The Rally: When the real world has pushed tennis to the sidelines

Mar 14, 2020San Diego Open

ATP cancels China swing, including Shanghai Masters, and adds six 250 events to 2022 calendar

card-sponsor-pre TENNIS.com Jul 21, 2022Australian Open

Pandemic surge hits Australian Open: Bernard Tomic's COVID-19 prediction comes true, spectators capped at 50 percent

card-sponsor-pre Kamakshi Tandon Jan 13, 2022Australian Open

Novak Djokovic has been exempted—but his stance hasn’t been vindicated

card-sponsor-pre Steve Tignor Jan 04, 2022Australian Open

Rafael Nadal back on track for Australian Open following COVID-19 case

card-sponsor-pre Kamakshi Tandon Dec 30, 2021Australian Open

Aussie Open field starts to experience effects of pandemic surge, vaccination issues

card-sponsor-pre Kamakshi Tandon Dec 21, 2021"It will happen this year": Stefanos Tsitsipas planning to get COVID-19 vaccine

card-sponsor-pre Kamakshi Tandon Sep 21, 2021US Open

Going to the US Open? Proof of vaccination status now required after change in COVID-19 policies

card-sponsor-pre TENNIS.com Aug 27, 2021US Open

A vaccinated Sofia Kenin to miss 2021 US Open due to positive COVID-19 test

card-sponsor-pre Matt Fitzgerald Aug 26, 2021Australian Open

The Rally: if you wanna play a major, you must play by the local rules

Jan 18, 2021The Rally: When the real world has pushed tennis to the sidelines

In the first of a new series of discussions about our sport, Steve Tignor and Joel Drucker talk about the (few) other moments in history that have taken the tennis court out of play.

published_tag Mar 14, 2020

Advertising

The Rally is a new series of discussions about tennis in which Joel Drucker and Steve Tignor will step back and look at the bigger picture surrounding the sport. In the inaugural edition, they talk about the (few) other moments in history when the real world has pushed tennis to the sidelines.

Joel,

We’ve come a long way in just six days. A week ago, we were gearing up for Indian Wells; now we’re looking at a month and a half, or longer, without tennis. For me, it’s the daily-ness of the sport I miss. For 11 months, it’s always there, always a channel change away. Because tennis is global and dual-gender, it feels like an alternative world, at least to me, in a way that other all-male, U.S.-based sports don’t.

I’ve been following that world since the mid-1970s, and I can’t remember a time when it just…vanished. If 9/11 had taken place a week earlier, it surely would have shut down the US Open in 2001; as it was, Venus and Serena Williams played the first prime-time women's final that Saturday, three days before the Twin Towers fell.

But tennis hasn’t always remained unscathed. I can’t find any evidence that tournaments were cancelled due to the influenza pandemic from 1918 to 1920, but that may have been because they had already been shut down for World War I. Years later, when Jack Kramer described his first trip to Wimbledon in the 1940s, he talked about how Centre Court had a giant hole, made by five 500-pound German bombs that were dropped on it during World War II. It took nearly 10 years to repair.

As we while away our time with no tennis, Joel, are there any other world events you know about that had a comparable impact on the game?

The New Normal: Tennis world on hold

Advertising

Steve,

What’s happening now is completely unprecedented. I live in Northern California and last weekend I flew to see my family in L.A. before driving east to Indian Wells. So on Sunday night, to get word of it being cancelled, was just staggering.

Again, though there’s nothing to rival the current situation, there have been a few moments when the world collided with tennis. That there have only been a few shows how fortunate we’ve been.

The 1968 French Open took place amid the massive civil disorder that tore Paris apart that spring. Amid street riots, demonstrations, public protests, a garbage strike, sporadic telephone service and the persistent smell of tear gas, the tournament’s organizers considered cancelling the entire event. With the airport in disarray, there were tales of players paying hundreds of dollars to take cabs from places like Brussels and Luxembourg. Another player told me she had to change hotels three times. Oddly enough, with so much of Paris off-limits, the tennis thrived, attendance tripling over the previous year.

Yesterday, pondering this topic of disrupted tennis tournaments, I called Dick Stockton. In 1976, Stockton was one of four semifinalists competing at a WCT event in Lagos, Nigeria. Weeks prior, reading various news reports, Stockton told WCT tour leaders he was concerned there might be a coup.

Sure enough, that’s what happened. The country’s president was assassinated mid-tournament and the military sought to impose order. Though Stockton completed his semifinal, the next one, between Arthur Ashe and Jeff Borowiak, was literally interrupted at gunpoint when a group of soldiers entered the court and shoved a gun into Ashe’s back. There followed a hectic evacuation and several anxious days of time spent shuttling back and forth between a hotel, a diplomat’s residence and a scary interaction past curfew at a military roadblock that included machine guns pointing into the car. Six weeks later, in Caracas, Venezuela, Stockton, Ashe and Borowiak finished the tournament.

But again, both Paris and Lagos were transitory and also confined to one spot. As more cancellations occur, Steve, how do you think that will alter the way tennis aficionados engage with the sport?

Jon Wertheim on how much has changed since the Indian Wells postponement:

Advertising

Joel,

Wow, I’m not sure I had ever heard the Lagos story, at least the part about Ashe having a gun stuck in his back while he was on the court! When are we going to see a feature-length movie made of his life? I could see Lagos as the opening scene.

First, though, I guess we have to get to a point where we actually feel safe going to movie theaters again. Obviously I don’t know what it’s like to be on a war-time footing—the food rationing, curfews, blackouts, and nationalized industries that we’ve seen portrayed in so many books and movies. But I’m starting to get a slight sense of what that constant, anxious, pent-up feeling must have been like during the World Wars. Everything you thought was important and permanent suddenly just stops.

