First in a series on great tennis books that I've recently discovered (no, I don't mean the one pictured at right).

As I’ve mentioned over the last few months, I’ve been writing a book about the men's game in those fabled roughneck 1970s and 80s. It’s finished now, and it’s coming out on May 17. When I think about that, what keeps going through my head is the title of a book by John Madden. Back in his buffoonish beer-commercial days, he published a searching memoir entitled, Hey Wait a Minute, I Wrote a Book.

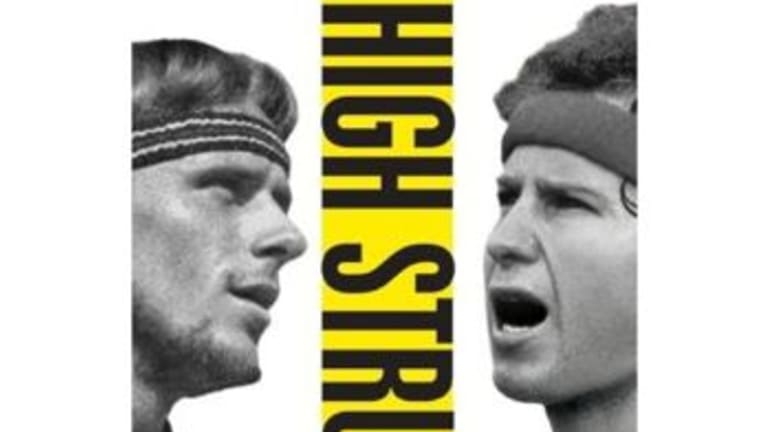

Mine is called High Strung: Bjorn Borg, John McEnroe, and the Untold Story of Tennis’s Fiercest Rivalry. The title is narrower than the subject matter. The book is really a look, through the lens of the 1981 U.S. Open, at the era of men’s tennis that ended at that tournament. It takes a snap shot of the lives and careers of the four semifinalists—Borg, McEnroe, Jimmy Connors and Vitas Gerulaitis—as well Ilie Nastase, who was in rapid descent at that moment, and Ivan Lendl, who was in rapid ascent, and who represented the game’s future. Through these guys we hopefully get an idea of how much the sport had changed in the previous decade, and what it had done to the players, both good and bad. (You can pre-order it here.)

I didn’t do much but write the book for a period of about six months, finishing it while I was at the Australian Open. It got to the point where I would see people watching football on weekends and wonder what they were doing with their lives, why weren’t they working on Sunday afternoons? As much writing as was required, there was equally as much reading. I wrote a fair amount about the history of tennis, especially in the United States, which meant making my way through stacks of tennis history books and magazine and newspaper articles. I was amazed by much I didn’t know, even about people and players and events of which I was familiar. Which only makes me realize that there’s still a ton more I must not know.

The upshot is that I gained a profound new respect for tennis writing in general. This is not the popular opinion, even among lovers of sportswriting. George Plimpton dismissed tennis writing as fuzzy and fizzy. In an interview with the New Yorker, Jon Wertheim was asked the usual question, “Why isn’t there more good tennis writing?” Wertheim mentioned David Foster Wallace, of course, and put in a good word for Bodo’s Borg piece that I talked about last week, and . . . that was about all he could come up with.

Wallace is beloved by literature fans because he brought a frenetic modern highbrow sensibility to tennis; he made it seem kind of hip, in an extremely nerdy way, of course. But that isn’t the only way to write about the sport; it’s also not possible to do on a regular basis. Part of the appeal of his pieces was that he was dropping in on the tennis scene and giving us an unjaded outsider’s macro-eye view of it. There’s no way he was going to produce something like his 10,000-word take on the U.S. Open that he did for Tennis Magazine in 1995 on a regular basis.

Nor is it necessarily the best way to write about it. As much as I like Wallace, I’m not sure he could have written a book that was as enjoyably informative and addictively readable, to me, as My Life with the Pros, a memoir by Bud Collins. Bud will never be studied in a literature class, but he strikes the right, light tone here.

Last summer, at the men’s tournament in Toronto, I visited my friend and fellow tennis journalist Tom Tebbutt’s house. He has a fantastic collection of wood racquets from all over the world, and a smaller but to my mind equally good collection of tennis books. Looking at the aging collections of the correspondents from the big British papers, a tennis writer today can allow himself to feel like he’s part of a tradition (one that doesn’t really exist in the U.S., where there have been far fewer writers dedicated to just this sport). One American name that popped out at me on those shelves was that of Al Laney. I knew he had been the tennis writer for the New York Herald for decades, and that he and the Times’ Allison Danzig were the big names in amateur-era tennis writing. Fittingly, Danzig retired as the Open era began, in 1968, the same year that Laney published his memoir of his days on the tennis circuit, Covering the Court.

