In Memoriam: Pancho Segura, Vic Braden, Dennis Van der Meer

By Joel Drucker Dec 13, 2019Madrid, Spain

Carlos Alcaraz begins Mutua Madrid Open title defense, defeats Alexander Shevchenko

By David Kane Apr 26, 2024Defending champion Sabalenka advances at Madrid Open with a 3-set win over Linette

By Associated Press Apr 26, 2024Pop Culture

New movie Challengers asks: Where does tennis take us?

By Joel Drucker Apr 26, 2024Madrid, Spain

Aryna Sabalenka defeats Magda Linette, begins Mutua Madrid Open title defense

By David Kane Apr 26, 2024Social

Shelby Rogers dishes on the viral social media video that went all the way to Will Smith

By Baseline Staff Apr 26, 2024Open Up: A Player Portrait

Grigor Dimitrov’s open heart is a driving force behind his career renaissance

By Matt Fitzgerald Apr 26, 2024Travel

Destination Tennis: Owl’s Nest Resort

By Megan Fernandez Apr 26, 2024Pick of the Day

Jaume Munar vs. Jan-Lennard Struff, Mutua Madrid Open

By Zachary Cohen Apr 26, 2024Madrid, Spain

Joao Fonseca wins Masters 1000 debut in Madrid over fellow teen Alex Michelsen

By TENNIS.com Apr 25, 2024In Memoriam: Pancho Segura, Vic Braden, Dennis Van der Meer

The Three Wise Men elevated the way tennis is played at every level, everywhere they went. Remembering three iconic instructors who recently left us, but whose impacts upon the sport endure.

Published Dec 13, 2019

Advertising

The gravitational motion of tennis pulls towards solitude. Loneliness. Isolation. Distance. These are the attributes that accompany the journey taken by our sport’s driven competitors. When studies explain why people leave tennis, a frequent reason is downright melancholy: I couldn’t find anyone to play with me.

Dennis Van der Meer (1933-2019), Vic Braden (1929-2014) and Pancho Segura (1921-2017) counterattacked solitude with glee, insight and generosity. If you didn’t laugh or learn something within 15 minutes of meeting any one of these instructors, you had no sense of humor, and zero likelihood of becoming a tennis player.

When a facility seeks a new tennis director who can whip up enthusiasm, the Van der Meer legacy is vivid. When a student laughs while attempting to improve a stroke, hark back to Braden. When a player recognizes how best to play the 15–30 point, and how that differs from 40–15, tip the hat to Segura. The tennis boom of the 1970s propelled each instructor into the limelight, and their impacts are still being felt today.

Namibia, Africa; Monroe, Michigan; Guayaquil, Ecuador. The places where Van der Meer, Braden and Segura respectively grew up were light years removed from anything notable in tennis. Van der Meer, the child of missionaries, was shown the game by his mother with a rope and a stick. Braden, caught stealing tennis balls at a local facility, was told by the man who apprehended him that he could either go to jail or learn tennis. Segura’s father was the caretaker of a local tennis club. For each, life was tennis or bust.

When Van der Meer learned that he wasn’t quite good enough to make the South African Davis Cup team, he decided to dedicate himself to instruction. Braden was ranked as high as No. 25 in the U.S. in the 18s, but soon came to love teaching. Segura went to the top as a player, but he would leave his greatest mark as a coach.

The three came in proximity upon Van der Meer’s arrival in the U.S. in 1961, when he became head pro at the Berkeley Tennis Club (BTC) in the San Francisco Bay Area. One of the sport’s preeminent clubs, it was the tennis home for such stars as Helen Wills and Don Budge. That same year, Braden convinced Jack Kramer (whom he aided as part of his barnstorming pro tour) to open a new facility in Rolling Hills, a Los Angeles suburb. When the Jack Kramer Club opened, its first court was named for Segura.

In Memoriam: Pancho Segura, Vic Braden, Dennis Van der Meer

© Sports Illustrated via Getty Images

Advertising

By the 1950s, Segura was one of the best players in the world, but it was his wildly successful coaching tenure with Jimmy Connors that would define his legacy. (Getty Images)

Though still playing great tennis at 41, Segura at last left the tour in 1962. His new pursuit would be as head pro at the Beverly Hills Tennis Club (BHTC), its pedigree marked by the Hollywood folk who’d started the club in large part because, as Jews, they’d been barred from joining the prestigious Los Angeles Tennis Club. The BHTC also boasted a number of players who competed at the highest level.

