Is there a way to be confidently un-confident?

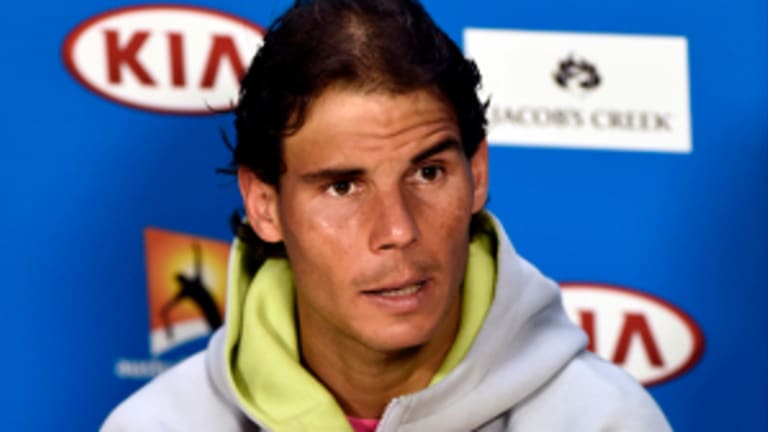

That’s the question hovering over the head of Rafael Nadal as the European clay-court season begins. For most players, it will be a long and leisurely journey to the grand finale in Paris. For the five-time defending French Open champion, it may also be a perilous adventure.

All eyes will be on Nadal in the weeks to come as he struggles with a double-barreled problem. First, the anxiety that has haunted him thus far this year, persistent and well-hidden as a pebble in his shoe. And then there’s Novak Djokovic, the ultra-dedicated player who has just vaulted Nadal on the list of legendary players who have spent the greatest number of weeks ranked No. 1 on the ATP computer.

Small wonder that Nadal has been, well, anxious.

The Spaniard was upset in the fourth round of Wimbledon last year by rising Australian star Nick Kyrgios. A wrist injury kept him off the court for the ensuing three months, and when he returned he developed appendicitis. He floundered through the remainder of 2014, winning a grand total of four matches in the three tournaments he played after Wimbledon.

Nadal seemed primed to make a comeback this year, but he’s taken painful, unexpected losses—the most recent inflicted by Fernando Verdasco in the third round of the Miami Masters. Verdasco had lost 13 consecutive losses to Nadal, dating back to their first meeting in 2005, but now has two consecutive wins over Rafa, both in boldface Masters 1000 events. After that loss, Nadal was sanguine about the state of his game, if not the condition of his nerves.