There’s something sinister about the sound as it goes up in Hisense Arena. It’s the famous “Aussie! Aussie! Aussie! Oi! Oi! Oi!” chant, which we know so well. But this time the first part of it, the Aussie part, is being chanted by a group of children, while the adults around them follow with the second part, the Oi part. It’s part Village of the Damned, part Chinese Cultural Revolution, part “Another Brick in the Wall.” And the evil children shall lead . . .

No, there's nothing really evil about it; this is Oz, after all. The Australian Open is the most modest of the majors—size and atmosphere wise, it’s midway between the U.S. Open and Key Biscayne—but it's also the most spirited. Wimbledon and Roland Garros exude history; the U.S. Open exudes cash; Melbourne Park is a sporting event in a purer sense. The Aussies bring a festive partisanship to tennis that doesn’t exist at the other Slams. As the first week ends, here’s a tour, in words, of what those festivities look like.

*

Rod Laver Arena is the easiest main Grand Slam arena for watching tennis. At Ashe Stadium, you have to lug binoculars along. In Centre Court, you have to fit yourself into a seat made for approximately two-thirds of a human body (or maybe that’s just an American human body). And there’s a certain nerve-wracking energy to Court Chatrier at Roland Garros. Laver is a kind of steel version of Centre Court, without the history, but with the comfort. There are no luxury suites. This gives the arena a more unified feel than Ashe, which is so conspicuously split between the haves in the lower bowl and the have-lesses stranded in the nosebleeds above the double rows of corporate boxes. To accommodate the retractable roof here, there’s a large overhang around the top, which is also reminiscent of Centre Court. It creates a similar echo when the ball is struck.

As with all the majors, the audience hierarchy begins at one end of the arena. At Wimbledon, this is the Royal Box. At the others, it’s where the national federation reserves the house’s best seats for suited luminaries. These seats are often empty at Flushing and Roland Garros, but that hasn’t been the case here. The suits are late arriving, and they tend to hold up play while they find their way to their seats, but they do watch. And there’s no special, exclusive look to their section. Unlike the President’s Box in Ashe, anyone can walk into its vicinity. The fashion on display at the high end of Laver is closer to Wimbledon-dignified than the celebrity flash of the U.S. Open.

From there, the pecking order descends gradually with each section as you curve around the arena. Next up are the corporate boxes, filled with beer-sipping young men in jackets, jeans, irritatingly large shoes, and rectangular eyewear. Next it’s the press section, which has a sizable number of bearded Europeans staring into laptops. Right after that you find the Aussie tennis elite. Pat Rafter and family, Fred Stolle, Tood Woodbridge, Rennae Stubbs, the player’s boxes, the sport’s well-known agents and TV personalities—they congregate here, along the baseline.

Finally you get to the long middle, which stretches down the sideline. In New York, these are also corporate boxes, but here they seem to be open to the great unwashed. Or the great sporting middle class, however you want to put it. Golf shirts and sun dresses mix with bands of people painted green and gold. Patriotism is still cool in this land of just 21 million. Even in the big house here, it’s not gauche or politically incorrect to shout, “Let’s go, Aussie!” I have trouble imagining shouts of “Let’s go, Yankee!” passing muster in Ashe.

*

The side courts stretch back through a long and gradually narrowing triangle that reaches almost into downtown Melbourne. Together, the courts create a sea of light blue that can feel like an oasis on a sweltering day. Their best attribute is the grass that grows around them—good for a stretch in the sun when you’re work is all done. On the other side of the grounds is Hisense Arena, a giant, airy, tech-y, modern steel box where you’re protected from the sun, but also from the excitement of the tennis. The seats are just too far away to give you a visceral feel for what’s going on down on the court.

The beery spirit of Melbourne Park can best be caught not in the biggest arenas or the smallest side courts, but in the three mid-sized show courts that make up the core of the grounds (the U.S. Open wants to construct a set of courts like these in the future; for once, the Aussies are leading the Yanks in the pro game’s evolution). These are best experienced in the late afternoon, when the sun is fading and you want to settle down somewhere after roaming the grounds all day. People find empty spots where they can sprawl with their legs up on the seats in front of them, and their arms stretched out on the seat-backs next to them. Baseball hats get turned sideways and pulled low to shade faces from the sun. Watching tennis and getting a tan take equal precedence. The match, whatever match it may be, becomes a means to relax, to unwind before you call it a day.

Do the Australians know their tennis better than Americans? I have heard seemingly normal, well-adjusted humans commenting on the personal life of Stan Wawrinka and the highly emotional nature of “all the Argies.” One person they know well is John Isner—I’m starting to think he's now more famous than Andy Roddick. On Saturday afternoon, with my work done and the sun going down, I climbed into Margaret Court Arena. Despite the name, it’s identical to the generically labeled Show Courts 2 and 3. This time the seats were full; no one could sprawl. But the atmosphere was ideal as Isner and Marin Cilic went through their long, languid, seemingly endless five-set duel. There were few chants this time, just sporadic cries for Isner, the folk hero.

Here was tennis at its most fundamental. Every seat was taken. The stadium was big enough to give you a sense that you were part of something vast and important, but small enough that everyone could take part in it. The two players looked, as they should, like lonely warriors in front of us, but we were connected to them as well. The match went in the old fashioned way—service holds were expected, and most were routine, but there was always the possibility, with a single error or misplay, that the match could be over in minutes.

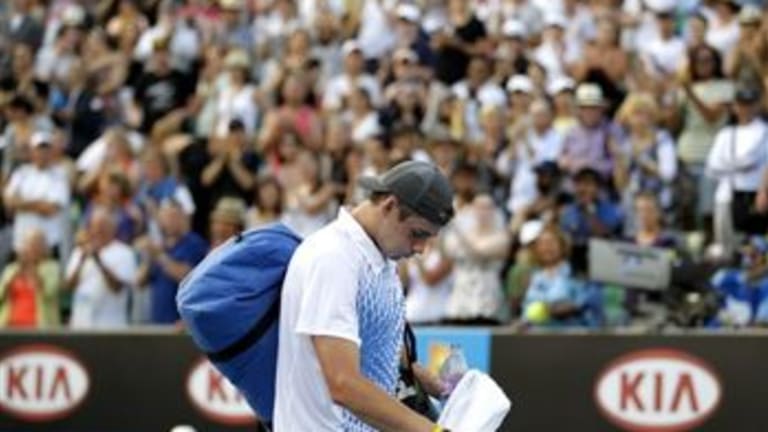

Isner and Cilic were mirror images. Isner the folk hero kept us absorbed in an odd way. He has a sort of anti-charisma. He appears to be dead—or “flat” as the Aussies say. He walks slowly. He breathes heavily. He puts his hands on his knees. He shanks balls horribly. But at the same time he’s right in the match. You root for his struggle, even if you don’t love his style. As Andy Roddick said this week, it seems like Isner plays the same match over and over and over. This time he lost it.

For me, from the U.S., watching a match like that in the afternoon Aussie sun has a surreal quality. Part of me is still at home, thinking of everyone in the States asleep at 4 A.M. while this is going on in broad daylight. I’m stealing some sun in the dead of cold winter. What more can you ask from a tennis tournament?