourth set but, with Nastase acting out abominably and distracting the American with his antics, Ashe lost in five tumultuous sets. Afterwards, the stoical and imperturbable Ashe uncharacteristically displayed his emotions, sitting in a chair at the far side of the stadium, holding his hands over his eyes, and crying. I was only 20 at the time, and just making the difficult transition from fan to reporter. Distraught about Ashe’s missed opportunity, I walked to the clubhouse and found a quiet corner to shed a few of my own tears.

Four months later, I had my first interview with Ashe during a tournament at the Albert Hall in London. He was cordial and respectful, but I have no doubt in retrospect that he surmised I was a nervous young reporter. Nonetheless, he spoke freely about tennis politics, the USTA, the state of the game, and a wide range of matters. Then I asked him if he still reflected on his agonizing defeat against Nastase at the US Open.

Having observed him from a distance, I was surprised about what I heard from Ashe up close.

He looked me directly in the eye and said, “I think about it all the time. Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night thinking about that match. If I had held my serve two more times in the fourth set, I would have had my second US Open title.”

After Arthur Ashe captured the @USOpen title in 1968, the first African-American man to win a major, he founded the NJTL with Charlie Pasarell & Sheridan Snyder, supported by the #USTAFoundation, reaching over 200,000 youth today in tennis, education, & character development. pic.twitter.com/ryZOeEs8tE

— USTA (@usta) February 20, 2019

Advertising

That was an important interview for me, and a significant step in my career. I had established myself in at least a small way with Ashe, and was now on his personal radar screen. In the years to come, I would get to know him well, interviewing him frequently, crossing paths with him in many different settings. I never ceased to be amazed by the acuity of his mind, and the strength of his convictions. Not only did he seem larger than the game, but—at least in my view— he was larger than life.

Our interaction occurred regularly over the years. A few months after his widely celebrated Wimbledon triumph in 1975, I flew down for an eight-player tournament in Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, where Ashe was one of the participants. Landing in Savannah, Georgia, I ran into Ashe at the baggage claim, and we shared a car ride over to Hilton Head. I would conduct a formal interview with him a few days later, but now, on this sunny Sunday afternoon, he held court with me off the record. We spoke about a player who shall remain nameless. He had caused some trouble with his fellow competitors that year. Ashe had just played this guy recently, and was appalled by some of the behavior he had witnessed.

He told me, “If his father knew half of the horrendous things that this guy has done these last few years, I believe he would disown him.”

The following year, we were both at a New York gathering for Sargent Shriver, a friend of Ashe’s who was running for President. I spoke with Ashe about the renowned commentator Howard Cosell, with whom he worked on ABC. I asked him why he believed Cosell sometimes evoked such irrationally negative reactions to his work from the public.

Ashe unhesitatingly responded, “I think a lot of it is anti-Semitism. I can’t come up with a better explanation.”

Not much later, I found myself in Ashe’s New York City apartment. I was working for World Tennis Magazine and was accompanying the art director on a photo shoot. That gave me a chance to converse casually with Ashe on topics ranging from his Achilles heel injury, to the rise of Bjorn Borg, to the decline of Rod Laver. Through it all, we sipped orange juice and listened to Stevie Wonder on his stereo system. I was relaxed and congenial. An hour went by rapidly.

There are countless other examples of Ashe’s wit, wisdom and sense of humor that I experienced over the years. In 1977, I saw him at the Orange Bowl World Junior Championships in Miami Beach, not long after Ivan Lendl had come from behind to beat Yannick Noah in the final. Ashe had been an invaluable ally to Noah from the time the Frenchman was 10 years old. Noah had been in a position to finish off Lendl but had squandered it.

Ashe told me, “He just has to learn how to close out matches like that. It isn’t easy. Yannick will figure it out. He just got flustered.”

A few years later, at his last Wimbledon in 1979, I was walking through the locker room with John Barrett of the BBC, and there was Ashe by his locker, getting ready for his match.

“Hey, Steve,” he said. “I just recently met your father.” I asked him where and he replied, “I can’t tell you where it was, but I know it was your father!”

We both laughed heartily.

Remembering Arthur Ashe as both a champion and an intellectual

© AFP/Getty Images

Advertising

But my two most enduring memories of Ashe were of rides we shared both to and from New York City. In late 1986, he drove me from Madison Square Garden to my home in Westchester County, New York. He lived about five minutes away from me at the time. On that trip, we spoke about everything from world politics to tennis commentators to just about everything happening in the world. He was an outstanding conversationalist.

A few years later, we were on a train into the city, and sat together for an hour discussing college sports, tennis, football and even the world of entertainment. The subject turned to Chrissie Evert. She was then No. 3 in the world after a long stint at No. 1 and then five years in a row at No. 2 behind Martina Navratilova. She was coming under criticism in some quarters for the slight dip, which struck Arthur as absurd.

“Who wouldn’t want to be the third most highly regarded doctor or lawyer or writer?,” he said. “Why can’t people understand that No. 3 is damned impressive? The critics should leave Chrissie alone. She’s doing fine.”

All through his life, right up until his death at the age of 49 in February of 1993, Ashe was a champion of the human spirit, and a man of immense stature. As we celebrate Black History Month, many memories of Arthur Ashe flood into the forefront of my mind. But perhaps my favorite recollection is of an interview I did with him once for World Tennis Magazine reflecting on his landmark Wimbledon triumph in 1975.

Putting that win over Connors in perspective, he said, “Winning Wimbledon provided a very satisfying capstone to my career. I felt against Connors that it was in the cards. The gods had ordained it. That was the way it was supposed to be. It was divine intervention. I was playing in the zone, on the right side of my brain— which is creative and mystical.”

So many sports fans were overjoyed by Ashe taking the premier title in tennis, and they would convey that to him wherever he went.

As he told in the mid-1980’s, “I might be standing in an elevator or walking down the street, and somebody comes up to me and says something about it. Among whites, they say it was one of their most memorable moments in sports. Among blacks, I’ve had quite a few say it was up there with Joe Louis in his prime and Jackie Robinson breaking in with the Dodgers in 1947. I would say it happens once a month someplace.”

Ashe would be 75 if he were alive today. He passed away four years before the new stadium at the US Open named after him came into view, leaving us far too soon. I think about him often, and believe that the tennis world would be a much loftier place if he were still among us.

Advertising

ATP Rio De Janeiro

• Starting Monday 2/18, at 2:30 pm ET, catch live coverage of the Rio Open featuring Dominic Thiem, Fabio Fognini, and Diego Schwartzman.

WTA Dubai

• Watch Naomi Osaka, Petra Kvitova, Simona Halep and Karolina Pliskova live from the Dubai Duty Free Tennis Championships starting Saturday, 2/16 at 3:00 am ET

WTA Budapest

• Tennis Channel Plus features live coverage of the Hungarian Ladies Open beginning Monday, 2/18 8:00 am ET

ATP Delray Beach

• Watch Juan Martin del Potro, John Isner and Frances Tiafoe live on Tennis Channel Plus beginning Tuesday, 2/19 at 12:30 am ET.

ATP Marseille

• See Karen Khachanov, Borna Coric and Stefanos Tsitsipas live on Tennis Channel Plus beginning Monday 2/18, 8:30 am ET