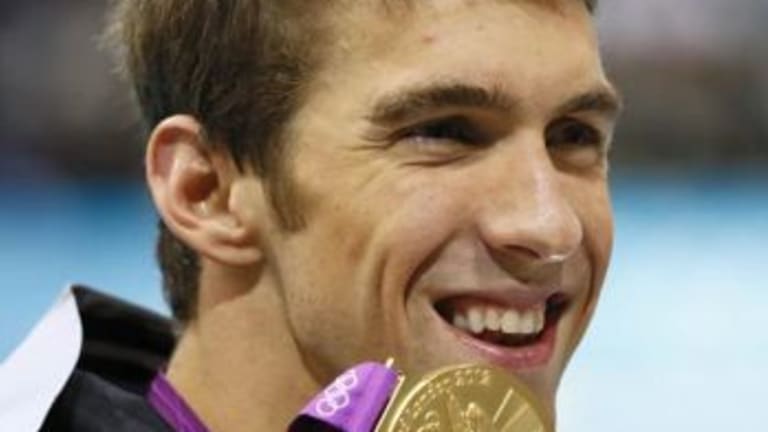

This week, whenever I’ve heard Michael Phelps being interviewed after his races, I’ve been reminded of Roger Federer. This isn’t because the two men sound all that much alike. Phelps appears to get tongue-tied when asked to describe what he does in the pool, or how he feels once a race is over. These were the words he used to sum up his emotions after he won his record eighth gold medal in Beijing in 2008: “It’s something I’ll never forget.” (Really, are you sure you want to go that far out on a limb?) Federer, on the other hand, tends to ramble, and has been known to end up with his foot in his mouth. What unites them in my mind is that these two athletes, who may be the best their sports have ever seen—Olympian is the only word for both of them—are doers, not speech-makers or analysts. They express themselves so thoroughly when they play and swim that there’s nothing else that needs to be said, or can be said.

Federer and Phelps, each of whom has had a starring role in London this week, have more in common than just excellence. Personality-wise, they’re both a mix of the supremely confident and the slightly awkward—aside from a bonghit or two (or more) by Phelps, no scandal has been attached to their names. In terms of their careers, each can fairly be called aging: Phelps is 27, Federer is nearly 31. Each made his first Olympic splash, and fell in love with the Games, back in Sydney in 2000. This year each of them has noted, wistfully, that he’d love to be able to recapture the feeling he had then, but that things change. Federer has hinted that the Olympic spirit may be enough to keep him in the sport until Rio in 2016. Phelps claims that this is his final Games, though last night, while he was trying—again without much success—to describe how he felt about swimming the last Olympic semifinal heat of his career, he seemed to waver on that vow just a little bit. NBC commentator Rowdy Gaines says he thinks that Phelps will get bored sometime in the next few years and change his mind. With four Grand Slams to play for each season, it will certainly be easier for Federer to keep his head, if not his body, in the game until 2016.

Federer and Phelps both came to London with younger rivals at their heels, rivals who, at various times, have appeared destined to pass them for good. As recently as two months ago, Federer was ranked No. 3 in the world, hadn’t won a Grand Slam since 2010, and had watched the two best players from the next generation, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic, contest the last four major finals. As for Phelps, after a few years of indifferent training, he had ceded the spotlight to his fellow American, and omnipresent cover boy, Ryan Lochte. When Lochte won gold in their first showdown and Phelps finished fourth, Federer may have felt a sense of deja vu about the general reaction. Suddenly, Lochte was the new great U.S. swimmer, the future of the sport, the man who showed that Phelps was mortal after all. A couple of days later, Chad Le Clos, a younger swimmer from South Africa who Phelps has, in the words of the New York Times, “seemingly tapped as his successor,” did what the American had done to so many others, tracking him down and out-touching him for gold in the 200-meter butterfly. It seemed that even Phelps’s formerly airtight legacy could be in danger of being damaged by his London Games' performance.

Federer’s version of Lochte and Le Clos are Nadal, Djokovic, Andy Murray, and, today, Juan Martin del Potro. All four are younger, and all use solid baseline games with two-handed backhands, a style that has long been predicted to be the future of the sport. Each time one of these players has beaten Federer, there’s been talk of his decline, and how his one-handed game is outdated.

While Del Potro overpowered Federer in the 2009 U.S. Open final, this year Federer, as he said yesterday, has “had his number,” beating him all five times they’d played. But from the first points of their semifinal on Friday, it was clear that this was a different del Potro. His shots sounded heavier; it looked like he would power his way into the gold-medal match. While he didn’t do that in the end, del Potro may have done something greater by showing the world how much heart he could muster while playing for his country, and how much the Olympic Games have inspired the tennis players of this era. In what would turn out to be an epic 19-17 third set, and perhaps the best match of 2012 so far, del Potro never gave in mentally. He came up with shots and gets and diving volleys that I had never seen from him before. He was also the picture of tennis intensity throughout. The emotional Argentine was working so hard through the third set that it looked as if he were on the verge of tears. It was, in truth, a pained grimace of concentration and will.

As happy as I would have been to see del Potro go for gold—it would have capped his agonizingly long comeback from wrist surgery—I had trouble imagining Federer receiving, or accepting, a bronze. It would have been as strange as the sight of Phelps standing below Lochte on a medal stand. Federer had the crowd behind him on Centre Court today, as he almost always does, and I think part of that is a desire among sports fans to see a legendary athlete’s story end the way we think it should end. I feel the same way about Phelps. I’m sure there are plenty of swimming aficionados who are tired of his dominance and want to see him brought down a notch, just as there are those in the tennis world who have grown weary of Federer’s lionization. But as an outsider to swimming, I want to see the king of the pool remain on his throne. I want to see him crush all of the young punks and challengers, because...because why, exactly?