The 2/21: The literature of Arthur Ashe, 28 years after he left us

By Feb 06, 2021Betting Central

Line Calls, presented by FanDuel Sportsbook: ATP Mutua Madrid Open Betting Preview

By Apr 24, 2024Madrid, Spain

Despite jet lag, Sloane Stephens keeps winning in Madrid with big goals for clay swing

By Apr 24, 2024Social

It's a girl! Belinda Bencic welcomes her first child, a daughter named Bella

By Apr 24, 2024Madrid, Spain

Naomi Osaka victorious in Madrid return, defeats Greet Minnen for first clay win since 2022

By Apr 24, 2024Brian Tobin, former president of the International Tennis Federation, dies at age 93

By Apr 24, 2024Madrid, Spain

Elena Rybakina is a sore winner (this is a good thing)

By Apr 23, 2024Zendaya, Josh O'Connor and Mike Faist on the steamy love triangle of 'Challengers'

By Apr 23, 2024Madrid, Spain

Tatjana Maria will follow daughter Charlotte’s first tournament on live scores from Madrid

By Apr 23, 2024Madrid, Spain

“I hope to make it”: Carlos Alcaraz eyes Madrid three-peat for 21st birthday gift

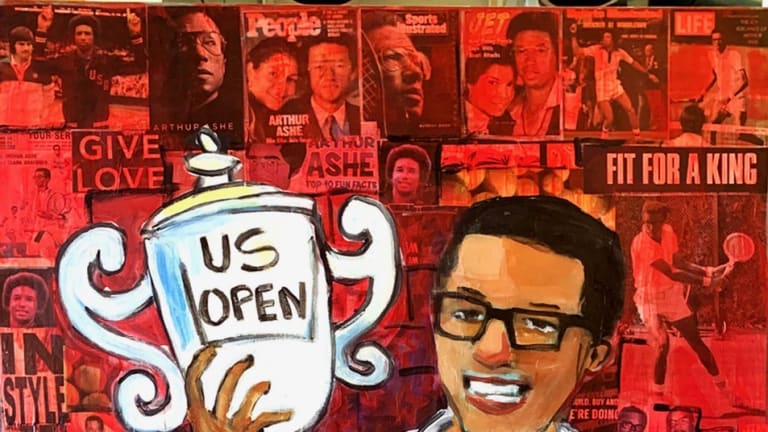

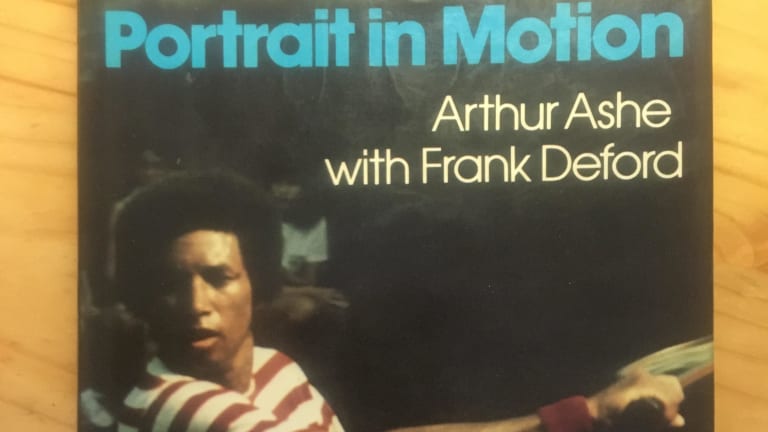

By Apr 23, 2024The 2/21: The literature of Arthur Ashe, 28 years after he left us

No other tennis player spanned as many historic moments and iconic venues; as such, the narrative possibilities become epic.

Published Feb 06, 2021

Advertising

The 2/21: The literature of Arthur Ashe, 28 years after he left us

Advertising

The 2/21: The literature of Arthur Ashe, 28 years after he left us

Advertising

Advertising

The 2/21: The literature of Arthur Ashe, 28 years after he left us

Advertising

The 2/21: The literature of Arthur Ashe, 28 years after he left us