If you live in New York, the first sign of the holiday season is not the sight of a titanic, glittering tree or a robot Santa swiveling his hips in front of a department store. It’s something both more mundane and harder to escape: One day in early December you walk out of your apartment and realize that you’re surrounded by even more people; this hardly seems possible in a city that already holds 9 million. Not only that, many of these people are smiling, and many are wearing colors other than black, the mandatory color of Gotham. This also seems hard to believe, but there they are, couples and families and brace-faced teenagers gazing wide-eyed, happy to find themselves in Rockefeller Center, happy to be jostled through Times Square, happy to eat at Sardi’s, happy, even, to ride the subway.

I can understand the appeal; I’ve been there. My sister and my parents and I visited New York from Pennsylvania during the Christmas season a few times when I was a kid. There’s a nice picture of us jammed together, smiling, in front of that titanic, glittering tree in Rockefeller Center. Even now, as a full-time, longtime New Yorker, I enjoy the bright, bustling spirit that descends on the concrete jungle during the holiday season. In the evenings, walls and bushes and lampposts that are normally dark and nondescript are outlined in sparkling red and green and white. Around the boroughs, chatty gangs of people pack themselves five deep at bars and escape the cold by hustling for the dim warmth and soothing noise of a restaurant. This past Tuesday, at a dim, warm, noisy, brasserie-style restaurant in Brooklyn, I had to hang my winter coat on top of five others on a tiny peg behind my chair. At any other time of year, I would grumble to myself about the masses of humanity in New York, about what a hassle it can be here just to get a seat at a restaurant on a Tuesday night. Why, three days before Christmas, did it feel so comforting to be caught up in that same humanity?

Why? Answering that would require figuring out what the meaning of Christmas is to us relatively godless, relatively liberal types in this country. I’m probably not the best person to ask; I’ve still never fully understood the idea that “Jesus died for our sins,” except that it helped give us a great Patti Smith line: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine.” (Not that I really understand that line, either.) The Christmas most us know now is about communing with friends and family, remembering the people we love. It’s the time of year when we collectively decide, for one month, that life is pretty good—bright, sparkling, colorful, festive—after all.

What if you can’t buy into that message, if you can’t find that spirit, if your life doesn’t happen to be perfect when December rolls around? That’s when the season can feel oppressive; like it or not, this oppression is also a major, mirror-image theme of the holidays. Maybe that’s why, when I think about Christmases past, my mind is often steered past ornaments and office parties and egg nog, back toward an image of myself in New York in December 1991, when I came to the city by myself to find an apartment for the first time. It's an image that was scary while it was happening, but which I look back on with a sort of head-shaking pride, the way you can when you know how things turn out. It's the kind of pride that says nothing more than, Wow,that was me.

I had finished college the previous spring and was coming to Manhattan to do an internship at Rolling Stone magazine. I’d sent at least 50 resumes out and received exactly one reply, but it made sense in a way—during my freshman year in college, I’d discovered a set of red bound-leather volumes deep in the library that contained every issue of Rolling Stone. I went through them all in about a month. I may not have known Coleridge as well as I should have, but I knew Rolling Stone.

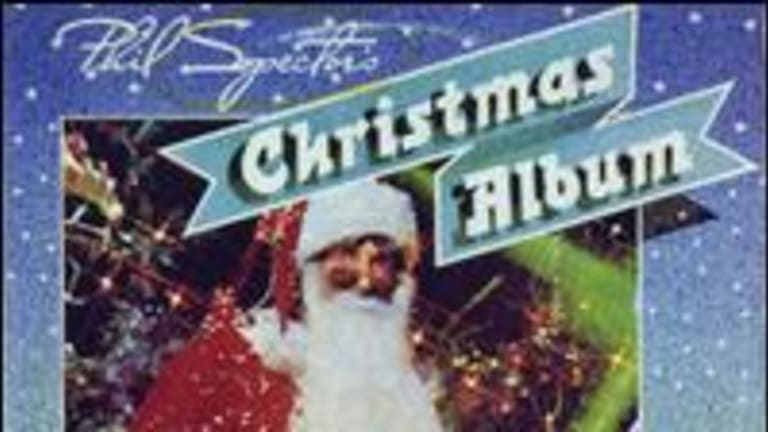

I also knew music, and for the trip to New York I had brought a mix tape—yes, a cassette—of various favorites songs of the moment. The one that stood out as I traipsed up and down Manhattan through a bone-rattling wind, looking at a series of comically miniscule living spaces, was Darlene Love’s “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home).” Recorded in 1963 with Phil Spector’s booming wall of sound, the song has become a kind of national anthem of the holidays over the years. Love sings it every year on the David Letterman show before Christmas. Back in ’91, I’d known it was considered a classic, and I loved Spector’s famous Xmas album. The copy I own features the Great Weirdo himself awkwardly hunched in a Santa suit. But my favorite image is on the back cover. There, at Spector’s feet, is a teddy bear wearing headphones and sunglasses and reading the Bible—I can’t think of anything that better sums up the pop heart of Christmas in America.