Competing as a graduate student-athlete is an option worth pursuing

By Apr 08, 2020San Diego Open

ATP cancels China swing, including Shanghai Masters, and adds six 250 events to 2022 calendar

By Jul 21, 2022Australian Open

Pandemic surge hits Australian Open: Bernard Tomic's COVID-19 prediction comes true, spectators capped at 50 percent

By Jan 13, 2022Australian Open

Novak Djokovic has been exempted—but his stance hasn’t been vindicated

By Jan 04, 2022Australian Open

Rafael Nadal back on track for Australian Open following COVID-19 case

By Dec 30, 2021Australian Open

Aussie Open field starts to experience effects of pandemic surge, vaccination issues

By Dec 21, 2021"It will happen this year": Stefanos Tsitsipas planning to get COVID-19 vaccine

By Sep 21, 2021US Open

Going to the US Open? Proof of vaccination status now required after change in COVID-19 policies

By Aug 27, 2021US Open

A vaccinated Sofia Kenin to miss 2021 US Open due to positive COVID-19 test

By Aug 26, 2021Australian Open

The Rally: if you wanna play a major, you must play by the local rules

Jan 18, 2021Competing as a graduate student-athlete is an option worth pursuing

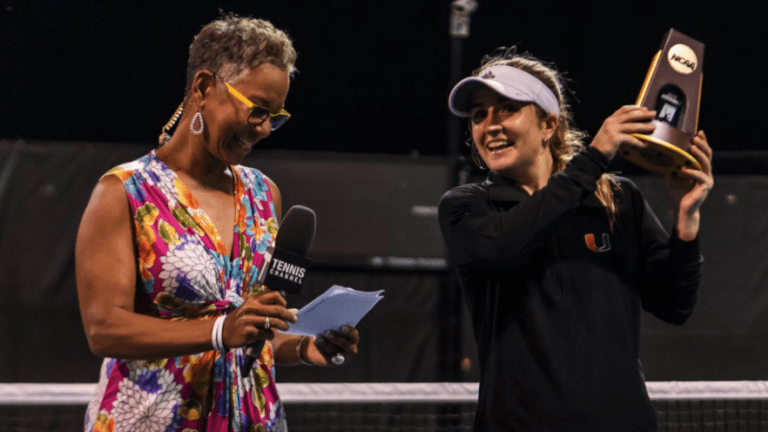

With the NCAA returning a season of eligibility to spring student-athletes, players should consider extending both their educations and competitions in the college space.

Published Apr 08, 2020

Advertising

Competing as a graduate student-athlete is an option worth pursuing

Advertising

Competing as a graduate student-athlete is an option worth pursuing

Advertising

Competing as a graduate student-athlete is an option worth pursuing

© Getty Images

Advertising

Competing as a graduate student-athlete is an option worth pursuing

Advertising

Competing as a graduate student-athlete is an option worth pursuing