The iconic Los Angeles Tennis Club hits the century mark

By Joel Drucker Dec 23, 2020Olympic organizers unveil strategy for using artificial intelligence in sports

By Associated Press Apr 19, 2024Football star Reggie Bush is now a tennis dad

By Ed McGrogan Apr 19, 2024ATP Barcelona, Spain

Stefanos Tsitsipas climbs Barcelona "mountain" after saving match points to edge Diaz Acosta

By TENNIS.com Apr 19, 2024Ruud and Tsitsipas advance to Barcelona semifinals, one step away from another title clash

By Associated Press Apr 19, 2024Swiatek beats Raducanu in Stuttgart quarters. Sabalenka loses to Vondrousova

By Associated Press Apr 19, 2024Style Points

Zendaya pays tribute to the Williams sisters in Carolina Herrera gown and white beads

By Baseline Staff Apr 19, 2024WTA Stuttgart, Germany

Iga Swiatek defeats Emma Raducanu, extends Stuttgart win streak into semifinals

By David Kane Apr 19, 2024Tennis umpire banned for life for manipulating scores and gambling

By Associated Press Apr 19, 2024ATP Munich, Germany

Cristian Garin repeats history by ousting Alexander Zverev in Munich quarterfinals

By TENNIS.com Apr 19, 2024The iconic Los Angeles Tennis Club hits the century mark

To walk around the LATC and to talk with members, to take in the way the grounds combine vintage and contemporary, reveals a vivid possibility: the potential for history not to merely occupy shelf space, but to repeatedly echo.

Published Dec 23, 2020

Advertising

On a December day 12 months ago, the Los Angeles Tennis Club (LATC) buzzed and hummed with talk and tennis. Begin with the magical glow that accompanies playing outdoors underneath a glittering winter sky, while most of the rest of the country is shoveling snow. This weather advantage—especially during the many decades when indoor facilities were scant—greatly helped all of California get a competitive jump on the entire world. But for a good half-century, from 1920 to 1970, no single tennis facility gained more from that edge than the LATC.

At the LATC last December, several adults contemplated their next league season. Yelling from one court to another, a longstanding member made wisecracks about his friend’s old-school forehand. A Hollywood agent was taking a lesson on Court 13. A guest noted how the 14 hard courts were once painted black but now bore a crisp, contemporary azure. On one of the club’s two Har-Tru courts, an accomplished age group player began a drilling session with his personal coach. There was the cozy snack bar, where Arthur Ashe collected $80 in bets the night Billie Jean King beat Bobby Riggs back in 1973. “Latke Night,” a Jewish-theme holiday celebration, was happening in a couple of days. Come Friday evening, under the eyes of head pro Jerome Peri, five courts would be devoted to “Live Ball” workouts. In the men’s locker room, a funny tale was told about Hall of Famer Gene Mako, a persistently animated member who’d been part of LATC from the 1930s until his death in 2013 at the age of 97.

And then there was the promise of 2020, the year the club would turn 100 and celebrate its place as one of the most fabled venues in tennis history. Events were in the works, lively materials drafted, iconic photos framed, intriguing trophies dusted.

The pandemic put much of that activity on hold, save for a club-wide Zoom toast held on October 27, 100 years to the day since the club’s founding. Still, to walk around the LATC and to talk with members, to take in the way the grounds combine vintage and contemporary, reveals a vivid possibility: the potential for history not to merely occupy shelf space, but to repeatedly echo.

The iconic Los Angeles Tennis Club hits the century mark

Advertising

Located in the upscale neighborhood of Hancock Park, the Los Angeles Tennis Club was founded in 1920. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Tennis Club)

The iconic Los Angeles Tennis Club hits the century mark

Advertising

The Los Angeles Tennis Club as it stands today—16 courts, 14 hard, two Har-Tru. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Tennis Club)

Once upon a time, American tennis was strongly feudalistic. Across various cities, grand tennis castles served as epicenters of the sport’s competitive culture. These included Boston’s Longwood Cricket Club, which hosted the U.S. Doubles championship from the 1930s until 1967, and New York’s West Side Tennis Club, in Forest Hills, home of the U.S. Nationals (later US Open) until the end of 1977.

Located in Hancock Park, an upscale neighborhood seven miles west of downtown Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Tennis Club opened in 1920. Its first president was Thomas Bundy, a three-time winner of the U.S. doubles championship. Bundy’s wife, May Sutton, had been the first American to win Wimbledon when she’d taken the singles in 1905. Their daughter Dorothy, later known to the world as “Dodo” Cheney, went on to win the singles at the 1938 Australian Championships, earn a record 394 USTA national age group titles, and join her parents in the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 2004.

