NEW YORK—Minutes after posting a picture on Facebook of the email, Max Levy got a reply. The email informed him that he had made the cut and been selected as a ball person at this year’s U.S. Open. The reply was from Jenna Loeb, a former coach of his and the sister of Jamie, a top American junior and wild-card entry into the qualifying tournament.

“If you get on my sister’s match,” Jenna wrote, “you better not screw up!”

And how do I know about the Facebook message? Because Max told me about it over dinner.

I am covering my 35th consecutive U.S. Open as a member of the press corps; my 17-year-old son is working his first. Aside from driving out together in the morning and meeting back up at the fountain outside Arthur Ashe Stadium at day’s end, I hardly see him. When I do, when I wander by the court where he is performing his ball person duties (proud mom wanting to bask in the glow of his throwing arm), he doesn’t make eye contact. He stands Buckingham-guard-like in position behind the baseline, hands clasped firmly behind his back, until the point ends. Then, he dashes to grab the ball and throw it down the line, from his end of the court to the ball person on the other end, or else retrieves the throw from the other end—with one bounce, no more—and then tosses it to the player about to serve. Sometimes he hands the player a towel to mop up sweat. He loves every minute of it but never cracks a smile. He wears his game face at all times.

The competition for the job was about as fierce as the fighting one’s way through the food court between matches. Back in June—after warming up by throwing balls across the backyard to our eager dog, Scooter—Max queued up with nearly 500 other hopefuls for one of the 80 coveted spots awarded to rookies. A high school varsity tennis player, he was joined by a wide assemblage of athletes, including baseball, soccer, and football players, as well as former military servicemen and one or two retired people looking for a chance to get up close and personal with the players. The rookies would be added to the 150 veterans who would be back for their second, fourth, or 24th year on the job. While the minimum age to be a ball person is 14, there is no maximum age; this year, one man is 64 years old.

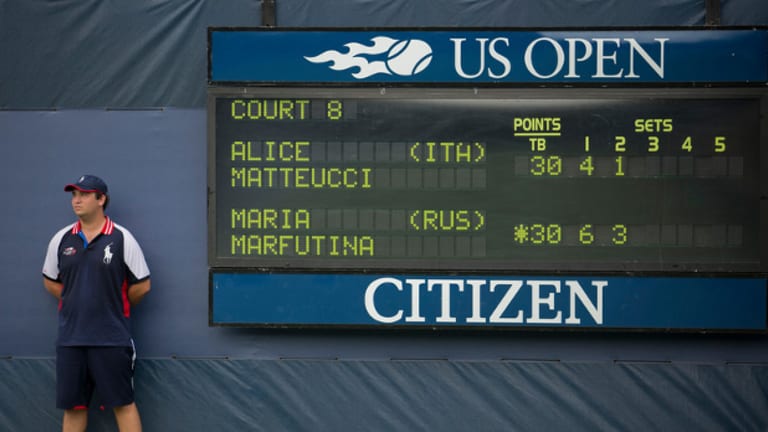

Two weeks later, Max returned to Flushing Meadows for a callback in which he had to run, throw, and catch once again, and also prove that he knows something about the game. One applicant, who claimed that he knew how to keep score but then said that only five points were required to win a tiebreaker, was presumably not hired.