Nadal reached the final of the Australian Open in February—defeating Federer along the way—where he found himself facing Stan Wawrinka, a quality player but one unfamiliar with the championship round of a major. Wawrinka won that match, during which Nadal clearly was affected by some sort of back injury. All credit to Wawrinka; he showed no sign of wavering or choking, and thoroughly earned the win. But it certainly was bad luck for Nadal, and yet another episode in his struggles with competitive fitness.

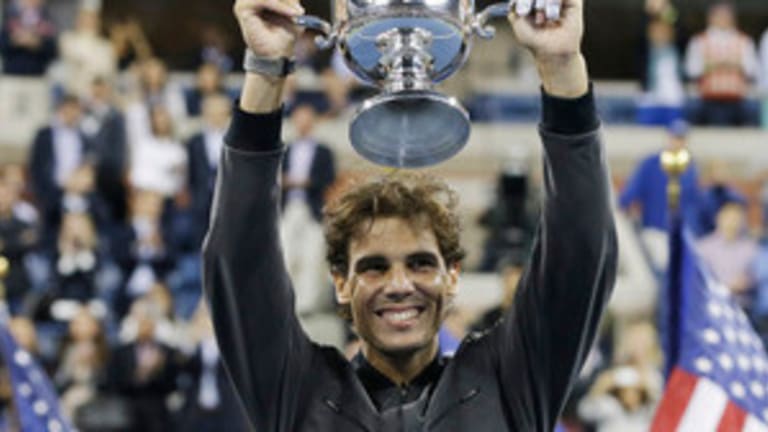

Thereafter, Nadal did what Nadal does best: He won the French Open to bag Grand Slam title No. 14. Despite winning Wimbledon twice, Nadal has been mortal at SW19 of late. This year, he fell victim to a classic Wimbledon upset inflicted by young Aussie prospect and, at the time, world No. 144 Nick Kyrgios (the 19-year-old is up to No. 59 now).

But at least Nadal wasn’t dealing with physical impairments in that match—or he didn’t think he did, until he picked up his sticks again and began to work out for the summer hard-court season. Within days, his right wrist was in a splint, and he called off his commitments to the two hard-court Masters but held out hope to play in New York.

Now, Nadal’s drive to equal or surpass Federer is stalled, and the prospects for its future are uncertain. The King of Clay is 28, so he might be able complete the ultimate mission without having to leave Stade Roland Garros. Andre Agassi was almost 31 when he won Roland Garros in 2001, and if you believe in omens, Andres Gimeno of Spain won Roland Garros in 1972 at the age of 34 years, 10 months, and a day (he remains the oldest French Open champion of the Open era).

The implications of Nadal’s absence for the U.S. Open are profound, and Federer fans are undoubtedly feeling heartened. The Swiss veteran is on fire, having won Cincinnati and placed second in Toronto; he’s the hottest player on the ATP World Tour. And nobody dumps a bucket of cold water over Federer’s flames as consistently and effectively as Nadal. We’ll leave it at that, since the last thing the world needs is another story about how well Nadal’s forehand matches up with the Federer one-handed backhand.

Meanwhile, “What’s wrong with Nole?” stories are sprouting like mushrooms under rotting logs. Although the top-ranked Serb won Wimbledon, he was no factor in the two summer Masters events. Newly married, Djokovic seems to be loving life and feeling pretty mellow. But if Nadal’s abdication at the U.S. Open doesn’t light a fire in his belly, he’s less a warrior that we think.

Andy Murray, down to No. 9 in the rankings, might also find renewed enthusiasm for the last major of the year on the heels of Nadal’s decision. Murray is like a roadside bomb at hard-court events—you never know where or when he’s going to go off. But Nadal has been good at diffusing Murray, winning seven of the last eight matches they’ve played.

Other, less vested players will also have improved chances. Jo-Wilfried Tsonga is rejuvenated, Grigor Dimitrov is an emerging star, and unpredictable talents like Ernests Gulbis and frustrated veterans like David Ferrer will also feel emboldened.

The one thing all the contenders share is the knowledge that, with some luck, they could get to the final, and perhaps even win it, without having to face at least two of the Big Four. And the three members of the Big Four who are playing will know that, with a little luck of their own, they may have to play as few as one match against a Grand Slam peer.