Such prominent lineage commenced the greatest royal procession from a single club the sport has ever seen. By the 1930s, a steady stream of future Hall of Famers made the LATC their base of operations, Wimbledon and U.S. singles champions Ellsworth Vines, Bobby Riggs, Jack Kramer and Ted Schroeder among the notables surfacing in that decade. Bill Tilden, world No. 1 for most of the 1920s, relocated to Los Angeles and played frequently at the LATC, as did Don Budge in the 1940s. Soon after came Pancho Gonzales.

The nation’s premier college team, the University of Southern California, practiced and played at the LATC, in the 1950s and 1960s spawning four more Hall of Famers: Alex Olmedo, Rafael Osuna, Dennis Ralston and Stan Smith.

The LATC also hosted the Pacific Southwest Championships, an event often considered the second-most important tournament in the country. Kramer once told me that it was harder to win the “Southwest” than Wimbledon.

For most of the 20th century, if you were any kind of ambitious player, you needed to come to terms with the LATC, largely by competing at its many prestigious events and also vying with its deep roster of skilled players.

“The East Coast had all those clubs,” said Kramer, “but we had all the players.”

The head honcho was a prim and proper man named Perry T. Jones. From 1923 to 1970, the LATC as his base, Jones ruled Southern California tennis, heavily focused on shaping the fate of the section’s best players. Much as Harry Hopman had done with the Australians, Jones imposed a strict code of conduct, a strong belief in sportsmanship, manners, hard work and grooming. Disobey and you would have no chance of being allowed to play significant tournaments.

LATC being a castle, there was a profound hierarchy. This was a world defined largely by lords—majordomo Jones and his dominion of great players—and serfs: the mass base of LATC members, content to reside in the kingdom. So it went for the club’s first 50 years.

The iconic Los Angeles Tennis Club hits the century mark

Advertising

Aerial view of the Los Angeles Tennis Club, taken in 1937. (UCLA Department of Geography, Benjamin and Gladys Thomas Photo Archives, Fairchild Aerial Surveys Collection)

How does such a rich history jibe with the last half-century of life at the Los Angeles Tennis Club? Grasping the past hardly matters at the vast majority of tennis clubs. They primarily exist as recreational facilities, largely present in the here and now. For a former castle, though, memory yields opportunity and challenge.

The coming of Open tennis—naturally, in the tumultuous year of 1968—commenced a sea change in how the sport operated and in many ways completely transformed the LATC. The “Southwest,” always an amateur event, had compensated players under-the-table in what was known as “shamateurism.” But once money entered tennis in a legitimate way and the sport’s popularity soared, it became rapidly clear that quaint clubs lacked the infrastructure to host pro tennis tournaments—and that the leverage amateur officials like Jones had over players was about to vanish in the face of the marketplace.

In an even more profound way, the club’s transition from Old World to New World was marked by Jones’ death in September 1970. His iron hand nurtured excellence, but also came with a price tag, a penchant more towards exclusivity than inclusion. “Latke Night” at the LATC in Jones’ era? Not likely. Five years after Jones died, Ashe asked the club to integrate and offer membership to Otis Smith III, a promising young black player (it did).

The iconic Los Angeles Tennis Club hits the century mark

Advertising

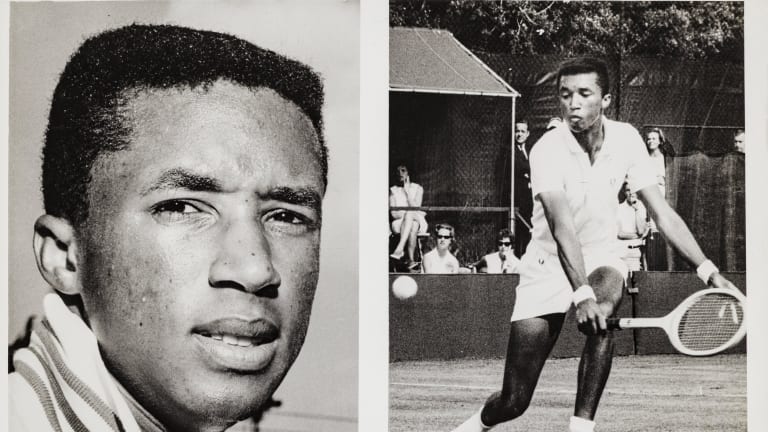

While still an undergraduate at UCLA, Arthur Ashe won the 1963 Pacific Southwest Championships, held at the Los Angeles Tennis Club. Twelve years later, he successfully advocated for the club to integrate and offer membership to Otis Smith III, a promising young black player. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Tennis Club)

Another small but eventually catalytic incident occurred in the summer of 1955, when Jones told an 11-year-old girl competing at a junior tournament held at the LATC that she could not be part of a group picture because she was wearing shorts instead of a dress. In her autobiography, the girl who that happened to wrote that, “I think I sensed without ever really being able to say it that if I ever got the chance I was going to change tennis, if I could, and try to get it away from that kind of nonsense.”

