They Said What?

Unpacking the WTA's desire for equal prize money, and a possible deal with Saudi Arabia

By Jul 08, 2023They Said What?

Luca Nardi defeats Novak Djokovic: Teachable moments from a stunning upset

By Mar 12, 2024They Said What?

Are we witnessing a new Daniil Medvedev?

By Jan 25, 2024They Said What?

Dayana Yastremska's racquet is doing the talking at the Australian Open

By Jan 22, 2024They Said What?

Deciding when to retire is a unique case for tennis players. Just ask Andy Murray

By Jan 18, 2024They Said What?

Roger Federer may not be tennis' GOAT, but as Rafael Nadal articulated, he's a 1 of 1

By Jan 06, 2024They Said What?

The lingering debate on tennis balls used at ATP and WTA tournaments is a ball of confusion

By Oct 08, 2023They Said What?

Will Ash Barty be the next big tennis name to un-retire?

By Oct 06, 2023They Said What?

Simona Halep's suspension is the latest example of tennis' unsatisfying anti-doping efforts

By Sep 27, 2023They Said What?

On the scale of self-awareness, Carlos Alcaraz was a 12 out of 10 after US Open defeat

By Sep 11, 2023They Said What?

Unpacking the WTA's desire for equal prize money, and a possible deal with Saudi Arabia

Leaving no stone unturned, the WTA may depart sharply from the way it has always done business—and into controversial partnerships.

Published Jul 08, 2023

Advertising

Jessica Pegula and other players on both tours believe a business deal with Saudi Arabia could be in the best interest of the sport. Other prominent names in tennis aren't as convinced.

© ©AELTC/Florian Eisele

Advertising

Whether the WTA can effect change in Saudi Arabia, or many other parts of the Arab world, is questionable at the best of times. In February, CEO Steve Simon and other tour board members visited with officials of the Public Investment Fund.

© Getty Images

Advertising

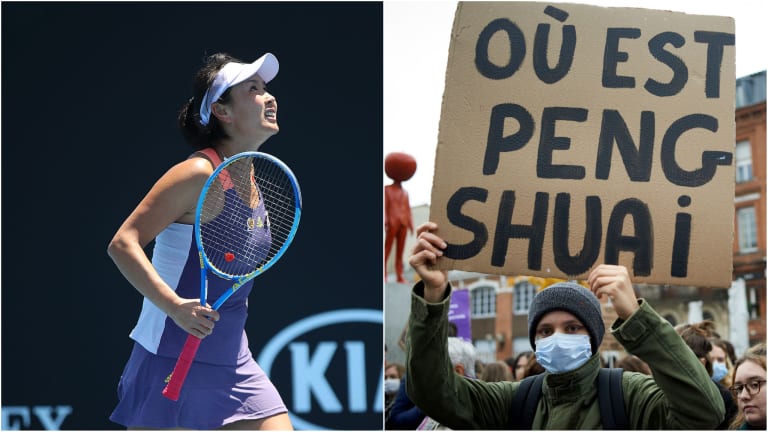

The disappearance of Peng Shuai, and a subsequent lack of assurance about her well-being, has been a major issue for the WTA, with financial consequences.