Tennis was one of the things that stopped, at least outside the United States, during WWI and WWII. Davis Cup, Wimbledon and the Australian Open were suspended during both wars. The US Nationals (now called the US Open), though, has never been cancelled; it was far from the action in New York, and the sport was less globally integrated in the days before commercial air travel.

That said, the latter rounds of the Davis Cup were being held in the United States when World War I broke out in 1914, and the interaction of the two events could have come straight from a film script. Australia, led by two all-time greats, Norman Brookes and Anthony Wilding, was scheduled to play Germany in Pittsburgh at the end of that July. Two days before the tie, Austria declared war on Serbia. Here’s how one of our favorite tennis historians, Digby Baltzell, described what happened on the third day of the tie in Pittsburgh, when it was clear that Germany was about to join the war.

“The club president feared interruption, and telephone lines were cut off and newspapermen excluded from the club. Sometime during the afternoon, while both Wilding and Brookes were winning their matches, news reached the club that Germany had declared war on Imperial Russia. As the last ball was played, a megaphone announced the sad news to the silent crowd. The German team hurried to board a ship for home.”

As for the Australians, they went on to the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, where they won a classic tie, 3-2, over the U.S. in the Davis Cup Challenge Round. Brookes (the Australian Open men’s champion’s trophy is named after him) went to Egypt and served in the red cross during the war. Wilding, who looked like the tennis player of every Hollywood producer’s dreams, would meet a crueler fate: He was killed in a trench in France. According to Baltzell, he was talking about the Davis Cup final with a fellow soldier the night before he died.

Advertising

The Rally: When the real world has pushed tennis to the sidelines

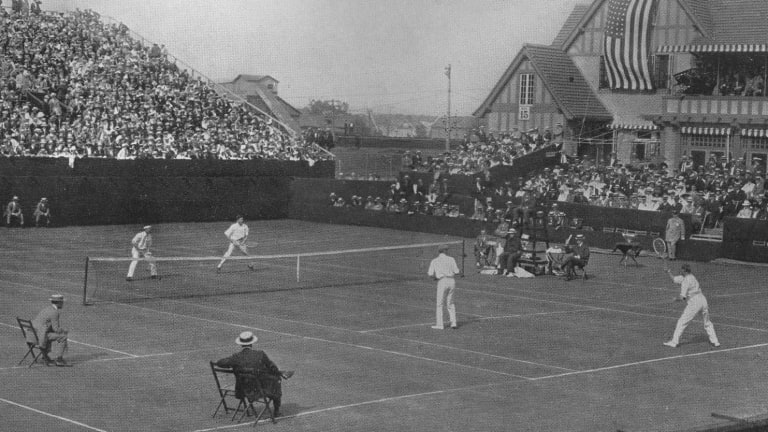

The 1914 International Lawn Tennis Challenge (Davis Cup) finals match between Australasia and the United States played at the West Side Tennis Club in New York City, New York on 13–15 August. Players shown on the near side are Norman Brookes (left) and Anthony Wilding (right) for Australasia and on the far side Tom Bundy (left) and Maurice McLoughlin (right) for the United States. (Wikimedia Commons)

That was essentially it for tennis for four years. But the sport eventually came back, and with a bang, after the war. In 1919, Suzanne Lenglen won her first major title; the following year, Bill Tilden did the same. Those two all-time greats make tennis a major part of the Golden Era of Sports in the 1920s.

Considering that we’ve been going through our own golden age, let’s hope the coronavirus doesn’t spell the end of the Federer, Djokovic, Nadal, Serena era. I don’t know about you, Joel, but I’d be more than happy to have a lengthy GOAT debate, rather than keep talking about what we’re talking about these days.

Mark Knowles on how the ATP is handling player concerns:

Advertising

Steve,

You were so right when citing things like wartime footing and all that pent-up energy, anxiety and uncertainty—and also, in this case, the awareness that there are a lot more important things than tennis.

It rained heavily in Los Angeles on Thursday—grey skies, dark, gloomy, with more rain anticipated in the days to come. Watching pro tennis? Off the table. But also here in one of the world’s most tennis-crazy regions, the chance to have respite from all this stress and even play tennis vanished too. Again, hardly a major problem.

The implications of this incredible worldwide crisis on a global sport like tennis are profound. Players, officials, agents, media et al are constantly on planes, departing and arriving in different cities and countries—and always greeting one another at each stop with soulful handshakes and hugs. What’s to come of this racquet-toting United Nations, not just in the coming weeks, but over the course of 2020 and beyond? Does the circuit eventually become hyper-regionalized? I remember going through stringent security screening at tournaments after 9/11. What’s to come now?

I spent much of Thursday talking to Southern California-based tennis folk for a story about this area’s reaction to all that’s happenings. While of course all are concerned, there was also recognition that the planet has faced other crises and gotten through them. L.A. resident Vijay Amritraj, the former Indian great who at one time was the president of ATP Player Council and has also been a UN Messenger of Peace, told me about the time he was playing in Kuwait in the early ’80s when a war between Iran and Iraq broke out—some of the fighting taking place just across the water from where he was competing. And his match continued. Anne White, an ex-WTA pro who’s the director of tennis at the Beverly Hills Tennis Club, recalled being in Geneva when SARS broke out.

Indeed, tennis folk have had their share of experiences when the world took a tumble and they were far from the comforts of home. This situation, of course, is quite different.