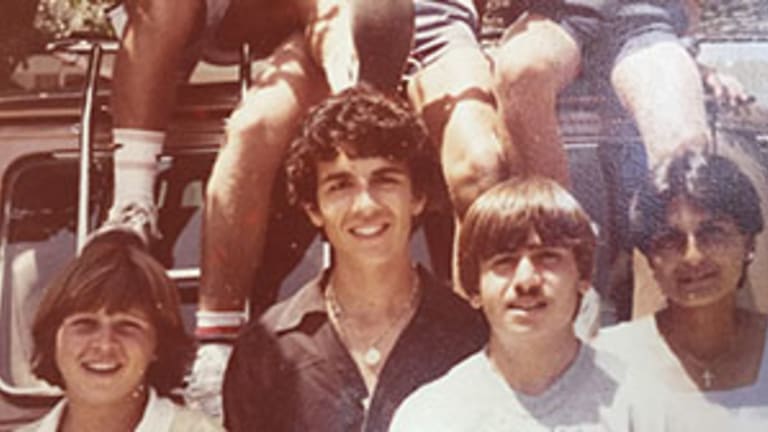

Maureen O'Keefe with Hussein bin Talal, a.k.a. King Hussein (Maureen O'Keefe)

The federation met in a conference room, and Mohammed Asfour, who held considerable authority, addressed me. He explained that they would be very happy if I would be the coach and get a program for the Jordanian children started. When the issue of remuneration came up, he gently told me that it was a poor federation, and they would only be able to pay two Jordanian dinars ($6) per hour for eight hours a week. I paused for about 10 seconds, and then countered that I would be honored to be the national coach. I was confident that I could do a good job, I told the federation members, and said I would give them eight hours a week for free.

I quickly made some decisions. I would teach two hours after school on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, and I would take children ages 10-14. (Lessons would be free.) I made the unpopular decision to only take Jordanian children because I had limited time and only wanted to concentrate on developing Jordanian players. Word got out that Maureen—the king’s tennis coach—was giving free tennis lessons, and I had a good turnout. Within six months I had up to 300 children.

Word got around that I was looking for talented boys to start a team. There was one good player, Hani, who had learned to play in Kuwait. He had slightly unorthodox strokes, but he had plenty of heart and spirit. Even though he was slow in running drills, he was the fastest person I had ever seen on a tennis court.

“Hani, you are so fast on the court!” I once told him. “How do you explain it?”

“Maureen, when I see the ball, I am like a dog going after meat!” he replied.

In Jordan, just about all of my students spoke English well. I never needed to use the little Arabic that I had learned. Even though the tennis program was free and open to all, I only had upper-middle-class participants. Tennis had the stigma of being a foreign sport.

Maher, a muscular boy of 12, arrived at the courts one day.

“Are you the tennis coach?” he asked.

“Yes,” I responded.

“You should take me, because I am good!” he said.

I liked his confidence, and told him he would have to quit the Jordanian swim team if he wanted to be in my serious program. He trusted me and did. Next came Zeyad, a blonde Jordanian. Zeyad had good touch with the ball—he was in. Rami came next. Rami was an intelligent, thin boy who arrived with a glove, and it was fairly difficult to convince him not to use it. Rami brought Nasser, his quiet, intense, athletic friend, and I also had Iyad and Khaldoun to round out this special group of boys.

I worked hard with this group, and yes, I was tough on them. As the boys became better, our goals intensified and I worked them harder. Forehands, backhands, serves, serve returns, volleys, overheads, conditioning, footwork mental strategies: Everything I had I pounded into them.

There were only two obstacles to the boys becoming good players. First, we didn’t have enough courts. When I explained to His Majesty that I needed a place for the kids to practice and play, he immediately financed six courts. The other issue was that there was not enough competition for them in town. They only had each other. I tried to figure out a way to get the boys more competition, and an idea came to me: I could take them to California, where they would have match play at tournaments and clubs.

When I discussed my plan at home, Stan told me there was no way Jordanian parents would let their children go to the U.S. with an American woman. But His Majesty was immediately enthusiastic, and offered to finance the whole venture.

The six boys on that trip were Hani, Zeyad, Iyad, Nasser, Maher and Khaldoun. When we went to Cuesta Park to play our first interclub match, six Asian boys showed up.

“Maureen,” Nasser said, “I thought we were going to play Americans.”

I had to explain that not all Americans are Caucasians. I also, early on, had to help them with idiomatic English. I took them aside and told them that they would have to say “please may I have” instead of “give me.” After that, I made sure that they had all the proper American language manners down. Then there was the rice problem. Very early on the boys started complaining that Americans put cheese on everything. They hated cheese and were starving for rice. Maher, who cooked at home, finally purchased rice at a supermarket to cook and eat in the Stanford dorm.

The trip lasted five weeks, and it was crammed with tennis. The boys played interclub matches against players of their comparable abilities, and we ordered Adidas warm-ups with their names and “Jordan Tennis Federation” on the jackets. They received coaching from various Bay Area professionals, and before coming home I took them to Disneyland in Los Angeles.

The trip to California was an eye-opening, valuable experience for the six boys. Also, Hani’s future was secured when I made a valuable contact for him at a private high school in Menlo Park. Hani went there the following year, and that was his stepping stone to the University of Florida, where he attended and played college tennis.

At the end of 1981, the Arab Championships were coming up in Baghdad. The federation correctly insisted that Abdullah Khalil go as our first singles player. Hani went as the number two, and Zeyad and Nasser filled out the team. As we flew into Iraq on our Royal Jordanian plane, we were told to shut our window shades to avoid being shot at.

Abdullah and Hani won a few rounds, but the Moroccans and Egyptians had fine players, and they were clearly stronger. Our young boys lost early. I visited a souk in Baghdad, where I was escorted by Iraqi women, and posters of Saddam Hussein were everywhere. The Iraqis, who seemed to be loyal to Saddam, were very friendly and very interested in Americans. At every tournament there is usually an evening of entertainment. Towards the end of the tournament, for our entertainment, we were taken to a park which contained dozens of captured Iranian tanks. During the awards ceremony on the final evening, we were constantly asked to stand and salute Iraq and Saddam because another Iranian plane or tank had been captured.

Around this time, Peter and Michael joined us. Peter Abresewski was Polish, and his father had come to Amman for work. Peter was a fine player, and his attendance was an asset for the Jordanian boys. Michael, who was British and Sudanese, was also a good player, and the Jordanians benefited from his level and work ethic. There was also a set of Jordanian girls who were dedicated to improving their games. Carmen, Rasha, Samia, Rana, Sireen and Talia came out regularly, and were making steady progress in my program.