When to walk away: It’s the most difficult decision a great athlete will face, and it’s often one of the few that they get wrong. Muhammad Ali hung on too long in the ring and was pummeled for it. Pete Sampras, after taking months to make up his mind, admitted later that he may have left too soon. Michael Jordan had to retire three times before he finally stopped playing basketball. Martina Navratilova was still playing at age 50.

As another ageless wonder, Jimmy Connors, once said, it’s hard to live without the applause.

For most of 2014, it seemed that New York Yankees shortstop Derek Jeter had managed his disappearing act flawlessly. After hobbling through a series of injuries and playing just 17 games in 2013, the 40-year-old future Hall of Famer had announced that this, his 20th season, would be his last. He said he knew what he wasn’t capable of anymore, and he didn’t want to embarrass himself by hanging on too long. Jeter was right; he had his worst full season since his rookie year in 1995.

At first, everybody seemed to understand. Fans came out in droves to say goodbye to The Captain on his farewell tour. Rival teams honored him as if he were one of their own, and showered him with increasingly over-the-top parting gifts. Whether you loved or loathed the Yankees, you couldn’t deny that Jeter, who was both a charismatic star and an all-business professional, had “done things the right way.”

But as I said at the top, exits aren’t easy, and somewhere along the line Jeter’s began to rub some people the wrong way. His retirement tour was "too much" and a distraction to this team, they said, and his manager Joe Girardi should have benched him. Others began to whisper that Jeter wasn’t all that great in the first place; he has never fared well when measured by baseball’s newfangled Sabermetric stats. That whisper turned to a scream—or at least a very loud whine for attention—when ESPN’s Keith Olbermann launched an all-out, and nonsensically one-sided, attack on Jeter as he was preparing for his final send-off.

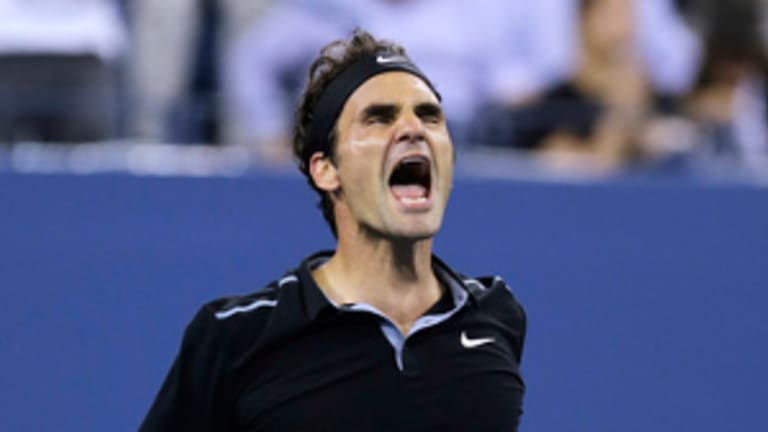

In the end, of course, Jeter made Olbermann and his fellow naysayers look like hopeless killjoys. In his last game at Yankee Stadium, Mr. November won it with a walk-off hit in his final at bat. But the ups and downs of his long goodbye made me wonder if there was anything that tennis’ version of Derek Jeter, Roger Federer, could learn from the experience when he finally decides to hang up his own set of sticks.