Meet young Billie Jean King, politicized at the LATC.

Fifteen years later, angry that the “Southwest” was offering women eight times less prize money than the men, King and eight other players joined forces with World Tennis publisher Gladys Heldman to boycott the “Southwest” and instead start their own circuit, competing in Houston at a new event, the Virginia Slims Invitational.

After 1974, the “Southwest” left the LATC for a larger venue on the UCLA campus (though it briefly returned from 1981-’83), depriving the club of a key source of revenue and prestige. Also in the 1970s, USC opened its own on-campus facility.

No longer the center of big-time tennis, the LATC spent a couple of decades in readjustment mode. As has happened at many of America’s tennis castles, amid uncertainty about what steps to take to remain vibrant, facilities eroded, managers came and went, membership fluctuated.

But in the last 20 years, the club rebounded sharply. Significant money was spent to rebuild the area alongside the club’s stadium court, including the creation of new locker rooms, a redesigned bar and dining area. To witness the LATC now is to see a sparkling facility, from the courts to the pool, gym and dining area, to the team of eight instructors, to a wide range of events catering to all levels of recreational activity. “We are very much of club for families,” says LATC general manager Layosh Toth.

Even more notable in the post-Jones era there came a shift in membership policies, the club now increasingly diverse and seeking ways to make an impact as a citizen—be it with philanthropy, outreach, events and youngsters throughout Los Angeles. For 20 years, the LATC has annually staged “Tennis for Tots,” a charity event that has raised more than $2 million to benefit foster children. Recently, the club has started to form a diversity and inclusion committee.

The iconic Los Angeles Tennis Club hits the century mark

Advertising

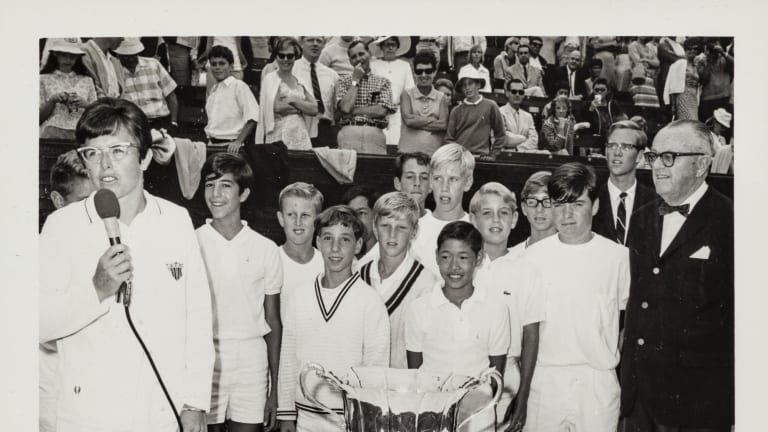

Competing at the Los Angeles Tennis Club greatly propelled Billie Jean King’s ambitions—both inside and outside the lines. On the far right is SoCal tennis czar Perry T. Jones, the man who inadvertently helped politicize King when she was 11 years old. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Tennis Club)

And history? How does that play out these days? Many a member of a legacy club scarcely cares to know about prior greats. After all, what does the tennis journey of Jack Kramer have to do with someone keen on his next league match?

But maybe it can make a significant difference. Excellence can inspire, a catalyst for players of all ages and stages to study, improve and enjoy the game. Fancy the aspiring player who hits on the court where Kramer and Schroeder worked with Cliff Roche, a retired engineer, to study the geometric nuances of serve-volley tennis. Or take a walk to Court 5 at the LATC, where in 1970, 18-year-old Jimmy Connors beat the legendary Australian, Roy Emerson, to earn what Connors has always considered his first big win. Or the young Billie Jean, peeking through the fence when competing there to overhear the advice Gonzales was giving to Ralston. Or Jones, explaining the significance of sportsmanship to aspiring juniors.

In December 2017, the International Tennis Hall of Fame staged a ring ceremony for Olmedo that also featured Hall of Famers who had extensive experiences at the LATC—Stan Smith, Charlie Pasarell, Tracy Austin, Rod Laver. In large part, this event helped even LATC members discover their own club and see it in a fresh, new light.

Now having turned 100, the LATC is joining the Association of Centenary Clubs, a worldwide organization of many (but not all) clubs, including nine in the United States. A modest proposal: All of these clubs open their doors to visitors, to let anyone who loves tennis examine its lively history and, perhaps even more importantly, take in such enduring values as sportsmanship, grace, mutual respect for opponents and the game. What were once castles could well continue as dynamic cathedrals.