So it was that by 1963, these three were based at facilities that were prominent launching pads for tennis excellence. But each man was also about to take a new approach to interacting with students. Instruction had long been a top-down experience: the teacher knew more. With the manner of a dictator, the teacher imposed that information. Grasp it and you ascended to the status of being a bona fide player. If not, consider yourself a hacker. There were even instructors who would tell members to take their meager skills and only play on the club’s backcourts. Such was the small tennis community in the days of exclusionary membership policies, the Great Depression and World War II. Said a man who’d joined the BTC in the 1930s, “It was a tiny sport that no one paid attention to.”

Post-war affluence altered the picture. Parents wanted good things for themselves and their children: piano, swimming, tennis. Far more people could afford club memberships. These new members of the affluent class weren’t just compliant students, content to occupy the castle. They were customers, expecting they would be catered to. Deeply aspirational, each scarcely born to the tennis manner, Van der Meer, Braden and Segura were so eager to connect that they also possessed this special quality: the ability to make tennis entertaining and enjoyable. To tear down the wall.

In Berkeley, Van der Meer ceaselessly walked the land. From juniors to adults, beginners to the nationally ranked, backboards to ball machines, no aspect of the game escaped him.

“He was very practical about technique,” said Lynne Rolley, a junior member of the BTC in the 1960s, who later became head of women’s tennis for the USTA. “He would teach his students how to make contact with the ball in all sorts of useful and engaging ways.” (Van der Meer also enjoyed the company of his pet cheetah, “Drop Shot,” who he would bring to the club and let rest in the back of his teaching court.)

Braden’s Kramer Club juniors rapidly became quite successful, earning dozens of trophies. But none were more notable than the five children of a pro shop employee named Jeanne Austin. Four of Jeanne’s progeny, most notably Tracy, became pros.

“He was the man, like Wolfman Jack, cooking up all the great tunes,” said Wayne Bryan, father to Mike and Bob, who lived near the Kramer Club.

Braden would also take pride in showing how young Tracy’s swing shape at the age of 6 was similar to the one that earned her two US Open titles. Here also was where Braden first honed such sayings as, “you’ll be famous by Friday” and “air the armpit”— the latter a pointer for hitting a topspin backhand. So engaging were Braden’s lessons that they would draw audiences. Said Tracy, “Vic made it fun.”

Segura’s world was a who’s who of 1960s Hollywood, his students including Charlton Heston, Doris Day, Burt Bacharach and many others who came as much for his quips as his pointers.

“Buddy,” Segura would say with a twinkle, “Why don’t you take two weeks off and then quit?” The student would laugh and show up for more.

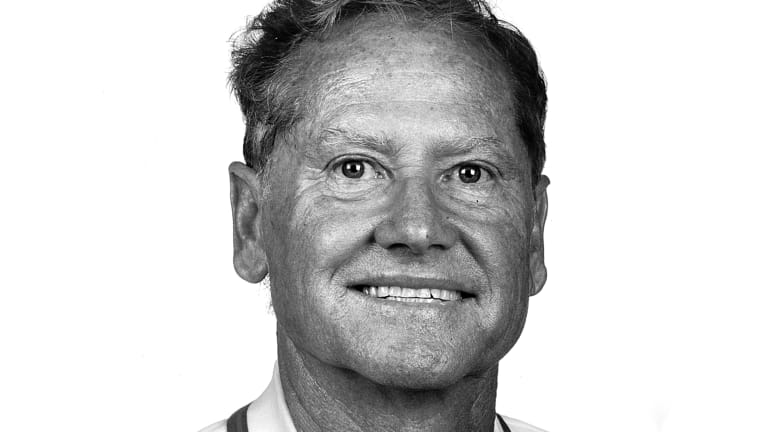

In Memoriam: Pancho Segura, Vic Braden, Dennis Van der Meer

Advertising

Van der Meer didn’t learn the game in luxury, but his modest upbringing “gave him the ability to rally forever with one ball.” (Getty Images)

There were also elite players. In his early years at the BHTC, Segura aided the development of future Hall of Famers Stan Smith, Arthur Ashe and Charlie Pasarell. His forte was match strategy, and a cocktail napkin was his chalkboard: Segura diagrammed a mind-blowing trip around the court— power, angles, touch, height, depth, speed and spin. The court became the classroom, where Segura would concurrently play and instruct.

