Disagreement is the name of the game in tennis, however far and wide you travel. I was sitting in a coffee shop a few mornings ago near Melbourne Park, happily attempting not to think about the sport for a few minutes, when I heard two American women at the next table discussing which matches they wanted to see at the Australian Open. They, of course, couldn’t agree on anything. They had very strong, and very contradictory, opinions about each player who came up.

“Did you see the hideous dress she was wearing?”

“He’s totally obnoxious.”

“That screeching.”

“He’s fun to watch, but I know you don’t like him.”

Finally, they found someone upon which they could both nod their heads in unison.

“We have to go see del Potro.”

“Definitely.”

There’s something about Juan Martin del Potro that tennis fans and player and writers and commentators like (actually, I do know one person who doesn’t dig the Argentine, but I won’t reveal her name here). He once had bad hair, and he used to take an interminable amount of time to decide whether he was going to challenge a call. But absence has made the collective heart grow fonder. Everyone feels for a guy who had a massive career breakthrough at the 2009 U.S. Open only to see his career go up in smoke for a year. Del Potro said he was stunned by how many get-well messages he received from fellow players.

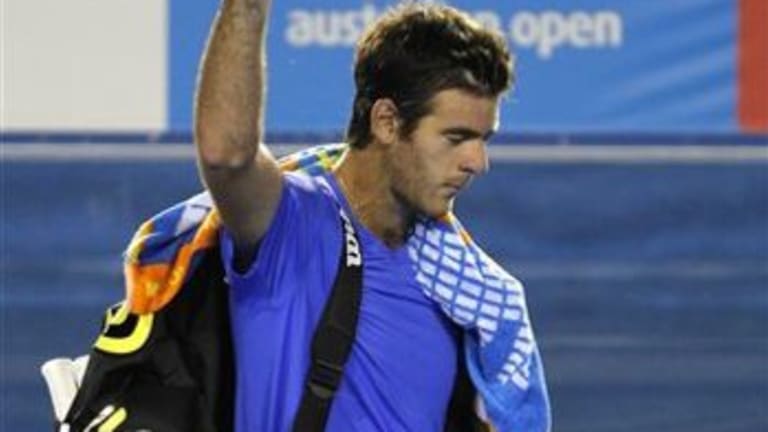

The sympathy didn’t stop with his colleagues. I was watching on my monitor in the press room last night when del Potro’s racquet flew out of his hand, and it looked for a second like his surgically repaired wrist was about to become unrepaired (it didn't). The Channel 7 commentators, Jim Courier and John Fitzgerald, sounded crushed for him. I would have been crushed for him as well if something had gone wrong. He’s the kind of guy you can feel crushed for.

Del Potro’s appeal rests with his transparent yet dignified emotionalism. He doesn’t wear his heart way out on his sleeve, but there’s no hiding how he feels, either; how many other tennis players can express melancholy? The Argentines are high strung as a group, and they very often let their emotions get the better of their games. Yesterday David Nalbandian seemed dead set on staying as enraged as possible for as long as he possible after someone in the crowd disturbed him as he was hitting an overhead. Nalbandian never recovered. He lost seven straight games and retired—due to annoyance, it seemed, as much as anything else—in the third set against Ricardas Berankis.

There are days when del Potro seems to shrink from the battle and even mope—Davis Cup final 2008, final of the World Tour Final 2009—but for the most part he puts his emotions to good use. Rather than hop off the court and pump his fist and stare at his coach after the first game, à la Lleyton Hewitt or Gael Monfils, del Potro stays quiet, broods, stews, and then lets loose with a furious display. Some nights he waits too long to rev himself up. Even in his U.S. Open win, it took him nearly two sets to show anything; he was almost done before he dug himself into the match. The same was true last night. Del Potro had break chances in the first set, but that’s where the rust showed. He couldn’t finish them. He seemed tentative in general at first, but by the third he was fully into it. More important, though, the rust showed in his movement. Whenever del Potro gave his opponent, Marcos Baghdatis, any kind of angle, he was toast. Baghdatis had him coming and going, crosscourt and down the line. Del Potro couldn’t catch up to either.

Del Potro’s long road back has begun. I thought it was promising. He at least looked like the same player, with the same strokes and same heavy power, and he can still get around a tennis court pretty well for a big guy. I’m sure he wondered whether he would ever do any of those things again during his time away. We can all agree—it’s a start.

The man who ended del Potro’s beginning, Baghdatis, looked sharp and . . . light. He’s dropped a few pounds, and it shows. He’s always had the timing. If he’s getting to the ball half a step earlier, the way he was tonight, that ball-striking ability will make him dangerous. His next match, against Jurgen Melzer, should be an entertaining one. It’s also a winnable one. Then he would face Andy Murray. Baghdatis’s Cypriot support has been out again in 2011. Whole families will come to see him, not just young rowdies—though there are plenty of those in attendance. Baghdatis says it’s like playing “in his kitchen,” with the extended family all around. It would be nice to see him get cooking here again. Baghdatis does wear his heart on his sleeve, but as with Juan Martin del Potro, most of us can agree: We want to see him doing well.