PARIS—There are exciting days in tennis, and then there are days like this, when you don’t know where to look. The French bamboozled us again by scheduling the two men’s quarterfinals—both of which looked like blockbusters—at exactly the same time. I spent much of the afternoon flicking my eyes from one screen to the next and back again. There was one moment when Novak Djokovic and Roger Federer faced crucial break points at the same time; their service motions were perfectly in sync. Later, Federer and Jo-Wilfried Tsonga held simultaneous match points. What can a tennis fan do at a time like that?

I did get out to both courts long enough to feel the atmosphere of two dueling French audiences. One got what it wanted (even if it didn’t make the object of its obsession happy the whole time), and the other didn’t. After all of the chanting and booing and “Allez!”s, and the bittersweet cheers for their countryman as he hid under a towel, it was Federer and Djokovic who survived again to reach yet another Grand Slam semifinal. Here's what their wins felt like.

The crowd inside Court Suzanne Lenglen isn’t cheering for a countryman. It’s cheering for an idol, a man referred to by at least one Parisian this week as “Jesus.” If anything, this makes the fans more obsessive and intense. A French player is a family member, someone you love and occasionally hate, someone you’ll support and defend at most times, but who you can also scold and jeer if they let you down. Federer isn’t family; nor is he like a favorite local French sports team. He’s something more here, something more distanced and inarguable. He's the Truth.

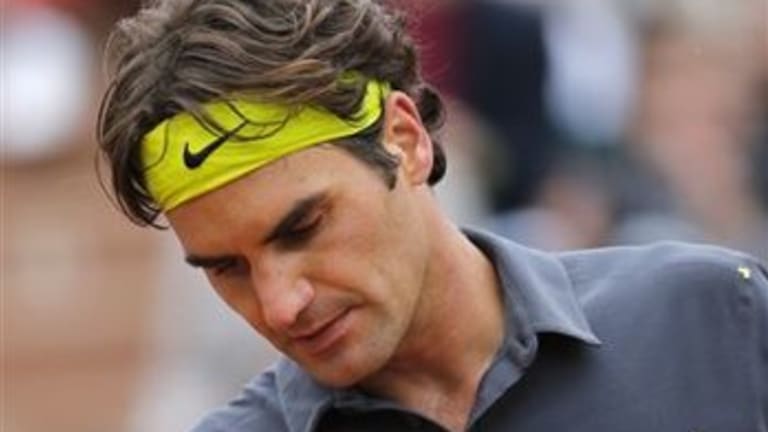

At the moment, late in the second set, the Truth is losing. Federer is trying everything against his hot-hitting opponent, Juan Martin del Potro. He's scrambling and stabbing balls back as only he can. Federer has roused himself from a sluggish start, and gone up a break in the second set, only to give it back. He's beaten del Potro on hard courts four times already this year by using his chip and his drop and getting the tall Argentine out of position along the baseline. Today, though, he’s mostly trying to belt with del Potro, to come over his backhand and push him off the baseline with his forehand. The match has the feel of the one they played in the 2009 U.S. Open final. As in that one, from up close you can get see how del Potro's knocking Federer onto his back foot. Before the match, the Argentine, who is nursing a bad knee, said that his strategy was to, “try to play an unbelievable match.” As the second set heads toward its conclusion, his plan is working. He has his own loud fan base here, and like him, they're holding their own.

It's the second point of the tiebreaker, and del Potro lasers a flat forehand crosscourt as hard as any ground stroke that’s been hit at this tournament. The points now have a desperate quality; each man knows that the longer the match goes, the better Federer’s chances are. Del Potro is, for lack of a more original phrase, hitting the cover off the ball, from both sides, in both directions. Federer is fighting for his life on defense; half of his shots appear to be blind stabs, but he wins rallies with them. Late in the tiebreaker, Federer does something that he rarely does: he grunts. Late in the tiebreaker, after he’s lost a point in which some noise was made on a close call midway, Federer does something even more surprising**: He tells at least one member of the Lenglen crowd—a crowd that’s much closer to the players than the one in Chatrier—to “Shut up!”

Asked about the outburst later, Federer says he felt like he should have won the set earlier, and that he was frustrated to be “stuck in a breaker,” when “Juan Martin is playing well, hitting hard, and I’m on defense.”

“Obviously I was emotional,” Federer continues, a bit sheepishly. He has not only told someone in his most devoted audience to shut up, he’s done it in English.

“I was, you know, sometimes upset,” he concludes.

Federer loses the tiebreaker, but it’s del Potro who is somehow deflated. He immediately begins to slow down as the third set begins. He loses his first service game on a double fault, and hangs his head as if it’s him, rather than his opponent, who is down two sets. Del Potro will win just five more games, as Federer takes control of the rallies and mix up his serves. He wins the fourth set 6-0 in under half an hour.

Federer, relieved, is expansive in his analysis later. “I knew it was going to be tough,” he says. “I've still been struggling to find my rhythm. [I was] trying to figure out how to play a guy who returns from so far back on a slow court. Do you try to serve through him? Which I tried—didn’t work. Or do I try and move it around a little. And that worked a bit better, but it was really in the mix-up that I found success.”

As for del Potro’s drop off, it remains a mystery. Pressed on whether his knee affected him, he refuses to bite: “No,” is all he says. He chalks the loss up to his poor serving, and Federer’s improvement, yet del Potro took a painkiller at the end of the second set, and there were moments when he wasn’t running for routine shots. And while he was blitzed off the court in the fourth, he came back and competed in the fifth. An Argentine journalist who knows del Potro says this is one of the few times that he has no idea what happened to him.

Asked what he’s going to do next, del Potro says, “I’m going to rest.”

Asked about his upcoming semifinal with Djokovic, Federer speaks for both of them, and for us. “We’re looking forward to it,” he says. The truth, from the truth.