Never was this more vivid than on a summer day in 1968, when 30 minutes after hitting with a bandy-legged 15-year-old from Illinois, Segura told his son Spencer that he had just hit with a future No. 1. Jimmy Connors soon moved to California.

Open tennis, beginning in 1968, was the tipping point that triggered the tennis boom, and each of these three minds was primed for stardom. Van der Meer took the tennis camp to new levels—“Nobody was better at truly reaching people,” said Professional Tennis Registry CEO Dan Santorum.

Van der Meer’s visibility was also helped that, while at Berkeley, he’d met world No. 1 Billie Jean King, who he would coach for the 1973 “Battle of the Sexes” match with Bobby Riggs. (Van der Meer had also coached Margaret Court when she played Riggs.) By the early ’70s, Van der Meer had relocated to Hilton Head, where he built one of the world’s most successful tennis communities. In the ’80s, his wife Pat also stepped into a major role.

Braden left the Kramer Club in 1971 to open the Vic Braden Tennis College. Like Van der Meer, Braden transformed the weekend getaway, instructed teachers and became a renowned expert, an author of articles (including those for TENNIS Magazine) and landmark books. Joined by his wife, Melody, an accomplished photographer, Vic travelled the world, persistently gathering images, learning and teaching.

Segura also relocated, to the San Diego area, for a venue that became a playpen for the rich and famous: La Costa Resort & Spa. From 1970 to ’95, he continued to teach and also devote time to Connors and other ambitious players such as the young Michael Chang. Segura had left his fingerprints on a pantheon of American champions who excelled across four decades.

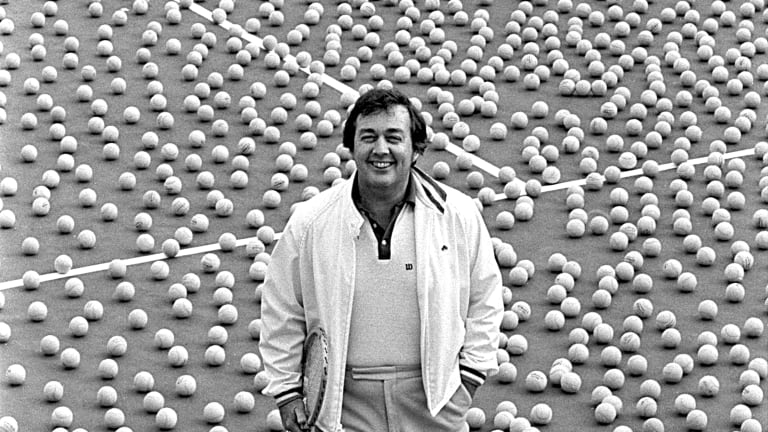

In Memoriam: Pancho Segura, Vic Braden, Dennis Van der Meer

© © John G. Zimmerman Archive

Advertising

Stroke mechanics were a point of pride for Braden, but even more importantly, he wanted to make sure playing tennis was fun for everyone. (Getty Images)

Over the course of nearly 40 years, I was lucky enough to interact with each of these three men, and experience their spirit of inclusion and years of wisdom first-hand. Segura and I spent many hours and days together, on the court and off, his wisecracks vying neck-and-neck with his analysis. Never will I forget the day at the 2000 US Open when we watched two players and Segura issued a prediction: “This guy is pretty steady and will probably win a French Open or two.” He was spot on about Juan Carlos Ferrero, who would win that match and earn his lone Slam at Roland Garros in 2003.

“But this other guy,” Segura added, “he’s incredible, like [Ilie] Nastase. If he can get it together, he’ll have a career like Pete Sampras.” Roger Federer was 19 years old that afternoon.

Since 1990, I have been a member of the Berkeley Tennis Club. When I told Van der Meer I played there, he rattled off the details of many members, their strokes and those sunny California afternoons when he’d first built his career.

Braden was always an accessible, intelligent and kind source—never more so than when he devoted hours to our collaboration on a 1998 cover story on brain typing, a controversial but compelling way to understand the distinct ways people take in information and, as he saw it, can best learn how to play tennis. We also connected on an emotional level, having each lost loved ones to the same disease, lupus.

These three men had touched so many people, and were always aware of how special it was to have come from nowhere to build a life in a passion. The title of Braden’s last book personified each man’s sensibility: If I’m Only 22, How Come I’m 82?

It was a chilly December morning and I was playing doubles with Segura. He was past 80 then, still eager to passionately compete and instruct in what, afterwards, I called a meaningless match. Countered Segura: “Buddy, when I walk on a tennis court, it always matters