Tom was surprised that I’d never read Covering the Court. He happened to have two copies, so he lent me one, which I still have. Laney, in first-person remembrance, focuses primarily on tennis in what for him were its most glorious years, the 1920s of Bill Tilden and Suzanne Lenglen, but there are interesting observations up through the 1960s. I’ve tried to read the Frank DeFord biography of Tilden but found it a little dry, and I’ve tried to read The Goddess and the Golden Girl, a book about the Lenglen and Helen Wills Moody, only to find its length and exhaustiveness daunting. But Laney’s way of telling those same stories, through his own recollections, brings them to life in a way that those two books never do.

This is because Laney is, first of all, a tennis fan. He’s very good at describing how his feelings about the top players change with the years. His first hero is Maurice McLoughlin, the California Comet, whom he watches as a kid in the Davis Cup in 1914. McLoughlin, the first champ raised on public courts, made tennis a national sport. But as his name implies, he burned out quickly. Laney sees him again five years later, at Forest Hills in 1919, and sees something different in him:

I had strange, mixed feelings as I watched McLoughlin through a series of early matches, one of them on the same court where he had been so luminous a few years earlier. He was the same dashing figure and I could see nothing outwardly different. There was the same dynamic service and overhead play with which he had thrilled Forest Hills in 1914. The relentless years had not stood still for him, though, for I had heard everywhere that the old California Comet had declined and had read that he would probably retire after this season.

Strangely, this knowledge did not disturb me as I thought it should. I had seen him in his glory, but what had been concealed from the schoolboy’s eye was now revealed. Now I realized that both Brookes and Wilding could have beaten him on tennis alone but could not withstand the inspired outbursts that made him godlike, with the light of heaven flashing from his racquet.

That light is extinguished for Laney, who sees more clearly with age. Through McLoughlin, too, the writer gives us an idea of how much had changed in the world during those five years, the years of World War I. Everything is different at Forest Hills in 1919; the old world of tennis, of Newport and society, the world that McLoughlin had helped shatter, has vanished. There’s a new hero rising, Bill Tilden, and Laney can’t stand him. He first encounters him on a back court that year, bossing around a group of photographers.

Tilden was in charge, telling them exactly how they should do their work. He was not to be champion for another year, but already he was acting the part and a little more. . . . It was a face on which no expression of humility seemed possible; there seemed to be a conscious feeling of superiority. I thought as I watched that I had never seen such arrogance, and such distasteful mannerisms. This was not in the tennis tradition I had pictured to myself. It definitely was not in keeping with the past.

Laney goes on to chronicle the 1920s, the Era of Wonderful Nonsense, in his words, which peaks in 1926 with the Lenglen-Moody match in Cannes. He describes the build-up to the match as temporarily blotting out all other worldwide news (we thought we were frivolous now).

By the time it came off it was of worldwide interest, and never again in the history of sport was such an event allowed to go under such ridiculous and fantastic conditions. It could have filled up Yankee Stadium, but it was played at a not very attractive club of six courts.

Laney’s on-scene description is memorable as well. The area surrounding the club is so completely jammed that the only way he and the other writers make it in is by following a flying wedge made by the photographers on the scene. In the press room, he finds himself surrounded by the world’s best writers, James Thurber included, some of whom have been taken off battlefield beats to cover this womens’ tennis match.

The Musketeers, Budge, Jacobs, Wills, Crawford, Vines, Cram, Gonzalez, the pros: Laney eventually gets around to them, though you feel like his heart is always back in the sport’s early years—two-thirds of the way through the book, it’s still 1939. He makes an interesting point about the barnstorming professional tours, about which he never develops any love, despite the quality of the players. An amateur-era writer at heart, Laney thinks of the pros as somewhat cynical, never playing a meaningful match, willing to play pointless exos night after night. He considers their careers hard to assess because this.

I have covered and written about dozens of professional matches. But it is next to impossible to remember anything significant about them, and with one or two notable exceptions, I cannot find enough detail to describe one of them, as the amateur tournaments and team matches have been recalled. I submit that the principal reason for this is that not one of these matches had any real meaning in the sense of the Davis Cup or amateur championship meetings. They are easily remembered as occasions, but do we really remember them as tennis contests? Did Kramer beat Riggs on the night of the big blizzard at the Garden? I’m not sure he did. Or did he?

Laney goes on to say that he can’t even recall the professional debuts of Rosewall and Laver. This leads him back to perhaps the book’s best moment, the moment when he really does remember seeing Rosewall for the first time.