NEW YORK—Did you happen to know that Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe were rivals once upon a time? You may have heard something about it this year. I wrote a book about it, Matt Cronin wrote a book about it, HBO did a documentary on it, and there’s even been a strange advertising campaign for underwear centering on the two old-timers—can we look for the same thing from Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal in 30 years?

Anyway, my version of the Borg-Mac story, "High Strung," is really the story of the 1981 U.S. Open, and the cast of characters, led by Superbrat and Ice Borg, from that tournament and that era. It was a turning point in the sport’s history, and not just because it was the last Grand Slam that Borg would play. The game itself was changing, and that transformation—from wood racquets to graphite, from the net to the baseline—was summed up in the epic, five-set, fourth-round match on the Grandstand that year between an old-schooler, Vitas Gerulaitis, and the leader of the new school, Ivan Lendl. Two chapters of "High Strung" are devoted to their clash and the personalities behind it. Here’s a condensed version. Hopefully, if you’re on the east coast somewhere, it will be good for a hurricane-ravaged day before this U.S. Open kicks off.

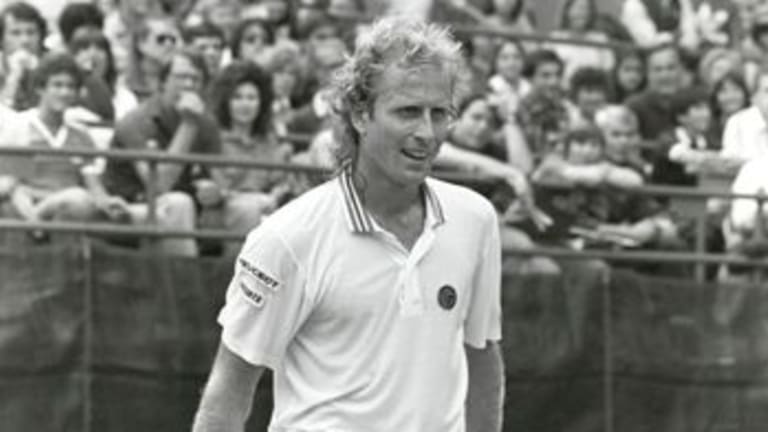

Over the course of his 10-year career, Vitas Gerulaitis has been compared to, among others, Joe Namath, Elvis Presley, and, most often, his good friend and tormentor Bjorn Borg. After his first match at the 1981 U.S. Open, though, Gerulaitis sounded more like one his fellow Brooklyn natives, Vinny Barbarino, the Sweathog played by John Travolta in the hit TV series of the day, Welcome Back, Kotter.

In the obscure outer reaches of the National Tennis Center, Gerulaitis walked off a jam-packed Court 16 after beating Terry Moor in five sets. He was met by his father, Vitas Sr., a tennis instructor who had first put a racquet in his son’s hand, and who had been the first head pro at Flushing Meadows. Senior gave Junior a congratulatory kiss on the cheek. The son thought it was a bit much.

“Jeez, Dad, now it’s a big deal when I win one round, huh?” the younger Gerulaitis said with mock annoyance. “Don’t have a coronary over one match.”

But Gerulaitis was as happy and relieved as his father. “This is the kind of match I’ve been losing,” he admitted.

Up to that point, 1981 had been a lost season for Gerulaitis. For half a decade he had been a fixture near the top of the rankings and a regular semifinalist and occasional finalist at the Grand Slams (he even won a star-depleted Australian Open in 1977). One year earlier, Gerulaitis was the 5th seed at Flushing. Now he had plummeted to No. 15. He came in to the tournament, according to the New York Times, as an “afterthought.” In the less charitable words of the Daily News, he was “a guy who didn’t belong with the contenders or even the pretenders.”

Like his colleagues Ilie Nastase and Bjorn Borg, Gerulaitis had spent much of the 1970s playing and living hard. As a new decade dawned, the candle that he had burned at both ends had begun to burn back. Part of this was the inevitable aging process. At 27, Gerulaitis discovered that he couldn’t maintain his legendary, round the clock, Broadway Vitas pace and still expect to hold it together on the court.

“I took a month off and didn’t practice,” Gerulaitis said as the Open began. “In the past, I was able to take a week off, play around, party, and get by. This time I found out I couldn’t. I guess I just lost my interest in tennis this past year.”

