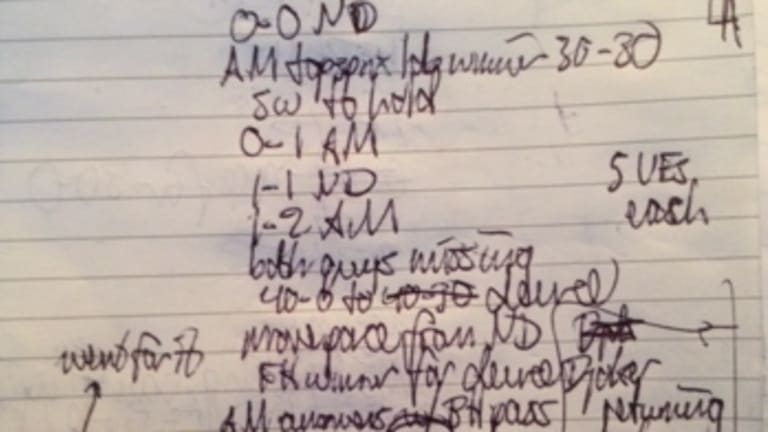

What do you do when you watch a tennis match? Lean forward, bite your fingernails, flip through a magazine, tweet every thought that flits across your brain? Me, I put a pen in my left hand, press down hard, and scratch things like this into a notebook: “FH DTL winner BB”; or “SW SS to save”; or “bad BH UE net 30-30.” It took me years to make these scratchings so succinct. The problem is, sometimes they’re so succinct that the meaning itself is lost to me when I try to decipher them a few hours later.

This is called, in tennis-writer's lingo, Keeping Score. Everyone who reports on a match must do it in some form or another, a fact that I learned the hard way years ago when a veteran journalist asked me at the French Open how many break points Marat Safin had had in one particular set. I flipped back through my notes, which included many incisive comments about the play and the clay and the leaves in the trees and the police sirens in Paris . . . but not a word about break points.

“Three or four?” I ventured tentatively.

The veteran journalist blinked. Obviously, this vague piece of information was of absolutely no use to him. I could hear him thinking: Does this kid really expect me to write, “Safin had three or four break points” in the newspaper and keep my job? What's next, “The match might have gone five sets”?

At that moment, a voice boomed from the row behind us. “It was FOUR! He had FOUR break points!” This outburst came from another, crankier, veteran tennis writer, one who had heard us talking and who was disgusted that someone in the press room didn’t know how to keep track of friggin’ break points.

Since then, I’ve done my best to know exactly how many break points, set points, and match points each player has. I’ve also tried to keep a general idea of all of the other things a tennis writer is supposed to have a general idea of—first-serve percentage, unforced errors from the backhand side, number of net approaches, racquets cracked, seconds taken between points, ball kids cursed. But I have to admit that some of this information slides past me. I still like to write about the leaves in the trees, and the fans in the stands, and whatever else comes to mind, when I can. (And you can see above, I get ideas when I'm taking notes, like the idea for this piece, which is noted inside it very own square, "Scoring a Match.")

Every writer has his or her own way of keeping score. Unless I missed it, there were no classes to teach you how. Some go for mathematical precision; a match, whatever emotional upheavals may occur over its course, ends up as a neat and clean chart in their notebook. A few are more loquacious, scribbling entire sentences of God’s knows what after every point. Some are literal; one year at the U.S. Open I sat behind a New York sportswriter, who didn’t normally cover tennis, who made this observation in his notebook, “There must be a dozen women in Kuerten’s players’ box. Are they all his girlfriends?”

Others are abstract and artistic. One Japanese journalist writes in symbols. After each point, he scrawls a circle, or a triangle, or a square, or another regular shape. I imagine that by altering their size or position he can embed them with a number of pieces of information at once—an upside-down triangle might be the sign for a topspin forehand crosscourt winner on the run. It would certainly be less work than my “FH CC OTR winner.” I don’t know, though; I’ve never asked him. And I would never remember what the symbols were supposed to mean if I tried.

Fortunately, doing a post on a blog, rather than an article in a newspaper, has meant that I’ve been able to get away with a certain amount of inexactness—kind of like being able to write that Ryan Harrison is a “teenager,” so you don’t have to look up whether he’s 18 or 19. (Unfortunately, all players, including Harrison next year, stop being teenagers; reporting that someone is “in their 20s” doesn’t really cut it, even on a blog.) I’ve been known to backslide occasionally, when I can't decipher my own writing, and report that a player had “multiple” break points in a particular game. To combat this, and avoid having veteran journalists in the next row scream in my direction, I’ve taken to writing "BP" or "SP" or "MP" and circling it—very crafty.

I would say that I’m at my best in tiebreakers, which can be easily turned into charts that allow you to record what happened on every point. I’m at my worst early in second sets, when my guard is down. I often come out of them thinking hard, “Now what happened there?” The rise of the Racquet Reaction has made basic factual information seem more important; the RRs are as much news as they are analysis or opinion. (Actually, as you can see above, I may be at my worst when I'm doodling. I've never gotten past the "make a square look like a box" phase that was such a revelation in 2nd grade.)

Is keeping score a chore? Not once you get used to it. It brings you inside a match, and makes you think about it in a way you normally wouldn’t. You have to be alive and attentive to all of its possibilities, all of the various ways that it could go. When you are, you realize how quickly a match can turn, how little things add up, how seemingly innocuous early points and errors can loom much larger later, and how a result appears to be foreordained afterward often could have gone either way—you see the match piece by piece, scribble by scribble, blown break point by blown break point. You realize that there are a lot more "big points" than you might think, and that they can come when you least expect them.

For instance, the first set on Sunday between Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray, which was won by Djokovic 6-1, appeared to be a blowout. And it was. But looking at my notebook above, provided you can make heads or tails of it, you can see that it might have gone a different way if Murray had been able to get out his five-deuce service game at 1-2. He saved one break point with a service winner, then hit another to earn a game point. Those two shots could, potentially, have begun an entirely different narrative for the match, one about Murray being able to "serve his way out of trouble" or "find his best when he needed it." But that's not how it went. Instead, Djokovic, the master returner, wore him down and began writing his own story. He broke serve by cracking a backhand down the line and taking over the rally from there. Or, as I noted at the time, “breaks by opening up w/ BH DTL.”

It was a signature Djokovic shot, and a moment to remember if the match went his way. If only I’d been in the press room afterward, instead of my living room, and another writer has asked me how it all happened . . .