A few defeats early in the season had shaken Gerulaitis’ confidence, and a trip through the European clay-court circuit had been a disaster. “I wasn’t in the best shape and it showed,” he said. “I lost a couple of matches and said, ‘Ahhh, no big deal, I’ll come back.’ I lost a few more and I heard people say, ‘He can’t run anymore.’ Then I got the self-pitying trip. You know, ‘poor Vitas this, poos Vitas that.’”

By the time he got to Germany during that tour, the self-pity had to infect Gerulaitis, though he could still play it for a laugh. Before leaving for Europe, he contacted Robert Lansdorp, a California coach who had mentored Tracy Austin, and asked him to help him with his training. “We went to Germany to play the Hamburg Open,” Lansdorp recalled, “and he was playing this little Spaniard who I thought was a ball boy. Vitas cramped. He finally lost in a tiebreaker and they had to bring out a stretcher to carry him off. As he’s being wheeled by me he looks up and says, ‘Lansdorp, go home. I’m ruining your reputation.’”

It wasn’t just Gerulaitis’s age that had begun to show. While he remained a friend to all of them, inside he had grown weary of his role as an eternal sideshow act to Borg, McEnroe, and Connors. After turning pro in 1972, Gerulaitis had improved and risen steadily until 1977. At Wimbledon that year he reached the semifinals for the first time. But there he ran into the man who became his personal glass ceiling, Bjorn Borg. Year after year, Slam after Slam, when Gerulaitis would make a great run, the Swede would be waiting for him at the end of it. While he had stretched Borg to five memorable sets that day at Wimbledon, a pattern had been set. “I sometimes wonder what would have happened if he had won that match against me,” Borg said years later. “If he had beaten me, his career might have been very different.” It was the first in what would be a life filled with what-ifs and might-have-beens.

Stalled at No. 4, Gerulaitis watched as McEnroe, his Port Washington kid brother, took what he had always desired most, a title in his hometown at the U.S. Open. Finally, in 1980, there had been a breakthrough. At the Masters in New York, Gerulaitis beat Connors for the first time, after 16 straight defeats. True to Vitas’s freewheeling, no-ego style, the win inspired him to the heights of self-deprecatory chest-puffing, while giving tennis a lasting bon mot: “Nobody beats Vitas Gerulaitis 17 times in a row," he said.

Nobody, that is, except Bjorn Borg. Coming into the 1981 Open, Gerulaitis’s record against his friend was a mortifying 0-20. (Today it’s officially listed as 0-16 by the men’s tour; maybe Vitas hadn’t been joking after the Connors match.) Gerulaitis once said that he began every match with Borg with a dozen new ideas about how to beat him, then watched as his nemesis blew each of them to pieces. By 1980, though, Gerulaitis couldn't be philosophical about it any longer. After beating Connors in January, over the next five months he would lose to Borg four times, including a dismal 6-0, 6-2 drubbing in Monte Carlo, and an equally lopsided blowout loss in the French Open final, 6-4, 6-1, 6-2.

“I got to Connors," an agitated Gerulaitis told John Feinstein of the Washington Post in September 1981, “I got to McEnroe, but I just couldn’t get to Borg. It got frustrating. I just got tired of chasing, chasing, not getting there. I took time off because I wanted to get away from tennis for a while.”

But coming back from that break had been hard, and Lansdorp, for one, had been left to wonder how much Gerulaitis’ nightlife had begun to affect his attitude toward the game. “He lied to me,” Lansdorp said. “I would ask, ‘Do you do drugs?’ and he would say, ‘No.’ But then he would disappear on me for a whole week. I’d call the hotel but I wouldn’t see him for two days. I asked him in the beginning but I never asked again. It was my business but it wasn’t my business.”

So far 1981 had been a bust. And there were clouds on the horizon, clouds that would soon grow much darker. But Gerulaitis, who loved to play in his hometown even if it had never loved him back, would make the Open the site of his reclamation, and become the biggest surprise of the two weeks. He followed his win over Moor with two easy victories in his next two rounds. In his straight-set third-round win over the tenacious Harold Solomon, Gerulaitis said he played well enough to "have some confidence finally.”

Even so, it appeared that Vitas’s run would end in the next round, where he was scheduled to face the No. 3 player in the world and the sport’s stony new face of doom, a 21-year-old Czechoslovakian who had already been referred to by Tennis magazine as “the world’s toughest player”: Ivan Lendl. Few recognized it at the time, but their match on a jammed Grandstand court would pit tennis’s past against its future. The 1981 U.S. Open had reached its middle weekend, and the sport had reached a turning point. Was it ready to make that turn?